On a rock shared with Nottingham Castle, there is a statue. Not of the eponymous Sheriff, but of a 20-year-old fighter ace of the Great War, Albert Ball VC. Albert is with the angels, both literally and metaphorically and looks out over the city of his birth.

Ball was the son of a director of the Austin Motor Company and Lord Mayor of Nottingham. Born in 1896, he worked for an engineering company before war broke out and in 1914 joined the Sherwood Foresters. Speed thrilled him and before long he was seconded to the North Midlands Divisional Cycle Company, zooming around on a motorbike for king and country.

Being earth-bound wasn’t enough for this intense teenager: he used the bike to ride to Hendon Aerodrome in Middlesex for private flying lessons and by the autumn of 1915 the Royal Flying Corps (fore-runner of today’s Royal Air Force) accepted him for their own ground school at Mousehold Heath in Norwich.

Arriving on the Western Front in the spring of 1916, his apprenticeship was spent in slow and steady aeroplanes used for reconnaissance. Ball surprised his colleagues by throwing them around with gusto; his lack of fear was only matched by his curiosity about the mechanics of the machines. Sent to one of the world’s first fighter squadrons in May 1916, there was now a perfect opportunity for him to evolve into an extraordinarily effective combat pilot.

Three men in particular influenced Ball that summer: his squadron commander, the gentle Major Thomas ‘Mother’ Hubbard whose empathy for the young men who were so often flying to their deaths soothed their terrors; the sergeant, Foster, whose ingenious tinkering in squadron workshops gave Ball a flexible machine gun with a wide range of fire, and the equally diminutive Captain Cooper, the Kiwi who stood on tip-toe to fly.

Cooper was killed when his Nieuport Scout, loaded with incendiary rockets, crashed into the ground. Ball’s modus operandi was now to use those same rockets to bring down German kite balloons in the first months of the Battle of the Somme. Other pilots were scared of the unpredictable Nieuports; Ball used them with reckless abandon to great effect.

As his list of victories grew, he gained a reputation for being difficult. He asked for a rest after a particularly hot period of fighting – a request that offended Brigadier General Higgins, who sent him back to reconnaissance. For a pilot so used to only considering his own mortal danger, it was a heavy blow as the planes he now flew also carried observers. Ball’s family, and Hubbard his commander, knew of the stress that had so sapped his energies, but Higgins could not make a special case of him.

So he packed up the hut he had built on No.11’s airfield and left his vegetable garden to be tended by a local. Squadron mates had got used to him playing his violin outside in the evening, lit only by a flare. He was something of an enigma to them; not a clubbable man and one happier sleeping in his hut than in a comfortable billet. In the air the reserve disappeared and his habit of suddenly appearing underneath an enemy aircraft earned him the nickname of the ‘Berserker’, after the Viking warriors who fought in a trance.

Posted from No.11 to No.60 Squadron, Ball was now flying the most effective planes that the RFC had and by the autumn of 1916 he had won the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Military Cross. Word was leaking back to Britain of this prodigy of the skies. Despite the Flying Corps’ insistence on the value of a team effort, Ball’s bravery was earning him hero status.

A posting back to Blighty pleased the newspapers; there were dinners with Lloyd George and a visit to the palace to pick up his MC; but life as a public figure unnerved him and passing on his skills as a fighter pilot only made him crave to be back in action again. In Feb 1917 he joined No.56 Squadron, a new unit, handpicked and made up of the best pilots in the Flying Corps.

They were not yet ready for the front, and his time at London Colney in Hertfordshire brought him a tender love affair with a local girl, who he literally swept off her feet when he took her up in an Avro aircraft. Ball’s romances gained as many legends as his flying; this one was conducted with an intensity unsurprising for a young man about to return to combat. He gave her an identity bracelet and asked her to marry him.

On a snowy morning in April 1917, No.56 Squadron left for France and the next three months of Ball’s flying cemented his reputation as one of the outstanding aces of the war. In the air his ‘lone wolf’ method of aggression and degree of personal courage was extraordinary, but even while its results were feted, some began to question the long-term wisdom of such a single-handed strategy at a time when dogfights now involved dozens of aircraft.

So many men were being lost to superior German pilots in superior machines that ‘Bloody April’ came to symbolise yet another unbelievably terrible episode in a war that above all others, as folk and cultural memory still insists, seemed to have spawned them with the most horrifying efficiency.

Even General Trenchard, the man in charge of the RFC, saw the signs that Ball’s reserves of courage and energy were running dangerously low but failed to order him home; and in any case his offer of a rest was turned down. A few days before the end, a wild-eyed Ball reported a near miss to the squadron office. The German had blinked first, but Ball was distraught and could barely get his words out.

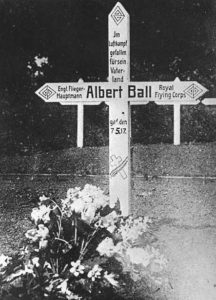

The RFC excelled in euphemisms; ‘the breeze vertical’ was a black-humoured description of failing courage. In the end it was Ball’s machine, rather than his nerve, that failed him. In failing light on 7th May 1917, his aircraft was spotted flying upside down out of a cloud, crashing near the village of Annouellin. He was still alive when a local girl dragged him from the wreckage, but his back and one leg were broken, and he died within minutes.

Time had always been running out for Albert Ball; his spectacular solo successes could never have been sustained in an air war that twisted and turned as much as its machines. But his chutzpah was a perfect illustration of the spirit of the Royal Flying Corps, bloodied but unbowed.

Pilots in the Second World War were in still in thrall to the legend of this diminutive lad whose forty-odd victories inspired a generation.

‘He must fall. Remember Ball!’

Jill Bush is a freelance author and researcher living in East Sussex. Her book ‘Lionel Morris and the Red Baron’ is published by Pen and Sword Books. www.jillbushwrites.com