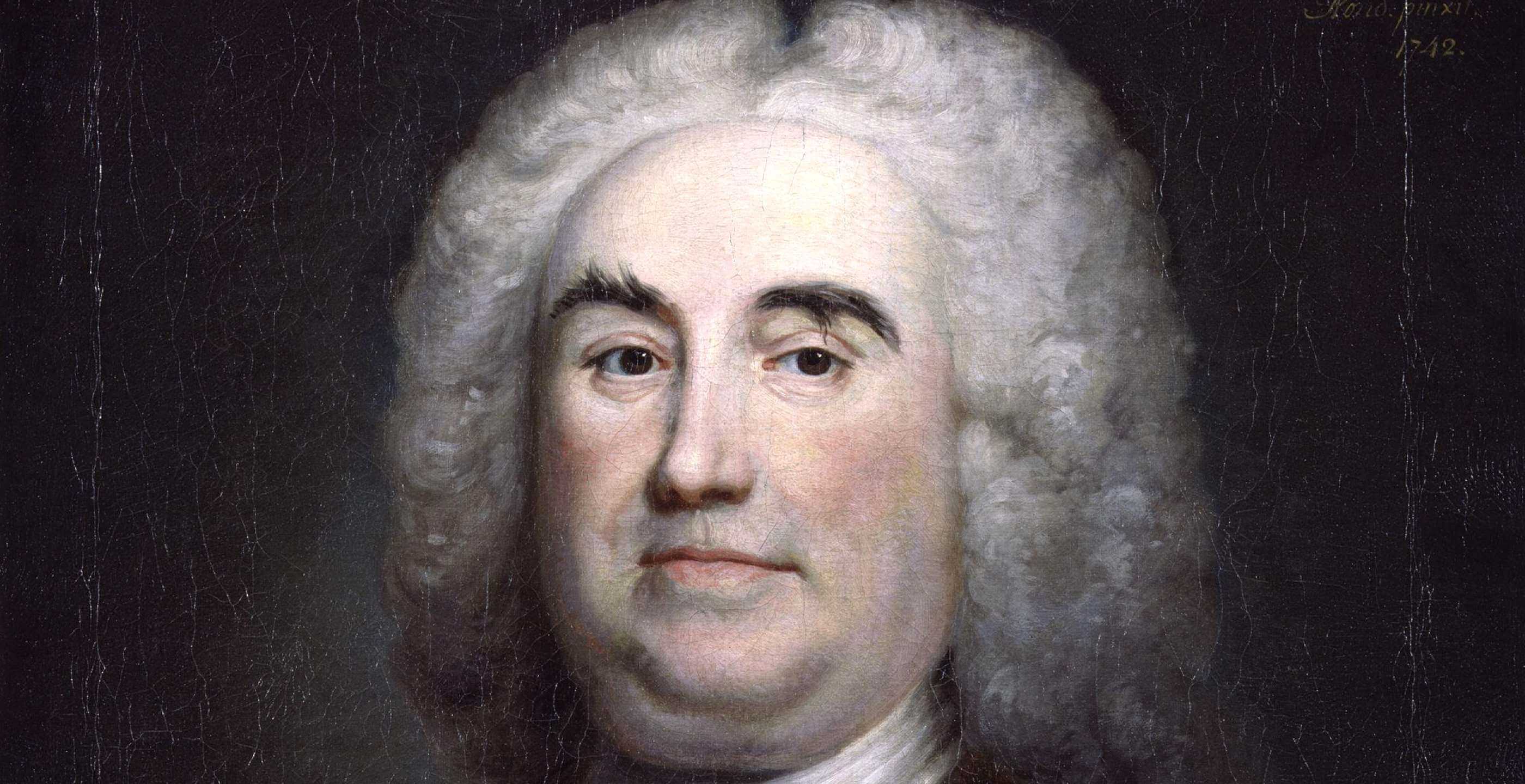

In 1737, Captain Robert Jenkins presented his severed ear to Parliament claiming a Spanish official had cut it off. This incident provided Britain, eager for a reason to declare war, with the pretext they needed. Fuelled by merchants and public anger, Britain declared war on Spain in 1739, aiming to expand its empire and business opportunities.

