History has virtually forgotten Africa‘s contribution during World War One.

The First World War (WW1) was fought in Africa as well as on the battlefields of Europe and Africa was involved from the beginning right to the very end.

While most of the conflict was in Europe, the warring nations were also imperial powers with colonies around the world. In the late 19th century European countries had laid claim to most of Africa during a process of colonial expansion known as the Scramble for Africa. They promoted the idea of a European civilising mission, bringing the rule of law, order, stability and peace to Africa.

German East Africa was an immediate neighbour to British East Africa, so it was inevitable, following the declaration of war in Europe in July 1914, that the European settlers would take up arms against each other, turning Africa into a theatre of war. Plans for a vast African empire, if they defeated their allies, were desires of both Germany and Britain.

The East African Campaign of WW1 in many ways happened by default although it is regarded by some as the final stage in the Scramble for Africa as an opportunity to fulfill imperial ambitions. When war was declared, those in British East Africa could not envisage how it would change their lives and disbelief was their first reaction.

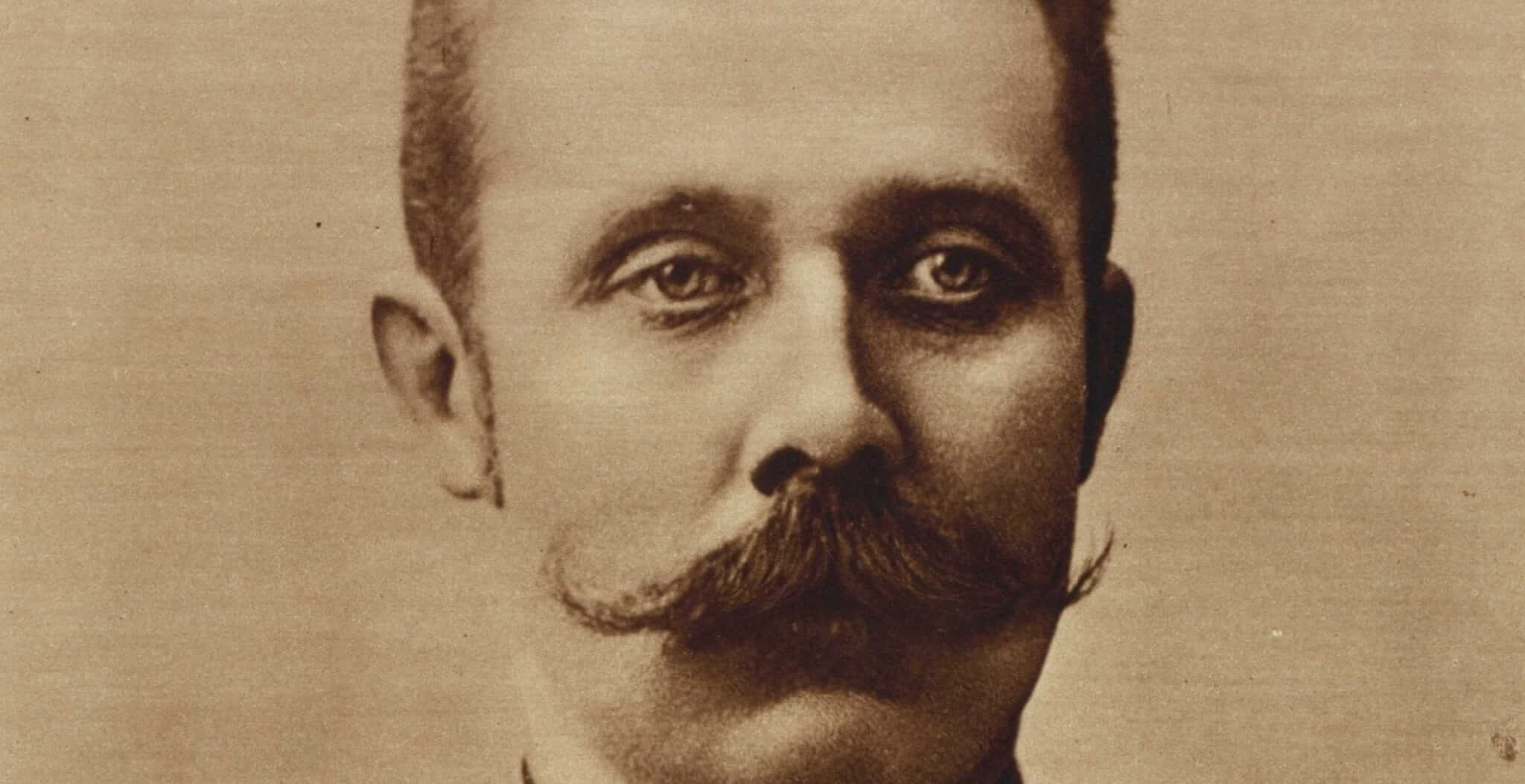

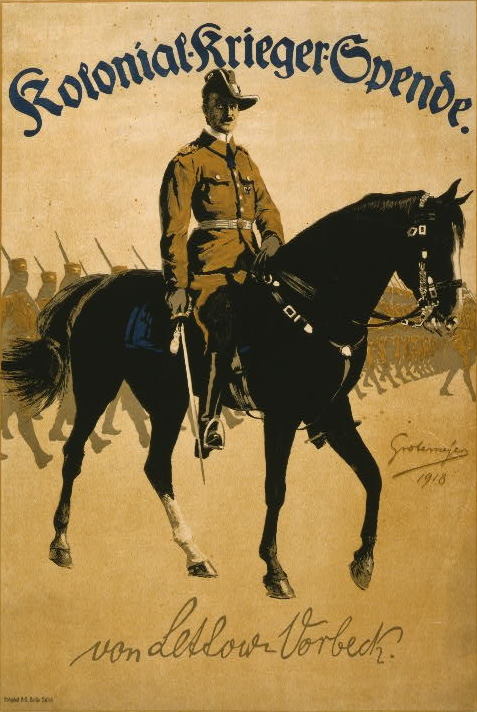

At the outbreak of war, Lieutenant Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck was the commander of the small army in German East Africa. He recognised that he could not win a battle against an army that outnumbered his by ten to one. He therefore ran rings around his enemies inflicting many casualties and avoiding defeat by resorting to guerilla tactics. His strategy was to force Britain and its allies to divert forces and supplies away from the battle in France. He led his enemies on a merry chase across three East African colonies and surrendered several days after Armistice.

Throughout WW1, British Empire soldiers fought against a small German army in East Africa involving thousands of troops and costing the lives of many thousands but the reality is that it is a largely forgotten chapter of world history. Given the enormous scale of mobilisation and casualties and the number of Africans involved in the European war effort of Britain and France, the oversight is bewildering.

Only museum of its kind in East Africa

Occasionally we stumble across a remarkable museum tucked away in a remote country area or small town. The military museum housed in the reception area of the Taita Hills Wildlife Safari Lodge caught me completely by surprise and is one such memorable place. This small engaging museum captures the story of WW1 played out in East Africa and is the only one of its kind in the region.

