On 24th January 1900 during the Second Boer War, in an area about the size of London’s Trafalgar Square, the flat top of a South African mountain became the killing field for hundreds of infantrymen from three Lancashire regiments. The carnage on the peak known as Spion Kop (spelt Spioenkop in Afrikaans, meaning Spy Hill) caused newspaper correspondents to describe it ”An Acre of Massacre.”

After receiving reinforcements until his army in Natal comprised 19,000 infantry, 3,000 cavalry and 60 heavy guns, General Sir Redvers Buller abandoned his plan to lift the siege of Ladysmith by fording the Tugela River at Colenso and instead moved 25 miles upstream to cross the river using pontoon bridges.

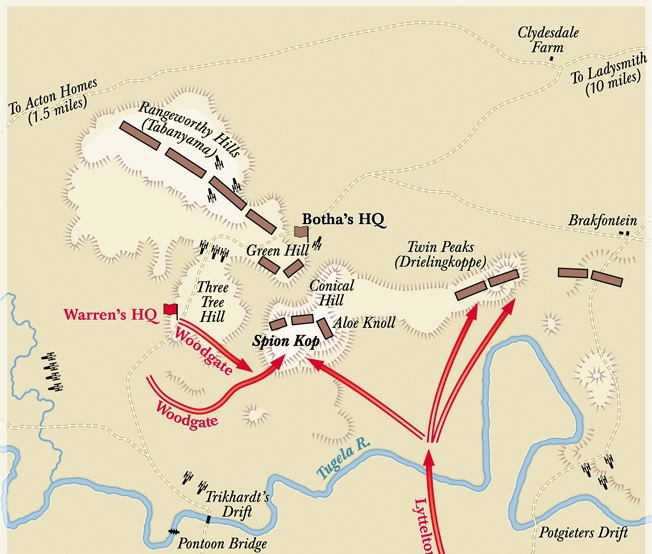

Once they were over the Tugela river, the cavalry galloped forward to turn the Boer right flank while 16,000 British troops camped under the steep slopes of Spion Kop.

Winston Churchill, reporting for “The Morning Post,” believed that if the cavalry continued their attack they could have broken through the Boer lines and been followed by the main force over flat farmland to relieve Ladysmith 17 miles away.

,

But Buller was reluctant to do so because he feared losing communications over a 30-mile front stretching from the cavalry on the left to the infantry at the base of Spion Kop on the right. Also, at any moment, mounted Boers could break through the extended Khaki Line and attack them from the rear. So, rather than use his cavalry in a wide turning movement, he decided to shorten the route to Ladysmith by pivoting on Spion Kop.

Before Lt.-Gen. Sir Charles Warren, Buller’s second-in-charge, began the assault on the night of 23rd January, he asked his superior to use the artillery to soften-up the Boer gun positions on Tabanyama Hill, but Buller refused.

Leading the attack on 1,400ft-high Spion Kop in darkness and drizzle was Lt.-Col. Alexander Thorneycroft with 1,700 men, mainly the Royal Lancashire Fusiliers and the Royal Lancaster Regiment, plus his own colonial volunteers of Thorneycroft’s Mounted Infantry.

Their overall commander, General E.R.P. Woodgate, ordered his men not to talk or show any light during the hazardous climb and, if attacked, they should not open fire but use their bayonets.

As the head of the column neared the crest, a white spaniel came bounding towards them. They knew that if it barked all would be lost, so a soldier grabbed the dog, made a leash out of a rifle’s pull-through cord and a bugle boy took the spaniel to safety at the foot of the mountain.

That lad was certainly lucky, for Spion Kop was soon to become a place not fit for boys, men or even dogs.

About 20 yards from the crest the British were challenged with a guttural shout: “Wie kom daar?” The infantrymen instantly threw themselves down as the hidden Boers opened fire with their Mauser rifles. In the momentary silence the British heard the click of rifle bolts as the enemy reloaded, and in that split second the order “Charge!” was shouted.

With bayonets fixed, the vanguard lurched forward through the misty darkness and 17 surprised Boers of the Vryheid Commando broke cover and retreated, leaving one man fatally bayoneted.

Because of the thick mist it was impossible for the British to use a lantern to signal to headquarters that the mountain had been taken, so they gave three resounding cheers. The cheers were heard by their comrades far below at 4a.m. on 24th January and, almost immediately, the British artillery opened fire on the presumed Boer positions.

On Spion Kop, Royal Engineer sappers tried to dig entrenchments in the rocky, unforgiving ground with picks and shovels, but it was an impossible task. The trenches were so pitifully shallow that they afforded little protection, and when dawn broke at 4-40 a.m. the Royal Lancasters and South Lancashires were ensconced as best they could on the left (west) flank, with Thorneycroft’s Mounted Infantry in the middle and the Lancashire Fusiliers on the right (east) flank.

Three hours later, when the sun rolled up the curtain of mist, the British were astonished to find that they had not won the entire mountain but merely had a precarious foothold on the edge of a small plateau 900 yards by 500 yards. They also realised that their trenches should have been dug about 400 yards further forward to where the ridge dropped sharply downwards to 2,000 concealed Boers.

The struggle for possession of Spion Kop began when men of the Carolina Commando on Aloe Knoll sprang at the Lancashire Fusiliers less than 200 yards away and actually wrested rifles from them before they recovered from their surprise.

Only 800 yards to the north was Conical Hill, to the north-west was Green Hill, and to the east were the Twin Peaks, all occupied by Boer artillery about to unleash 10-shells-a-minute on the enemy.

General Louis Botha, who commanded the Spion Kop defenders from his headquarters behind Green Hill two miles away, was informed by the Vryheid burghers that the Khakis had taken the Kop. Botha told them: “Well, we must take it back.”

