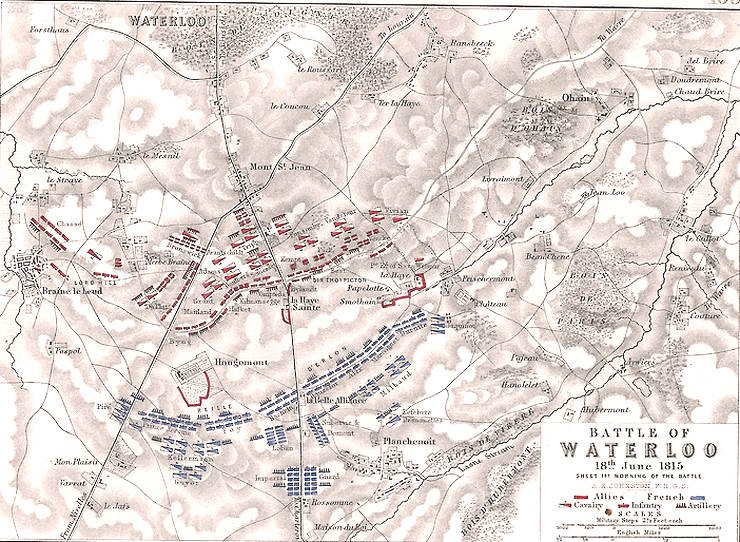

On 18th June 1815, in what was arguably one of the most significant and memorable battles of its era, the Battle of Waterloo brought an end to Napoleon’s power-hungry ambitions for Europe, severing his attempts at domination and concluding a long and arduous war between France and its counterpart powers in Europe.