The Lodge was built like a German fortress to commemorate an epic battle that took place close by. Situated in the area around the modern-day Tsavo National Park, that saw some of the most challenging battles of the war, it is hard to visualize that the area was once a war zone and that the soldiers had to endure appalling conditions, chronic food and medicine shortages, malaria, very little water, extremely hot weather and abundant insects, snakes, lions and other wild animals.

The museum owes its existence mostly to James Willson, an historian and battlefields enthusiast who has been exploring the area for the last four decades, discovering many battle sites and observation posts as well as numerous artifacts belonging to both the German and British combatants, many of which are on loan to the museum. He has mapped the area’s history from the early 1900’s and written a book entitled “Guerrillas of Tsavo: The East African Campaign of the Great War in British East Africa 1914-1916” which details the East African campaign and the extensive part played by the British in shaping the course of Kenya’s history.

A modest exhibition of artifacts and information on the Campaign had previously been displayed at the Lodge, but when the centenary of the end of the First World War approached, a modern, vibrant and commanding exhibition was created for the occasion.

In November 2018 the museum was officially opened by representatives of the former adversaries, the British High Commissioner, His Excellency Mr. Nic Hailey and the German Ambassador to Kenya, Her Excellency Mrs. Annett Gunther. The museum’s intention is to record the military war effort and sacrifices of East African troops in Britain’s East African Campaign.

“This was no side show. It was an important part of the First World War, and the longest campaign in that war” proclaimed historian James Willson.

Entering the museum, a graphic focus panel entitled “A Forgotten Chapter in Kenya’s History” drew me in. The historical journey told with a mixture of pictures, artifacts and detailed panels on the course of the war and its major players was captivating. Some of the artifacts in display cases lining the museum walls are of historical significance including a splendid collection of brass mountain gun shell cases, a breech bolt from a German Mauser rifle and a tailfin from a British 20lb Hales Bomb. Also of significance is a brass plaque that tells the story of HMS Pegasus, a Royal Navy cruiser sunk by the German light cruiser, SMS Konigsberg, during the Battle of Zanzibar. Other exhibits include a German Pickelhaube (spiked helmet) with insignia, spent cartridges, medals, maps, documents, coins and a fine collection of stamps.