This campaign was not led by Francis Drake or Walter Raleigh, but instead by Edward Vernon. Vice-Admiral Vernon, a veteran of the Spanish War of Succession, was renowned for his strong and decisive leadership and was a vocal supporter of a war with Spain.

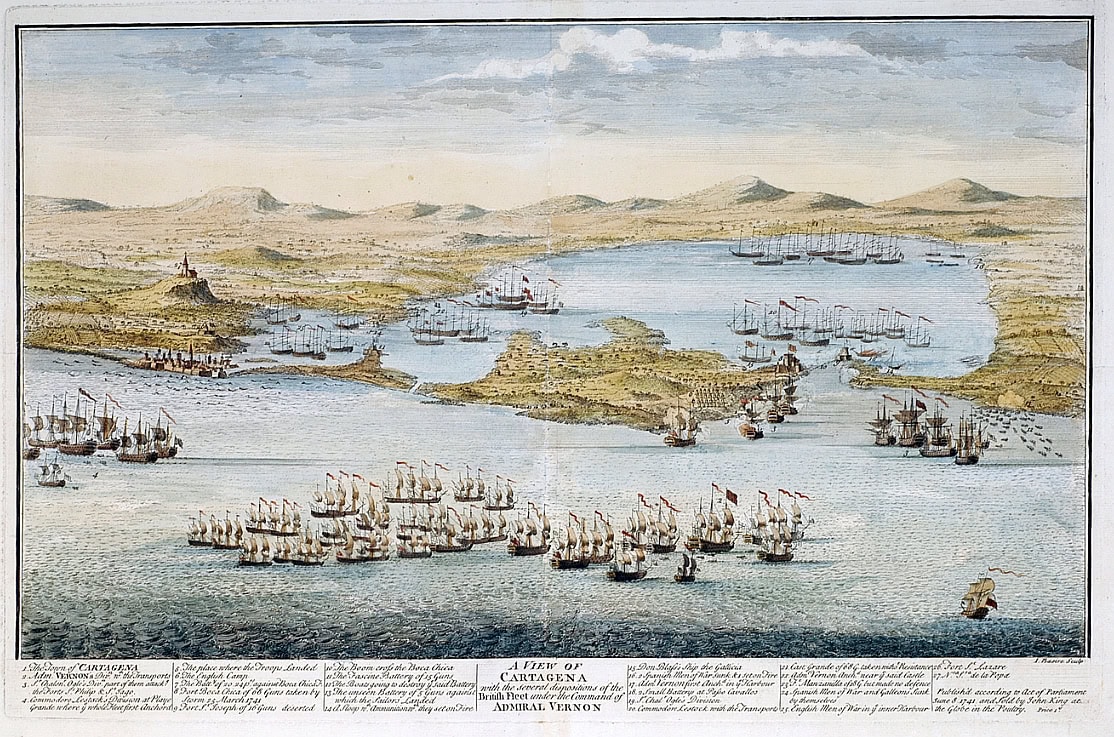

The British assembled a formidable fleet, with over 180 ships and 30,000 men, comprising soldiers, sailors, and slaves in what would be the largest amphibious assault force until D-Day 230 years later.

