During World War Two the Soviet Union was viewed by the democracies as the ‘lesser evil’ when compared to Nazi Germany. However in the 1930’s, this was certainly not always the case, especially in Britain. The British establishment – centre-right – and the more extreme right-wing parties saw Hitler’s Germany not just as a strong nation which could cripple communism once and for all, but also as a country they could possibly ally with, or at least encourage to attack the home of communism with some tacit support.

Britain’s longstanding ally, France, did not share this view and saw an aggressive Germany on her border as a major threat and Russia as an ally. Therefore the Parisian government sought a similar relationship with their eastern European ally as they had done before the First World War. With the British dithering over a formal alliance against Hitler, the French sought solace in a treaty with the Soviet Union, signed in February 1936 just three years after Hitler took power.

Although the British kept on excellent terms with the French, they were extremely sceptical about fully supporting a country whose politics in the 1930’s were at best shambolic. French governments could last a few hours and rarely did one manage to rule for more than ten months. The British right viewed the French military as backward, with their tactics aimed at fighting a war they almost lost nearly twenty years ago. They saw the real enemies of Britain and her empire as the USSR and Japan, and with America constantly purveying a policy of isolation, a number of British politicians and influential public figures saw a strong, militaristic Germany as a potential ally to curb the communist threat to the Empire.