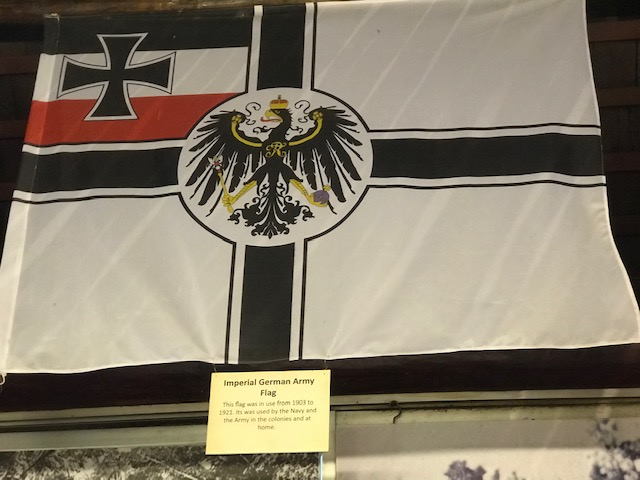

The layout of this small museum is appealing and includes replicas of the Imperial German Army flag, the German East African and British Empire flags. The uniforms worn by both the Schutztruppe and the Kings African Rifle officers are displayed next to photographs of the battlefields as are a soldier’s kit bag, bed roll, sleeping cot and a collection of webbing equipment buckles. While the weight of a soldier’s kit could vary, it was anything but light. The uniforms, equipment and explosives are reminders of a soldier’s daily struggle.

An interesting item found at Crater Fort in Tsavo West National Park, was a rusty Shell Motor Spirit 4-gallon fuel can, converted into a bucket. Some artifacts are more poignant such as a brass horse brush, a rusted sardine can, crude eating utensils, a Roses Lime juice glass bottle (lime juice was used by the British forces as a Vitamin C concentrate to ward off scurvy) and part of a clay Schnapps jar.

An artifact that intrigued me was a 1914 Christmas gift box sent to those serving the British Empire. This container, known as the Princess Mary Gift Fund box, would have contained a mixture of chocolates, cigarettes, lemon drops, writing materials, a photograph of Mary and a signed Christmas card.

An imaginative military diorama, the size of a large table, is in the center of the display room depicting a scene at Mwashoti Fort which was a British hideout post. Suspended from the ceiling above the diorama is a model aircraft of a WW1 fighter biplane, built by university students, commemorating 100 years of powered flight in Kenya since 12 October 1915.

Outside I found another surprise exhibit – a Crossley Motors 20/25 Light Tender chassis that was recovered from a maintenance section of the WW1 Mbuyuni military camp. These vehicles were first used in British East Africa in September 1915 by the Royal Navy Air Service and then by the Royal Navy Flying Corps as staff cars. Another item unearthed at Mbuyuni located near the military field hospital, was the Single Cylinder water cooled motor possibly manufactured by Petter Engineering which is a historic British engine manufacturer.

Also of great interest are the railway sleepers which originated from 400-year-old Australian Jarrah (Eucalyptus maginata) trees, imported by the British East African Company in the late 1890’s for use on the Uganda Railway. A section of railway track is also on display purloined by a German Schutztruppe patrol during one of their frequent forays to blow up sections of the Uganda railway in Kenya. The section on display was used to reinforce the entrance to their command bunker on the summit of Salaita Hill (1914-1916)

