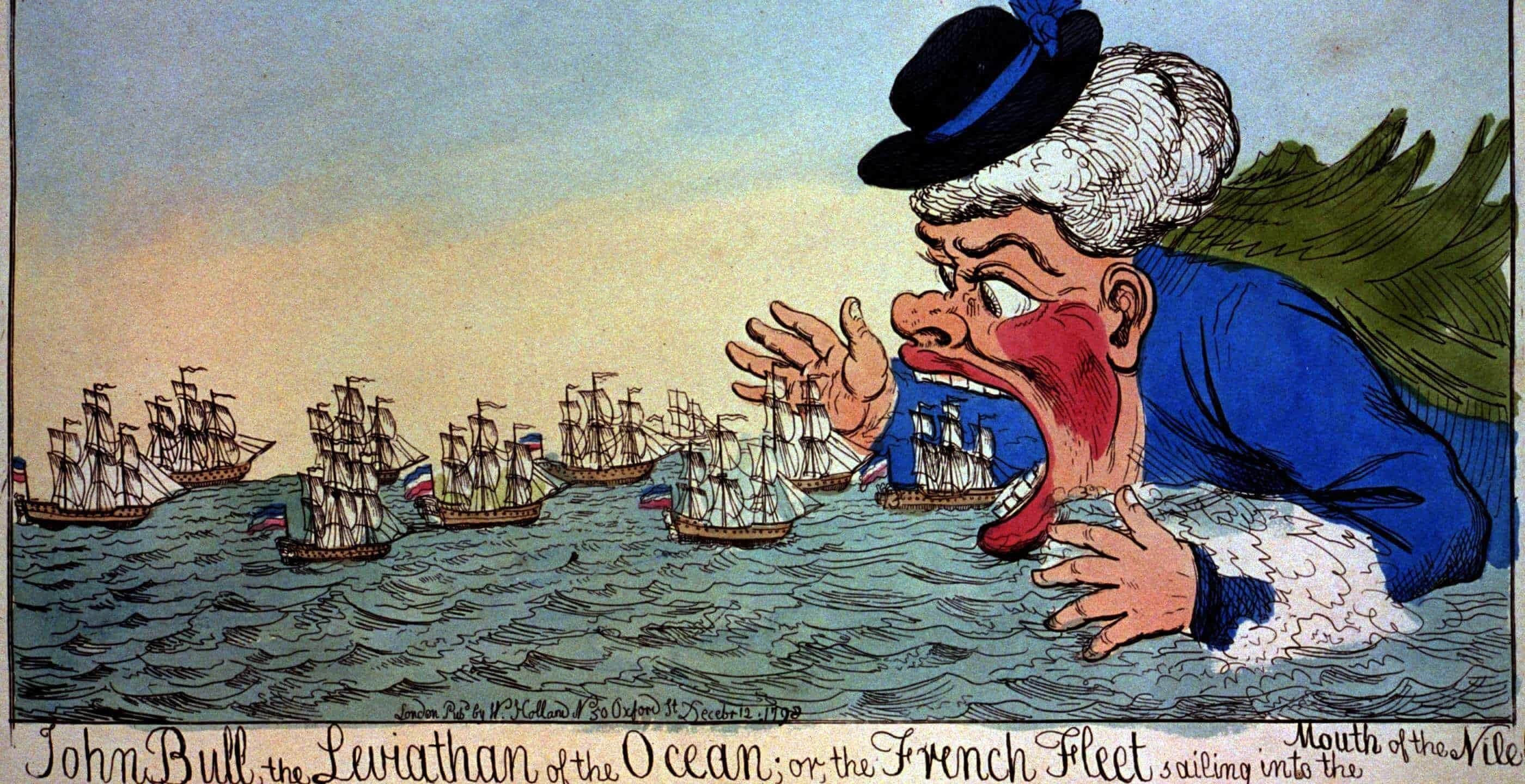

On 1st August 1798 at Aboukir Bay near Alexandria, Egypt, the Battle of the Nile began. The conflict was an important tactical naval encounter fought between the British Royal Navy and the Navy of the French Republic. For two days the battle raged, with Napoleon Bonaparte seeking a strategic gain from Egypt; however this was not to be. Under the command of Sir Horatio Nelson the British fleet sailed to victory and blasted the ambitions of Napoleon out of the water. Nelson, although wounded in battle, would return home victorious, remembered as a hero in Britain’s battle to win control of the seas.

The Battle of the Nile was a significant chapter in a much larger conflict known as the French Revolutionary Wars. In 1792 war had broken out between the French Republic and several other European powers, instigated by the bloody and shocking events of the French Revolution. Whilst the European allies were keen to assert their strength over France and restore the monarchy, by 1797 they were still to achieve their aims. The second part of the war, known as the War of the Second Coalition began in 1798 when Napoleon Bonaparte decided to invade Egypt and hamper Britain’s expanding territories.