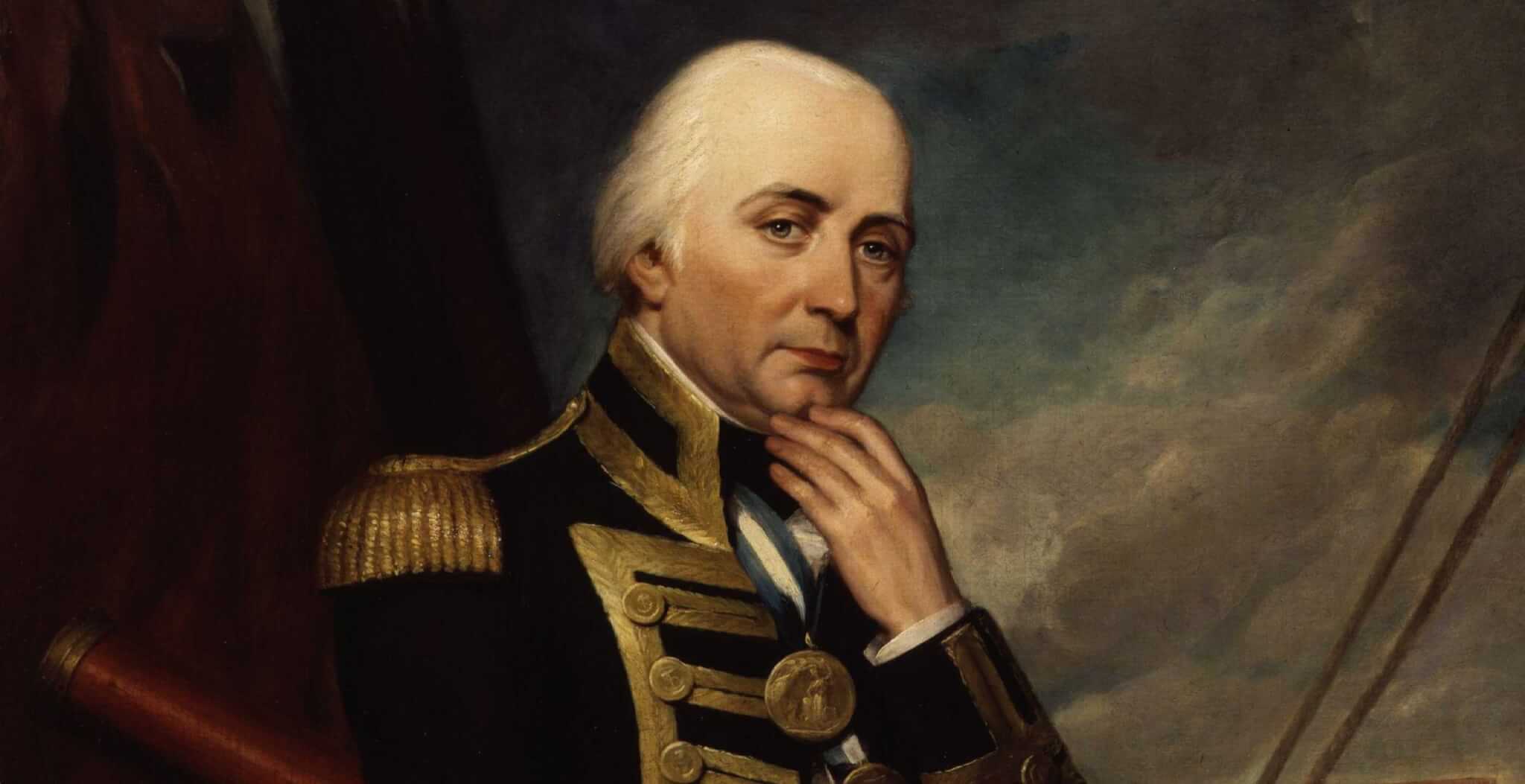

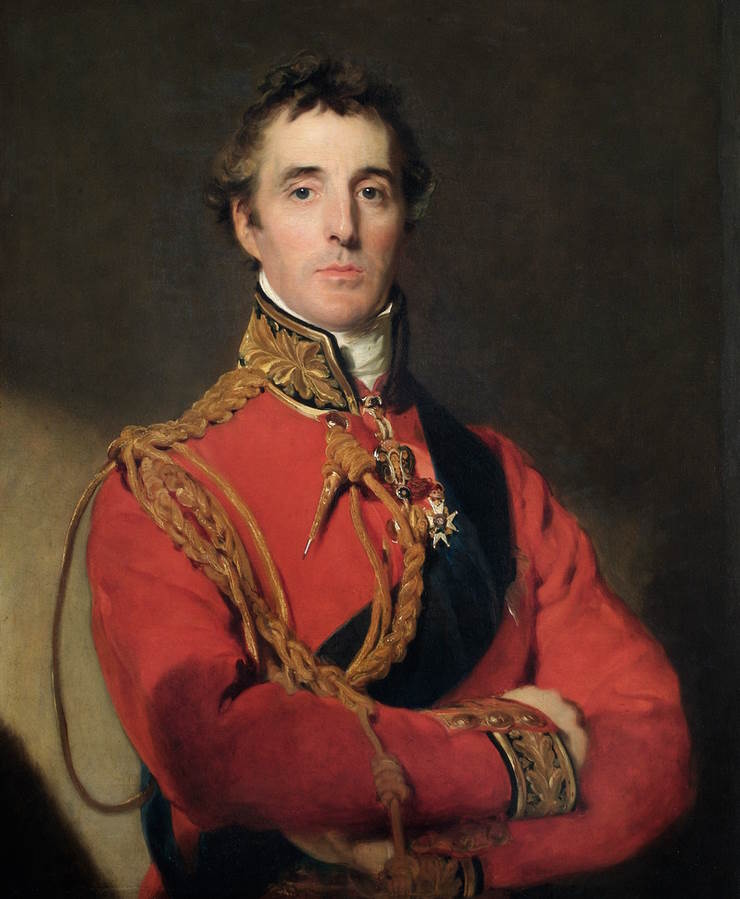

Leading the charge against him was a coalition of European powers, comprising British, German, Prussian, Dutch and Belgian troops headed by the Duke of Wellington and Marshal Blücher.

The battle itself took place just a few kilometres south of the village of Waterloo in Belgium, a modest setting which was about to decide the fate of thousands of Europeans and end the Napoleonic Wars once and for all.

Only a few months previously, the Congress of Vienna had met to discuss the downfall of Napoleon Bonaparte, declaring him an outlaw and making plans for a new political framework in Europe.

In the meantime, the armies of Britain, Russia, Austria and Prussia began to mobilise as Napoleon had by now reached Paris.

Sensing that the European powers were strategically uniting against him, Napoleon realised he needed to act quickly in order to remain in power.

By June, Napoleon had gathered together an army amounting to around 300,000 men. Those who would participate in the subsequent Battle of Waterloo comprised a far smaller number, however they were some of the most experienced among them.

Napoleon’s plan was to not allow the coalition of forces against him to unite, hoping instead to destroy them before they had a chance to amass a larger allied force. Therefore, on 16th June he and his troops attacked the Prussian army at the Battle of Ligny, forcing a withdrawal of Marshal Blücher’s troops further north.

Despite being forced into retreat, the Prussians did not head eastwards and were in fact pushed back to a parallel position to Wellington’s line and therefore would play an important role in the upcoming battle. Whilst the Battle of Ligny was a French victory, it was in fact destined to be Napoleon’s last, as only two days later at Waterloo his long and ambitious military career was about to meet its demise.

Meanwhile, at the Battle of Quatre Bras, Wellington’s Anglo-allied army fought against the left wing of Bonaparte’s troops who were under the command of Marshal Michel Ney.

Whilst the fighting concluded in a tactical victory for Wellington, his troops were still not able to assist the Prussians fighting at Ligny.

Wellington’s men, after hearing the news about Ligny, retreated north whilst the Prussians retreated in the direction of Wavre. Despite this, Wellington’s success on the battlefield helped ultimately to slow down the French advance, as Ney could not maintain control of this area. Therefore Wellington took his position on the battleground of Waterloo, a critical strategic step which some argue was essential for the upcoming allied victory.

Two days later, the final fight was about to ensue. On 18th June 1815, the Allied troops had taken up position under the leadership of the Duke of Wellington who was well-known for his military strategy and defensive acumen, positioning his men in a strategically advantageous position along a ridge.

Meanwhile, Napoleon began leading his army of around 72,000 troops (outnumbering Wellington’s men) towards the battlefield.