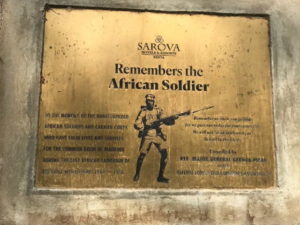

Remembering the African soldiers

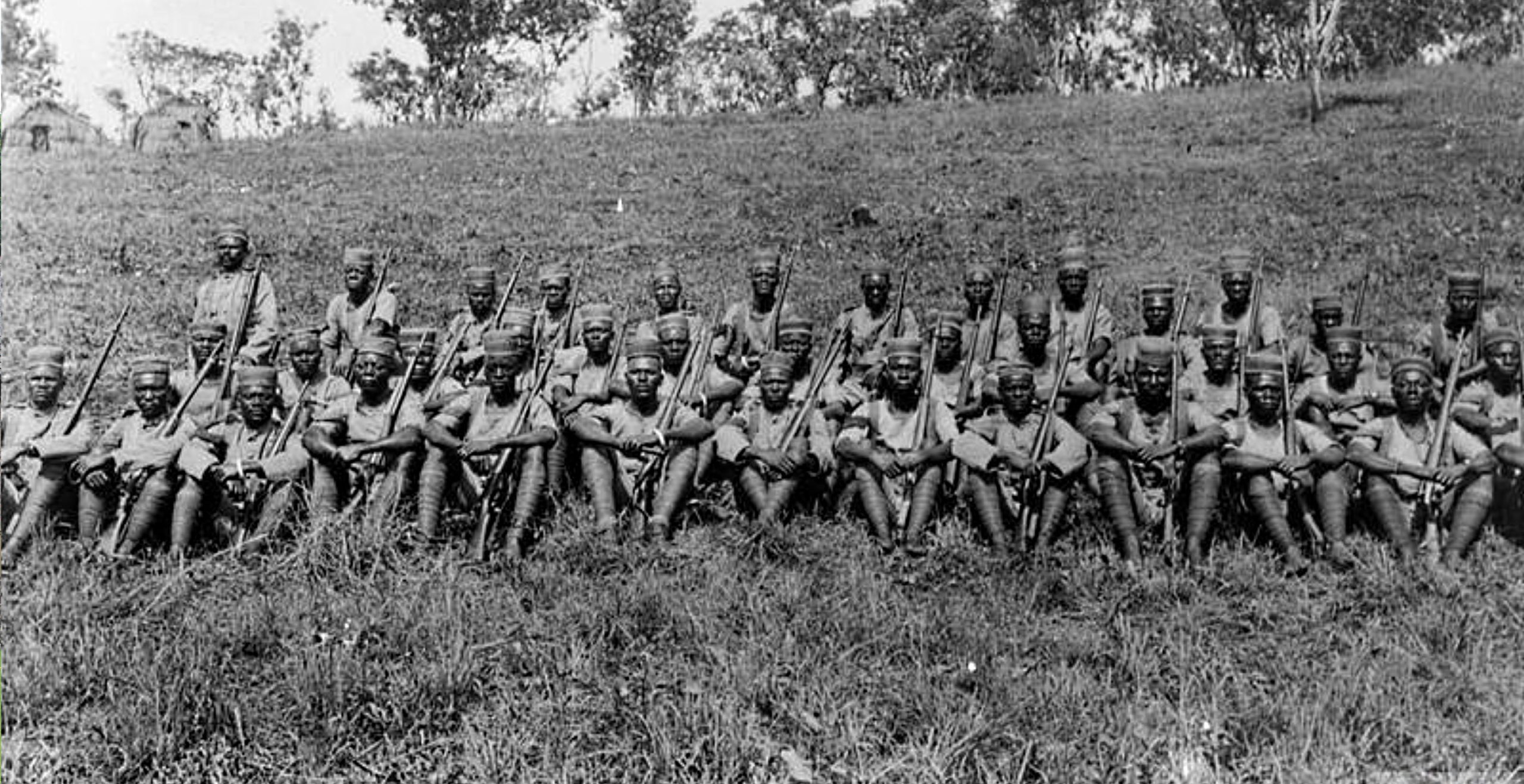

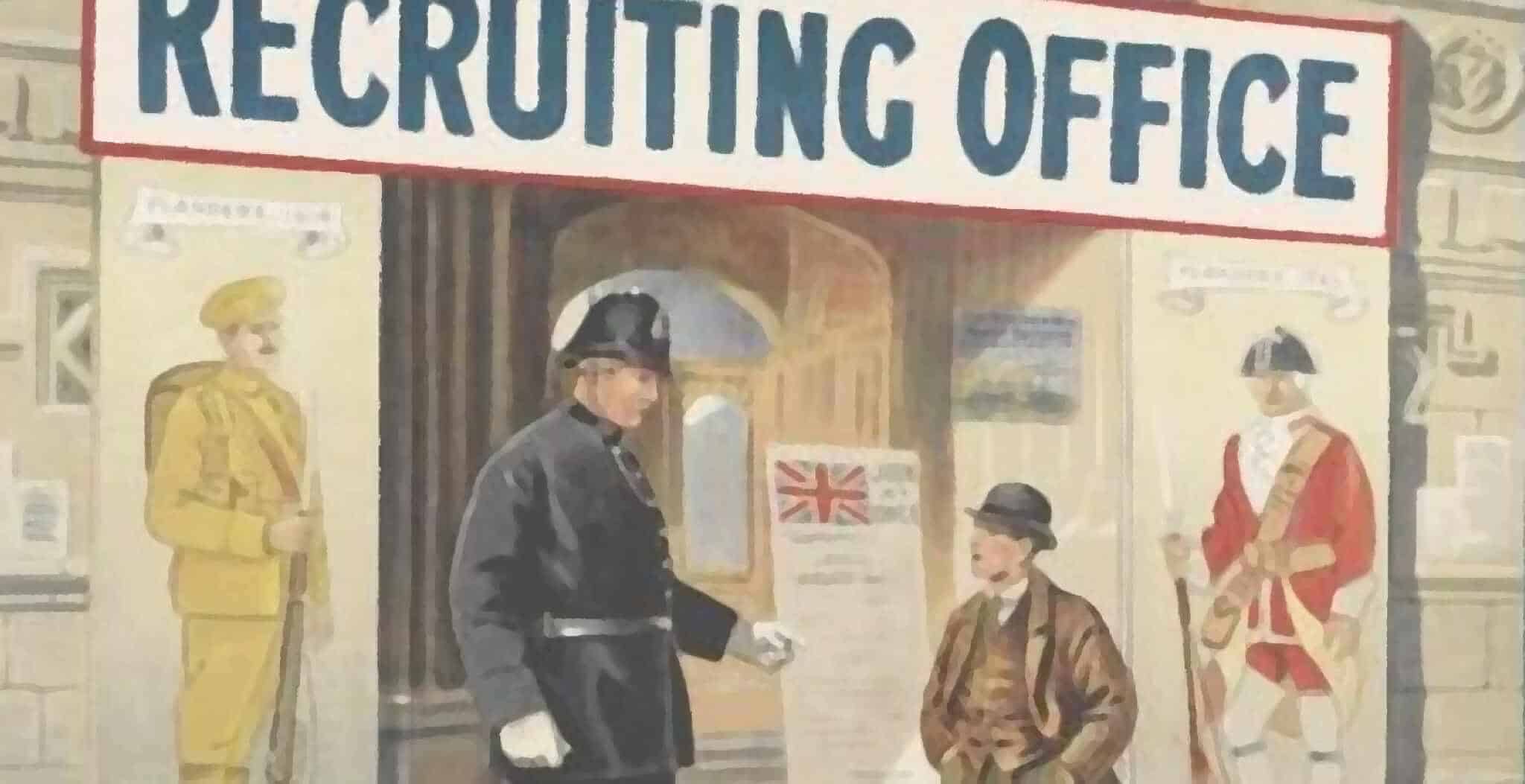

The museum custodian, Willie Mwadilo, is encouraging young Kenyans to learn more about WW1 as an estimated 2 million Africans were pulled into the overall conflict as soldiers and porters in both Europe and Africa. It was not their war, they did not want to be a part of it but were forced to be involved. They were ill equipped and poorly trained but gave vital ground support in carrying ammunition and supplies to front lines under often treacherous conditions. Britain recruited nearly one quarter of the African population in British East Africa as carrier corps or in the Kings African Rifle and by November 1918, the British Army in East Africa was mainly composed of African troops. It is estimated that about 100,000 African carriers and camp followers died on both sides. There are no names, no marked graves or resting places for the African troops.

It was for this reason that a monument has recently been erected to pay tribute to the African soldiers and porters of the Carrier Corps who gave their service and lives. The monument is situated near the almost invisible remains of Mwashoti Fort, remembering the un-named African soldiers and carriers. A brass plaque has also been erected in the garden at the Lodge. The First World War was a turning point in African history with one of the most important legacies being the reordering of the map of Africa.

I could not help but be impressed by this small museum and it is well worth a detour. If you have the time to visit, do consider joining a two-day battlefields patrol that explores the remains of the forts, war cemeteries and battle sites in the area.

Military museums are a perfect place for stepping into the past and learning how it helped to shape our present. For both young and old alike, these historic museums help us all remember how far we have come and appreciate how sacrifices that others made impacted on the opportunities we enjoy today.

Diane McLeish is a freelance writer living on the shores of Lake Naivasha in Kenya. She has travelled extensively to many remote places around the world and especially in sub–Saharan Africa. She is a retired schoolteacher and has written a variety of articles on conservation, history, travel and wildlife.

All museum photographs taken by the author.

Published: 6th October 2021.