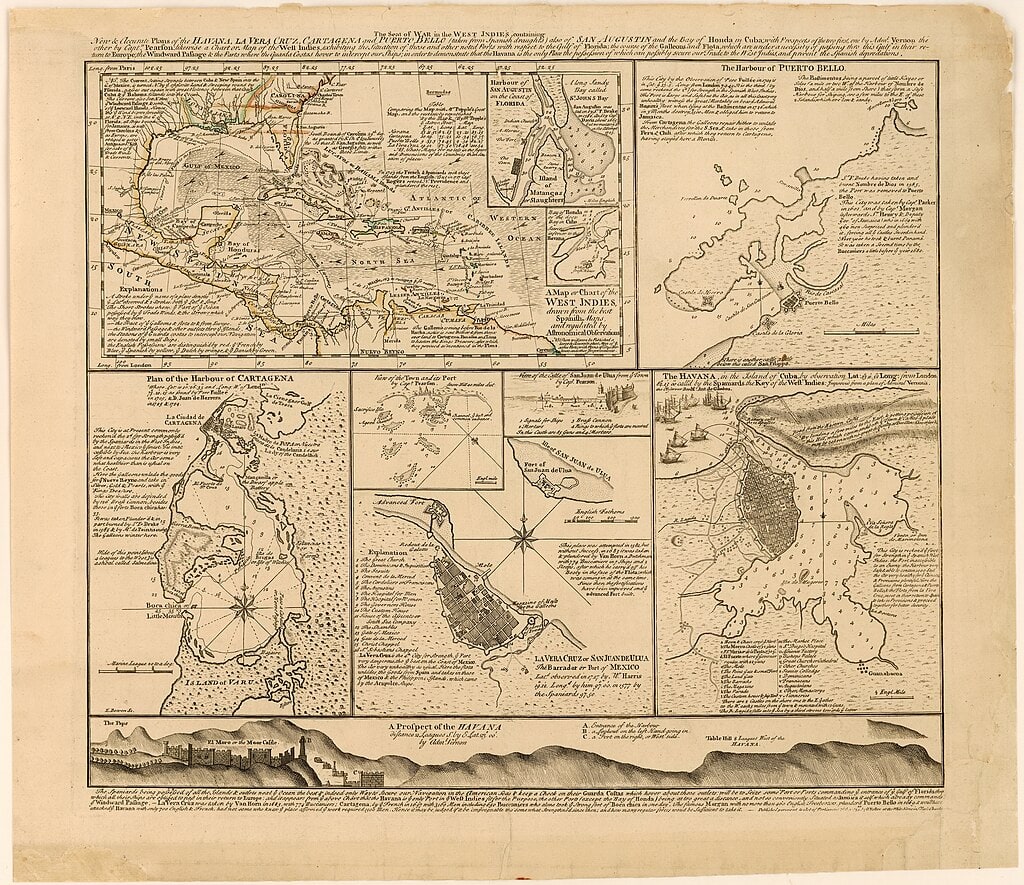

The Admiralty planned to capture all four key Spanish ports in the Caribbean basin. If Portobello, Havanna, Vera Cruze and Cartagena were all taken “the Spanish will have lost everything.”