He ordered the long-range “Long Toms” firing shrapnel shells, Krupp howitzers, Creusots and heavy Maxim pom-pom guns into action, and they plastered the massed ranks of invaders from three sides as the commandos re-grouped and climbed back up the mountain.

Rocks on the three Boer-held sides of the plateau shielded them as they crept to within 50 yards of the exposed British and let rip with their German-made Mausers.

The Lancastrians on the right flank were felled by a cyclone of bullets coming at them from Aloe Knoll or they were blown to pieces by shells fired from the three nearby hills until the slaughter was awful to see. In contrast to the accuracy of the Boer artillerymen, the British heavy guns firing from the south were responsible for the deaths of some of their own men.

Gen. Woodgate moved encouragingly among his men with consummate bravery but there was nothing he could do to stem the dreadful butchery. Seventy Lancastrians were felled with bullets to the head and soon after 8-30 a.m. Woodgate was mortally wounded by a shell splinter above the right eye and carried off by volunteer Indian stretcher-bearers.

His second and third in command were then shot dead, leaving Colonel Malby Crofton, CO of the Royal Lancasters, in command. Crofton, who was not a favourite of Gen. Buller’s, found a signaller amid the chaos and told him to send this message to HQ: “Reinforce at once or all is lost. General dead.”

From his HQ on Mount Alice four miles away, Buller watched through his telescope as the barrel-chested, 6ft. 2in. Lt.-Col. Thorneycroft led spirited bayonet charges and sent withering volleys downhill at the advancing commandos.

The confusion of battle was exacerbated by the disruption in the British chain of command. Troops on the peak did not know who their commanding officer was until Buller, after receiving Col. Crofton’s signal, notified Thorneycroft by messenger that he had been promoted to Brigadier-General and was now in charge.

Buller’s order ignored Crofton and other officers who outranked Thorneycroft, and these misunderstandings were never resolved.

The ebb-and-flow of hand-to-hand fighting continued for hours under the blazing sun with neither side in complete control, until eventually the long-distance enfilading rifle fire from both flanks and the Boer shelling decimated the British.

Bodies in the shallow trenches lay three deep, many of them without heads or limbs.

T

At 1 p.m., bereft of their officers and with no water or food, about 200 shell-shocked Lancashire Fusiliers dropped their rifles and waved a white flag. But a Boer officer who came forward to accept their surrender was confronted by a red-faced Thorneycroft who bellowed: “Take your men back to Hell, sir! I am in command and I allow no surrender!”

The ubiquitous Thorneycroft was too late to stop 150 Fusiliers from being captured, but they retaliated soon afterwards by driving the Boers back over the crest-line in a headlong bayonet charge. Apart from this incident, the British never wavered – and neither did the Boers.

It was Thorneycroft who, though bearing a charmed life during 12 hours in the thick of battle, took the decision to retire after calling his surviving officers together late in the afternoon to discuss the futility of continuing the struggle next day.

Churchill went back up the mountain well after dark with a message from Gen. Warren promising reinforcements in the morning, but it had no impact on the physically and emotionally exhausted Thorneycroft.

“The retirement is already in process,” he told Churchill. ”It’s better to get six battalions safely off the hill tonight than a bloody mop-up in the morning.”

Botha spent the night re-organising his commandos and persuading them to re-occupy the mountain, and at dawn two Boer scouts were seen on Spion Kop waving their hats and rifles. Their presence was proof that, almost unbelievably, defeat had turned to victory for the Boers.

Botha rode up later and was so appalled by the ghastly scene that he sent the British a flag of truce and invited them to bury their dead and gather the wounded. The Boers did likewise so, instead of continuing the futile battle, January 25th passed in eerie silence as doctors and Indian stretcher-bearers, among them young lawyer M.K. Gandhi, went about their melancholy task.

Thorneycroft was afterwards held to have greatly erred in retiring against orders from the position he had so nobly held by the sacrifices of his troops. Only his personal bravery in action and his prevention of a fatal surrender mitigated a military crime. His superiors could also not lay the entire blame on him as they had left him for hours without any definite orders or contact. Thorneycroft served with distinction until the end of the Anglo-Boer War and was later made a Companion of the Bath.

British losses on Spion Kop included 322 killed or died of wounds, 563 wounded and 300 taken prisoner, while the Boers counted 95 killed and 140 wounded.

In a bizarre incident on 25th January as the victors were collecting Lee-Enfield rifles from British bodies, one Boer failed to notice that a Lancashire Fusilier’s finger had been stiffened by rigor mortis and was still hooked around the trigger of his elevated rifle. When the Boer gave it a tug, it fired a bullet into his chest, killing him instantly. It is the only known incident of a dead Englishman killing a Boer.

In 1906 a new brick-and-cinder terrace was built at Anfield, the Liverpool football ground, and named The Kop in memory of those who died in the battle. In 1994 the terrace was converted into an all-seat grandstand but retained its historic name.

Even 120 years after the event, the Battle of Spion Kop is burned into the memories of Lancastrians, and battlefield pilgrims from Lancashire still honour the dead by placing Liverpool Football Club insignia on the graves of unknown soldiers who were buried where they fell in 1900.

FOOTNOTE: After a siege lasting 118 days. Gen. Buller’s forces eventually succeeded in breaking through to relieve Ladysmith on 24th February 1900.

English-born Richard Rhys Jones is a veteran South African journalist specialising in history and battlefields. He was the night editor of South Africa’s oldest daily newspaper “The Natal Witness” before going into tourism development and destination marketing. His novel “Make the Angels Weep – South Africa 1958” covers life during the apartheid years and the first stirrings of black resistance. It is available as an e-book on Amazon Kindle.

Published: January 23, 2022.