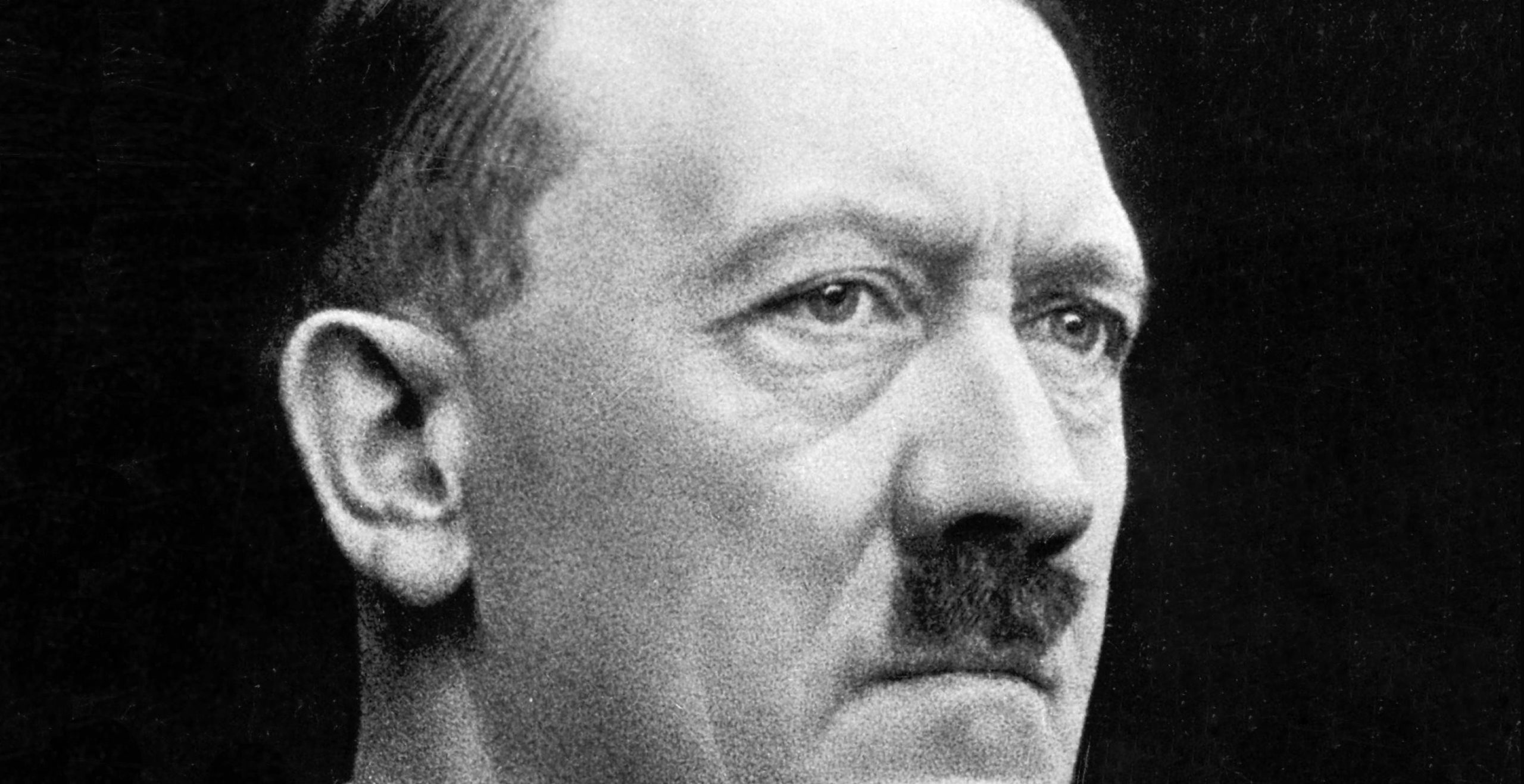

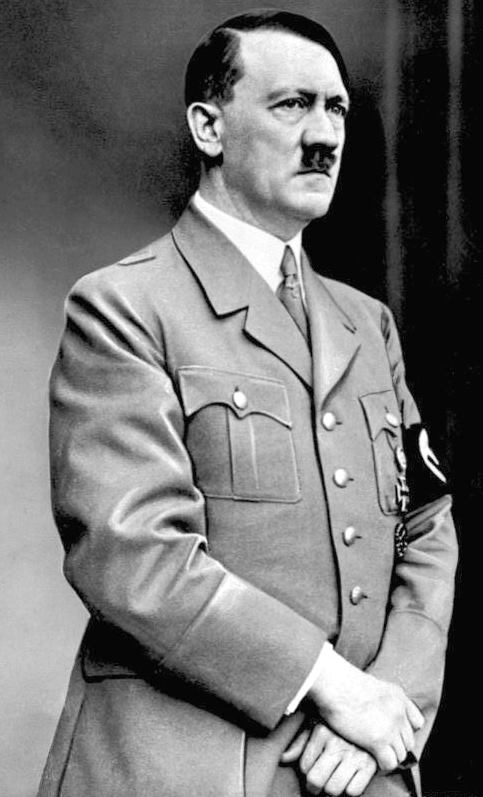

In March 1935 a lunch was organised in the British Embassy in Berlin. Hitler was invited and he met the Foreign Minister, Sir John Simon and the man who was to be his successor, Anthony Eden who at the time had the title ‘Minister without Portfolio for League of Nations Affairs’. It was a highly successful meeting, with Hitler and Eden actually discussing the Battle of Ypres in which they both took part and in fact were roughly opposite each other in their respective trenches. Both men felt that they could work together after their preliminary talks and Hitler was pleased to hear that Eden was made Foreign Secretary a few months later.

In June the same year the Anglo-German Naval Agreement was signed. This not only broke the conditions of the Treaty of Versailles and was negotiated by the British without any consultation with either the French or the Italians, but was viewed by the Nazis as Britain’s first move to a formal alliance against Russia and France. During the war the British claimed it was a part of their appeasement policy, but many German officials claimed that there were clauses that were anti-Soviet and that Britain would come to the aid of Germany, if she was attacked by the communist state.

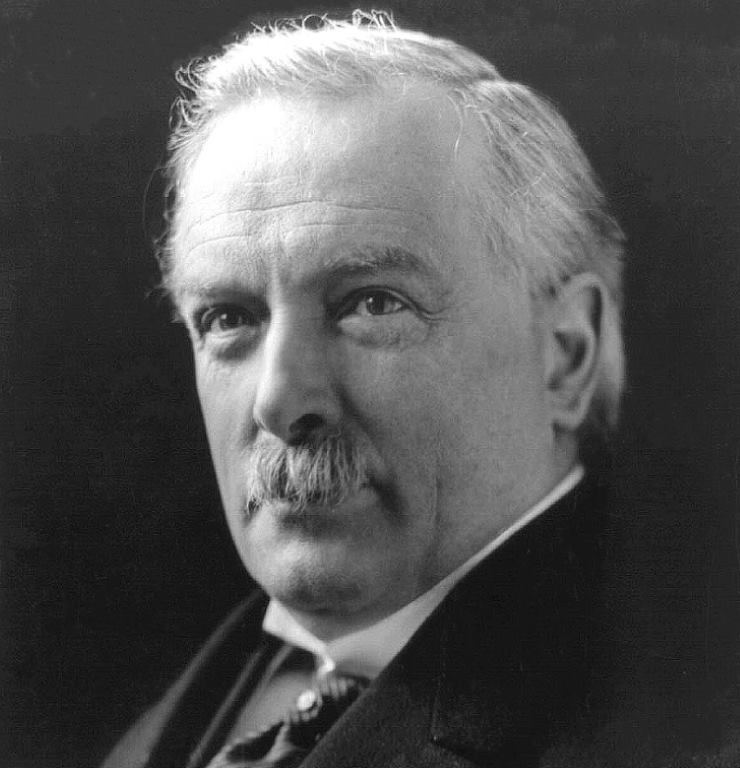

Friendly relations continued between the two countries the next year with former prime minister David Lloyd George visiting the Fuhrer at his Bavarian retreat in September 1936. Lloyd George was very impressed with the very pro-English Hitler. He claimed that, “Germany does not want war and she is afraid of an attack by Russia”, something that many British politicians were also concerned about. He practically apologised for the First World War and said, “There is a profound desire that the tragic circumstances of 1914 should never be repeated”.