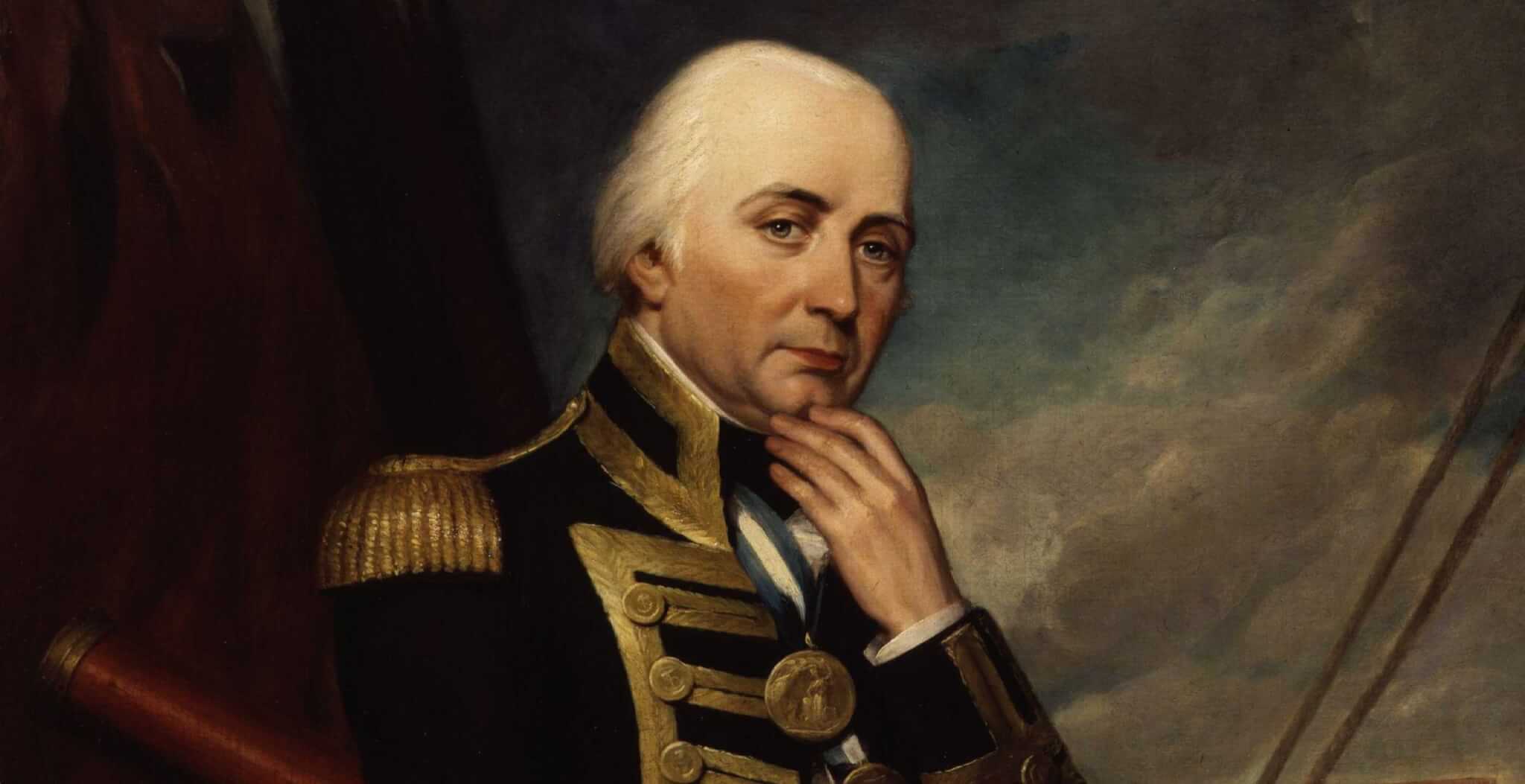

Command of the invasion fleet was given to Lord Charles Cathcart, but he died quickly on the journey from England throwing the original plan to attack Havana into uncertainty.

Upon reaching Jamaica, the fleet was reinforced with ships and soldiers from Britain’s North American colonies, bringing a quarter of the Royal Navy to Kingston. At a council of war, the officers debated their next move. While some favoured attacking Havana, Vernon proposed an alternative: sailing south to attack Cartagena. He argued that Cartagena would be easier to assault and would allow for a quicker return to England.

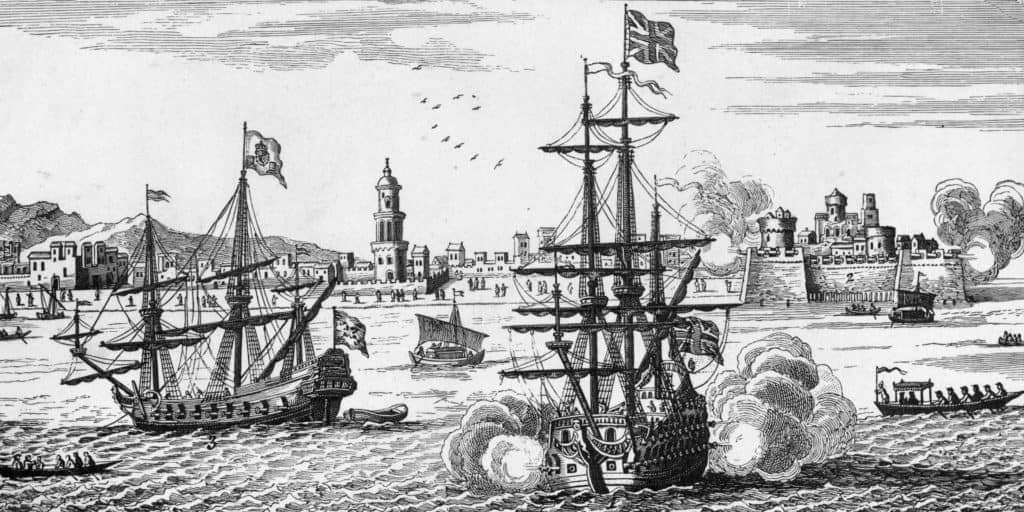

Cartagena was a critical port for the Spanish and was protected by 11km of walls with over 160 cannons. Overlooking the city stood the imposing Castillo San Felipe, considered one of the strongest fortifications in the world and the largest military complex built by the Spanish in the Americas. The city’s defence was commanded by the one-eye, one-hand, one-legged Admiral Blas de Lezo.

Vernon’s assault started in March and unfolded over several weeks. Before the battle began the British had lost so many to disease that one-third of the soldiers were being used to crew ships.