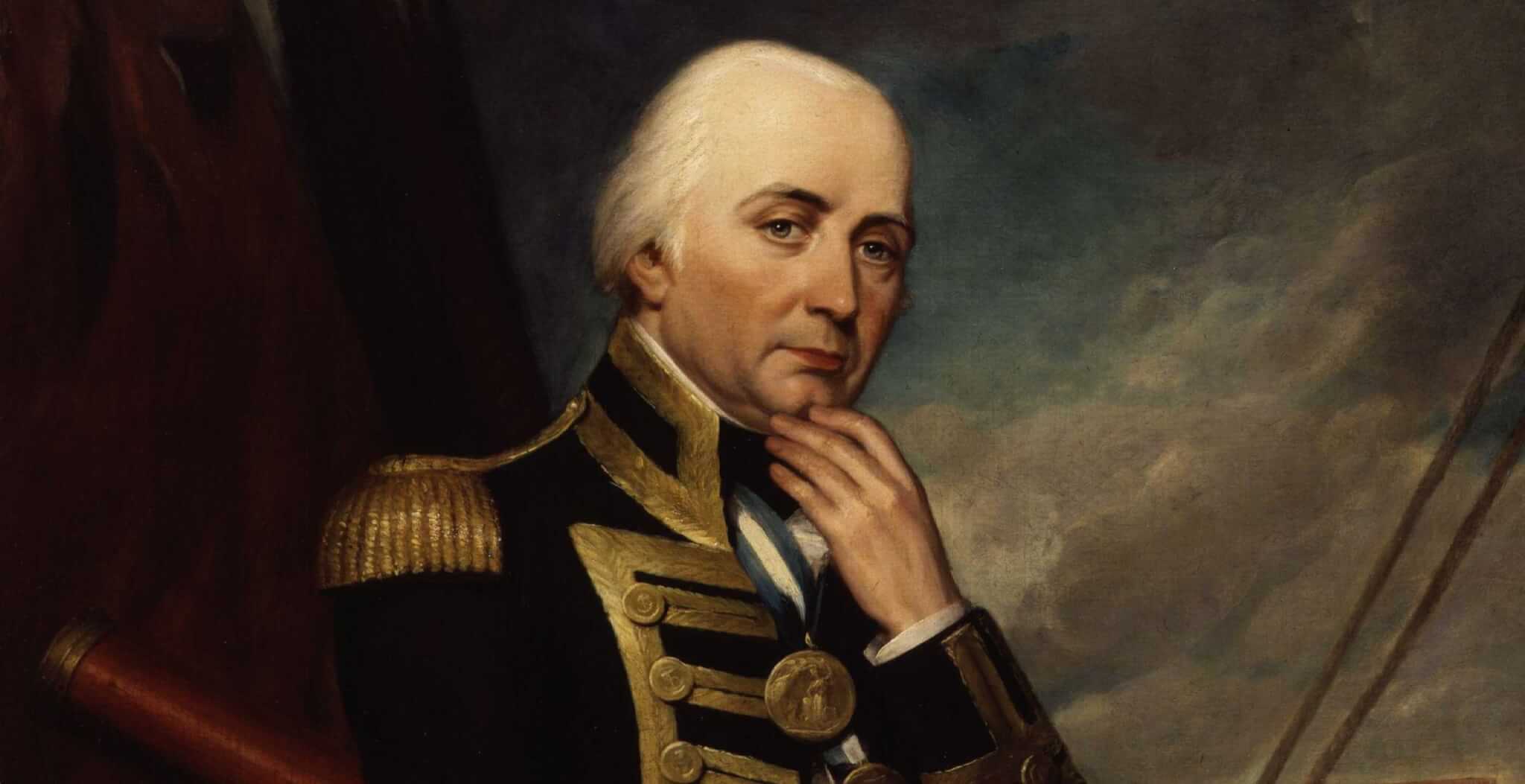

As the French put their plans into action in the summer of 1798, the British government led by William Pitt became aware that the French were preparing for an attack in the Mediterranean. Although the British were unsure as to the exact target, the government gave instructions to John Jervis, the Commander in Chief of the British fleet, to dispatch ships under the command of Nelson to monitor the French naval movements from Toulon. The orders from the British government were clear: discover the purpose of the French manoeuvre and then destroy it.

In May 1798, Nelson sailed from Gibraltar in his flagship HMS Vanguard, with a small squadron with one sole mission in mind, to discover the target of Napoleon’s fleet and army. Unfortunately for the British, this task was hindered by a powerful storm which struck the squadron, destroyed the Vanguard and forced the fleet to disperse, with the frigates returning to Gibraltar. This proved strategically advantageous for Napoleon, who unexpectedly set sail from Toulon and headed south east. This left the British on the back foot, scrambling to adjust to the situation.