This was music to Hitler’s ears. More than anything else he dreamed of an alliance with Saxon England. A nation, he believed, that was made up of and run by people of “excellent Germanic stock”. He was not too sure about the Celtic races that made up the rest of Britain though, and always referred to the UK as “England”. Hitler proclaimed that, “the English nation will have to be considered the most valuable ally in the world”. He added, “England was a natural ally for Germany and an enemy of France”, plus the latter’s communist friends in Russia, no doubt. Relations became even more cordial with the Fuhrer, referring to ‘Mein Kampf’ and other publications of his, when he asserted that the English are, “our brothers, why fight our brothers?”. Then Lloyd George came out with a quite remarkable comment. Although everyone was aware of Hitler’s antisemitism from his autobiography and in the 1930’s the Nazis’ treatment of the Jews was not as severe as it would be in the next decade, the ex-British premier reminded his audience that, “we must not forget the pogroms in Russia and in other European countries”. It was as if he was saying that maltreatment of the Jews happens, and has happened in communist Russia, so why attack Germany for doing the same?

Tacit British support for Germany continued under the veil of appeasement. During the Spanish Civil War the British did very little to assist the legal, Republican government. In fact British military intelligence in Gibraltar passed on messages they ‘overheard’ from the Republican side and they did all in their power to stop British citizens joining the International Brigade, a division of the Spanish Republican army made up of anti-fascists from all over Europe. Anthony Eden told the French foreign minister, Leon Blum that, “England preferred a Rebel victory to a Republican victory”. In other words Britain wanted Franco and his fascists to take control of Spain rather than see it fall into the hands of anarchists and communists who would be controlled by Moscow.

Franco knew this and in 1944 and 1945 requested that Spain and Britain form an alliance against the Soviet Union. These were the bleatings of a man who knew his old fascist friends were on the way out and he wanted a settlement with the victors to secure his own position. However, by this time there was very little chance of the British alienating Russia, especially with the pro-Stalin Americans taking the lead on the western front and not Britain.

So after looking at how friendly the British and German governments were in the 1930’s, why was there no Anglo-Nazi Pact?

With only the right in British politics even suggesting such a policy, there was very little chance that the rest of the country would allow any congenial relations with a fascist dictator who was already overrunning neighbouring countries and persecuting people because of their race and creed. Although Oswald Moseley’s British Union of Fascists had strong support in many of the English towns and cities, especially in the north, the vast majority of the Britons, especially in the Celtic countries, valued their liberal democracy and freedom. Most could recall the hatred they had felt for a foe that had massacred their countrymen on the fields of Flanders and elsewhere twenty years ago.

There was also one man who inadvertently undermined everything that Hitler wanted from an Anglo-German alliance. It was his close friend and confidant from the early days of the Nazi party, Joachim von Ribbentrop. The Fuhrer sent him as German Ambassador to Britain in August, 1936. He single-handedly destroyed any hope of a rapprochement between the two countries in a number of ways. He insisted on giving an outrageous fascist salute when meeting King George VI and seemed astonished that the king did not reply in the same manner. At most meetings with British ministers he argued that Germany must be given back the colonies she lost after the First World War. Fortunately for the British ministers there were not many meetings as Ribbentrop often found it necessary to fly back to Berlin to interfere with what his fellow Nazis were doing there because, as he kept telling everyone, including Hitler, “I know best!”.

However, it was his attitude that most offended the British people. Even his personal secretary, Reinhard Spitzy observed that, “he behaved very stupidly and very pompously and the British don’t like pompous people”. He added that Ribbentrop was, “an insufferable man to work for”. While Spitzy encouraged closer Anglo-German relations and he even recalled Henry VIII’s wish that the English navy should control the seas while the 16th century German emperor, Charles V’s army should control the European mainland, Ribbentrop would be arguing with the governors at Westminster School on how badly his son was being taught and treated. And just like the Tudor king’s relationship with the Holy Roman Emperor broke down over the king’s divorce from the emperor’s aunt, the inter-war friendliness between Britain and Germany broke down to the extent that on 2nd January 1938 Ribbentrop reported back to Hitler that, “England is our most dangerous enemy”.

Are there any realistic claims to there ever being a chance of an Anglo-Nazi Pact?

Adolf Hitler believed that there was a very good chance of such an alliance in the mid-1930’s. So much so that he felt confident enough to openly assist Franco and the fascists during the Spanish Civil War and he believed that Britain would not interfere, or in fact help him, when he untangled the bonds of the Treaty of Versailles that restricted the German military and territory. British appeasement, if that what it was, just added to his belief. All this therefore led to the Second World War.

Another who believed that the British were on the side of Hitler was Josef Stalin. He and the politburo in Moscow certainly believed that an alliance between the two powers was on the cards in the 1930’s. He claimed this even during the war, especially when as late as 1940 Prime Minister Winston Churchill suggested that Britain should defend Finland against the advancing Red Army. For his entire life Stalin never trusted the British and argued that a NATO containing the United Kingdom and the post-war West Germany was an alliance specifically set up as an aggressive pact against the Soviet Union. This is something that Russian premier Vladimir Putin, even in the twenty-first century still believes is happening and is one reason why he seeks to rebuild a buffer zone, starting with the Crimea and parts of the eastern Ukraine, to keep an aggressive Germany and Britain out of Russia.

By Graham Hughes, history graduate (BA) from St David’s University, Lampeter and presently head of history at Danes Hill Preparatory School, a leading British prep school.