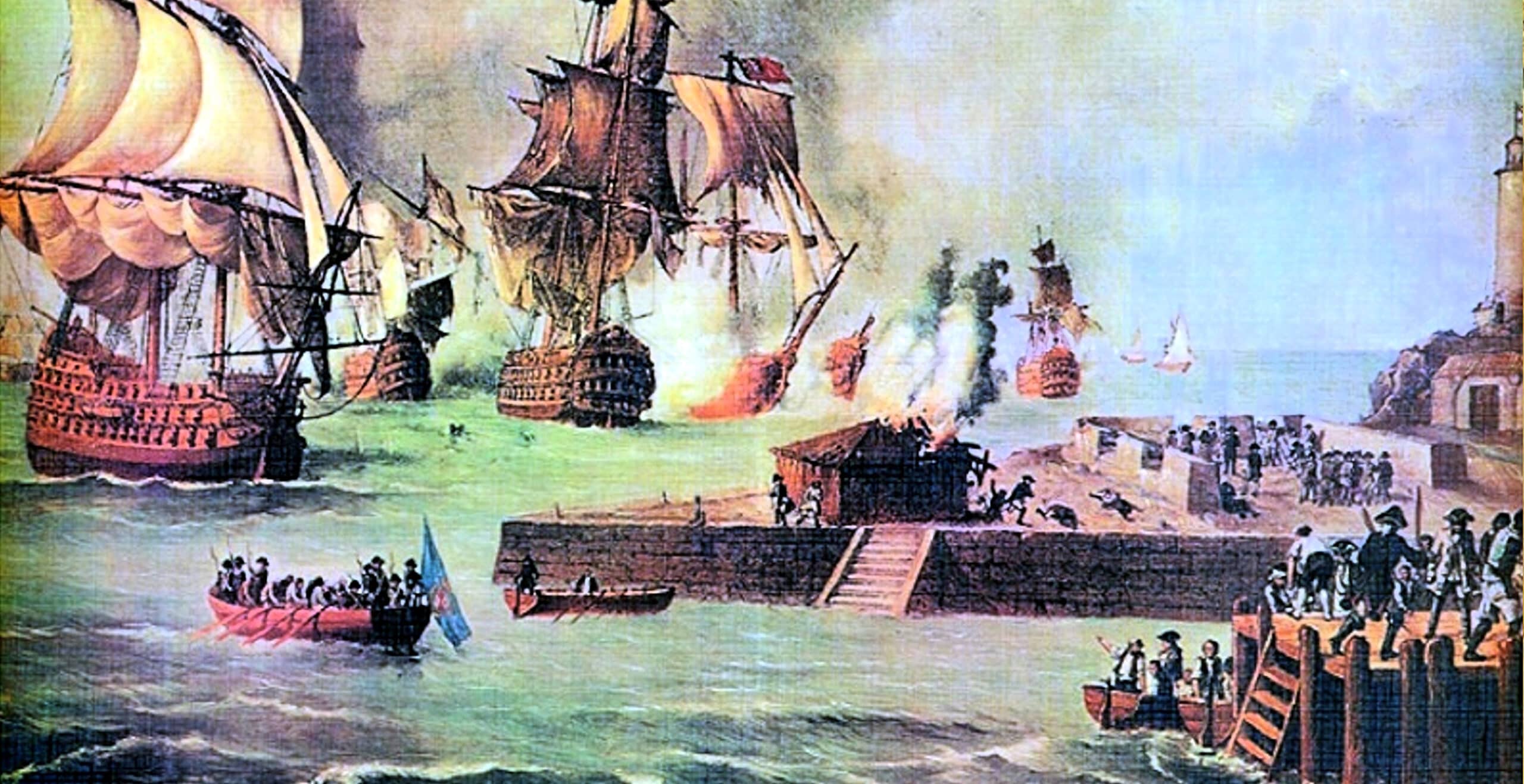

The British strategy was simple; bombard the city’s defences whilst landing troops to seize strategic positions. However, the British faced numerous obstacles. The complex network of Spanish fortifications and the effective leadership by Blas de Lezo posed significant challenges.

The main entrance to the bay was heavily protected by fortifications, the largest of which, the Fort of San Luis, had 49 cannons. The 6 Spanish warships further reinforced the defences.