Whilst being refitted at the Sicilian port of St Pietro, Nelson and his crew received some much needed reinforcements from Lord St Vincent, bringing the fleet to a total of seventy four gunships. Meanwhile, the French were still steaming ahead in the Mediterranean and had managed to seize control of Malta. This strategic gain caused further panic for the British, with an ever increasing urgency for information as to the intended target of Napoleon’s fleet. Fortunately, on 28th July 1798 a certain Captain Troubridge acquired information that the French had sailed east, causing Nelson and his men to focus their attentions on the Egyptian coastline, reaching Alexandria on the 1st August.

Meanwhile, under the command of Vice-Admiral François-Paul Brueys d’Aigalliers, the French fleet anchored at Aboukir Bay, bolstered by their victories and confident in their defensive position, as the shoals at Aboukir gave protection when forming a battle line.

The fleet was arranged with the flagship L’Orient in the centre carrying 120 guns. Unfortunately for Brueys and his men, they had made a massive error in their arrangement, leaving enough room between the lead ship Guerrier and the shoals, enabling the British ships to slip between the shoals. Furthermore, the French fleet were only prepared on one side, with the port side guns closed and the decks not cleared, leaving them extremely vulnerable. To compound these issues further, the French were suffering from fatigue and exhaustion from poor supplies, forcing the fleet to send out foraging parties which resulted in a large proportion of sailors being away from the ships at any one time. The stage was set with the French worryingly unprepared.

Meanwhile, by the afternoon Nelson and his fleet had discovered Brueys’s position and at six o’clock in the evening the British ships entered the bay with Nelson giving orders for an immediate attack. Whilst the French officers observed the approach, Brueys had refused to move, believing that Nelson was unlikely to attack so late in the day. This would prove to be a massive miscalculation by the French. As the British ships advanced they split into two divisions, one cutting across and passing between the anchored French ships and the shoreline, whilst the other took on the French from the seaward side.

Nelson and his men executed their plans with military precision, advancing silently, holding their fire until they were alongside the French fleet. The British immediately took advantage of the large gap between the Guerrier and the shoals, with HMS Goliath opening fire from the port side with five more ships as back-up. Meanwhile, the remaining British ships attacked the starboard side, catching them in the crossfire. Three hours later and the British had made gains with five French ships, but the centre of the fleet still remained well defended.

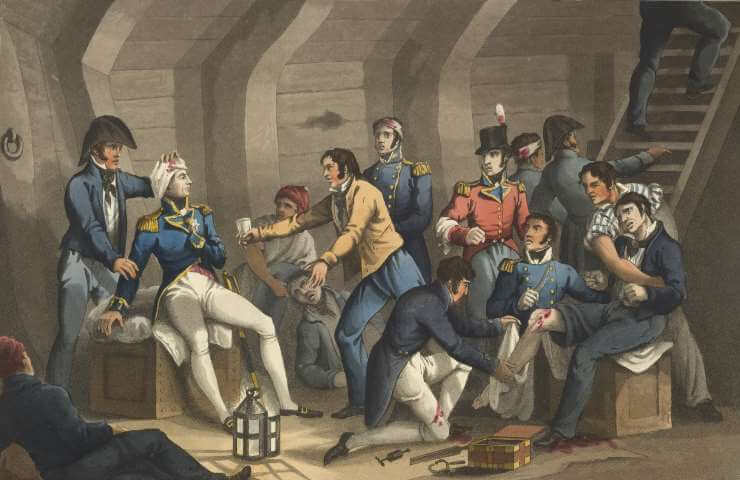

By this time, darkness had fallen and the British ships were forced to use white lamps to distinguish themselves from the enemy. Under Captain Darby, the Bellerophon was almost completely wrecked by L’Orient, but this did not deter the battle from raging on. At around nine o’clock Brueys’ flagship L’Orient caught fire, with Brueys onboard and severely wounded. The ship now came under fire from Alexander, Swiftsure and Leander launching a swift and deadly assault from which L’Orient was unable to recover. At ten o’clock the ship exploded, largely due to paint and turpentine which had been stored on the ship for repainting catching fire.

Nelson meanwhile, emerged onto Vanguard’s decks after recovering from a blow to the head from falling shrapnel. Luckily, with the help of a surgeon he had been able to resume command and witness Britain’s victory unfolding.

The fighting continued into the night, with just two French ships of the line and two of their frigates able to avoid destruction by the British. The casualties were high, with the British suffering close to one thousand wounded or killed. The French death toll was five times that number, with over 3,000 men captured or wounded.

The British victory helped to cement Britain’s dominant position for the rest of the war. Napoleon’s army were left strategically weak and cut off. Napoleon would subsequently return to Europe, but not with the glory and admiration he had hoped for. Conversely, an injured Nelson was greeted with a hero’s welcome.

The Battle of the Nile proved decisive and significant in the changing fortunes of these respective nations. Britain’s prominence on the world stage was well and truly established. For Nelson, this was just the beginning.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 1st August 2018.