It took a week of naval bombardment to silence the smaller forts. With these silenced, Vernon could turn his attention to the fort of San Luis. The British disembarked their ground forces: two infantry regiments, six regiments of marines, 300 American soldiers, and 20 pieces of cannon were now camped outside of the fort. The British guns began shelling the San Luis relentlessly. After another week, a breach in the walls was opened and the fort fell quickly.

The operation against San Luis cost the British army 120 men, a further 250 died from the diseases, and 600 were hospitalised with illness. Naval battles with Spanish ships and the fort killed hundreds of sailors. Vernon was making costly progress. An assault on the city was imminent.

Vernon was so sure of his triumph that he sent word back to England saying victory was inevitable. People were ecstatic, with medals, coins, trinkets and songs flooding the streets in anticipation of Vernon’s victory. Vernon was a Hero.

With the fort of San Luis under British control, Vernon could sail his ships into the city’s harbour.

However, things were not smooth sailing. Since the death of Lord Cathcart, Vernon and General Thomas Wentworth had been in overall control.

Wentworth was not second in line to command; that was General Spotswood. He had also died of disease and thus command fell to Wentworth. Wentworth had no previous experience in commanding men in battle.

Vernon and Wentworth did not get along, possibly due to Vernon’s view of himself as the more experienced commander and Wentworth’s proud aristocratic background. The pairs’ conflict, along with rampant disease, would severely hinder the British.

Onboard HMS Princess Caroline a war council was held to discuss the next moves. It was decided that the remaining land forces should cut the Spanish city off by land. If the fortress of San Felipe could be taken, the city of Cartagena would be blasted into submission from the fort’s high walls.

Admiral Blas de Lezo knew his forces could not stand up to the British in a head-on fight. The Spanish commander instead opted to buy himself time, slowly pulling his soldiers back to defend the main fort. Blas also knew that tropical diseases would wreak more havoc on the English than his men.

Meanwhile, Vernon goaded Wentworth into an ill-fated assault on the castle. An experienced commander would have found it a challenge. For Wentworth, the task was impossible. The assault was made even harder by Vernon’s refusal to provide cannon support. He instead made false excuses that the harbour was too shallow for his ships to mauver. To add to the already dire situation, the only British engineer was killed during the assault on the fort of San Luis.

Without artillery support, Wentworth decided to storm the unbreeched fort at night, preventing the city’s guns from targeting the British. Night assaults in the 18th century were risky, especially when 2,500 men were guided by two Spanish deserters. Unsurprisingly, the British were led to a steep approach toward a heavily defended section of the fort.

Undeterred, the British attacked, but the situation rapidly worsened. The grenadiers faced heavy musket fire, and Colonel Grant, leading two regiments at the south wall, was killed, leaving his troops leaderless and confused. The ladders were too short, and as the sun rose, the city’s guns targeted the British. A column of Spanish soldiers then advanced from Cartagena, threatening to cut off the British from their ships. With 600 British soldiers killed in the assault and disaster looming, Wentworth ordered a retreat.

After 67 days of fighting, Vernon finally decided to call off the siege of Cartagena. The aftermath was devastating.

Admiral Vernon and General Wentworth were recalled to England in September 1742 in disgrace. 15,000 British soldiers and sailors were killed (many due to disease) 1,500 guns, and 50 ships were lost or damaged. Out of the 3,600 colonial soldiers, only 300 returned home. By the end of the campaign, 90% of the army had died from combat or sickness.

The Spanish, in comparison, lost 800 men and 6 ships. Blas de Lezo cemented himself as one of the greatest naval strategists in history.

The failed assault caused the collapse of Robert Warpole’s government and weakened the Royal Navy. The disaster forced King George II to remove his military guarantee from Austria, paving the way for the War of Austrian Succession.

By 1742, Britain was in uproar, thousands had died, the Spanish position in the Americas was stronger than ever and war was on the horizon.

By Max Rockliffe. I hold an MA in History from Queen’s University Belfast. My research focused on Early Modern popular culture in England, specifically on the medium of English broadside ballads. In my MA thesis, I explored the connection between ballads and popular perceptions of the maritime world. Currently, I’m backpacking through Latin America, learning about the rich histories and cultures of the continent.

Published: 22nd October 2024.