In one very important first misstep, Napoleon did not give orders to attack until late morning, due to the sodden ground from the previous night’s thunderstorm. This decision allowed Prussian troops time to join up with the allied forces and support them later in the battle.

Meanwhile, Napoleon began his assault with a diversionary tactic, turning his attentions to Hougoumont chateau which soon became an epicentre of the battlefield. As part of this strategy, Napoleon hoped to draw in Wellington’s troops to protect his right flank, however it soon turned into a much longer encounter with an increasing number of French resources being drawn into the fight rather than the other way around.

In one of the most memorable moments of the attack, an axe-wielding Sous-Lieutenant Legros broke through the north gate of the chateau complex, leading to a bloody fight between the invading French and the allied guards. In response, Macdonnell and Corporal James Graham managed to close the gate and trap the invading Frenchmen, including Legros, inside, leading to a hand-to-hand combat fight to the death where all but a young French drummer boy perished in the Napoleon camp.

With most of the fighting was focused on the chateau, Napoleon was about to engage the second part of his strategy to attack the centre of his enemy, however before he could do so, he witnessed the Prussian reinforcements that were about to re-join Wellington’s troops.

In haste he tried to make contact with his French general and Marshal, Emmanuel de Grouchy who had been given the task of pursuing the retreating Prussians from the previous engagement. As such, this tied up Grouchy at the Battle of Wavre, with the Prussian rear-guard under General Johann von Thielmann in conflict with Marshal Grouchy and around 33,000 of his troops.

Napoleon’s plans were beginning to unravel as his message did not reach him till later that afternoon, at which point Grouchy was embroiled in battle with the Prussians at the Battle of Wavre, dealing a major blow to Napoleon.

Still undeterred, Napoleon attacked Wellington’s troops and opened fire with almost 20,000 infantry under Ney advancing on the allied troops. Such an attack was met with equal firepower by the British infantry who met the French troops and fought back with great effect as the French infantry’s unusual formation hindered their response times.

Sensing this vulnerability, Henry Paget, Earl of Uxbridge and Wellington’s cavalry commander, chose to launch his cavalry against this French infantry column which was now in disarray and pushed them back.

Meanwhile, Lord Edward Somerset and Sir William Ponsonby’s cavalry made a critical error in failing to adhere to Uxbridge’s call to return, which led to a large and needless loss of life by Wellington’s men.

By mid-afternoon some of the most intense fighting had calmed down except for at Hougoumont which was still being held by allied troops despite the increasing number of French soldiers being drawn into battle.

It was soon after that Napoleon gave orders to seize La Hay Sainte. The action, commanded by Ney and two divisions of cavalry, was seen off by the British tactic of infantry square formations which proved highly effective at breaking cavalry charges.

Without infantry to support the charge, after their initial attack failed Ney’s cavalry regrouped, however their second attempt was driven off by Uxbridge’s cavalry.

Napoleon was still supportive of this manoeuvre however, and by late afternoon around 9000 cavalry men were committed to the attack.

In the meantime, Napoleon’s right flank became suddenly exposed to enemy fire from the Prussians who had managed to re-join their allies just in time after half a day’s marching through the countryside.

By 6 o’clock in the afternoon Ney had finally captured La Haye Sainte after a prolonged cavalry attack. In the coming hour, the decisive action was about to take place; knowing that time was of the essence, the French troops had to overwhelm Wellington’s men before more Prussians arrived.

The allied forces were exhausted and depleted, leaving their centre vulnerable to attack. Ney noticed this and asked for reinforcements, however Napoleon refused as he was preoccupied with defending his right flank. This would prove to be a critical mistake.

By late afternoon, Napoleon had secured his right flank and now turned his attention to the front, however Wellington in this time had also been able to regroup and organise his men.

Napoleon gave the order to six battalions of the Guard to join Ney with all of these battalions taking part in the assault on exposed and unprotected slopes, ripe for attack from the enemy.

Wellington’s men and guns were directly in their path and despite the great skill and bravery of French troops, nothing could be done in such a position. As the first who came under attack began to flee, so too did the rear troops, beginning a chaotic large-scale withdrawal.

Only a quarter of an hour after seeing this retreat by the French Guard, Wellington ordered an advance, forcing the French army into a trap where Prussian and British troops began to converge from different directions.

Later that evening, Blücher and Wellington met each other once more and a final order was given for the Prussians to continue their pursuit, forcing the French retreat further and further back.

Victory for the allied forces was thus confirmed and Wellington’s men had secured victory against the enormity of Napoleon’s troops, ending years of conflict and strife.

Such success was not without its setbacks as casualties remained high on both sides. With thousands of Wellington’s troops dead, he was said to have reflected on this loss:

“Believe me, nothing except a battle lost can be half so melancholy as a battle won.”

Whilst the reality of victory for Wellington and his men set in, Napoleon fled to Paris and on 22nd June abdicated. A month later, after attempting to escape the hands of his enemy, Napoleon eventually surrendered on 15th July and spent the rest of his life on the island of St Helena.

Wellington went on to serve as British Prime Minister whilst Napoleon languished in exile, forced to reflect on his errors and tactical failures.

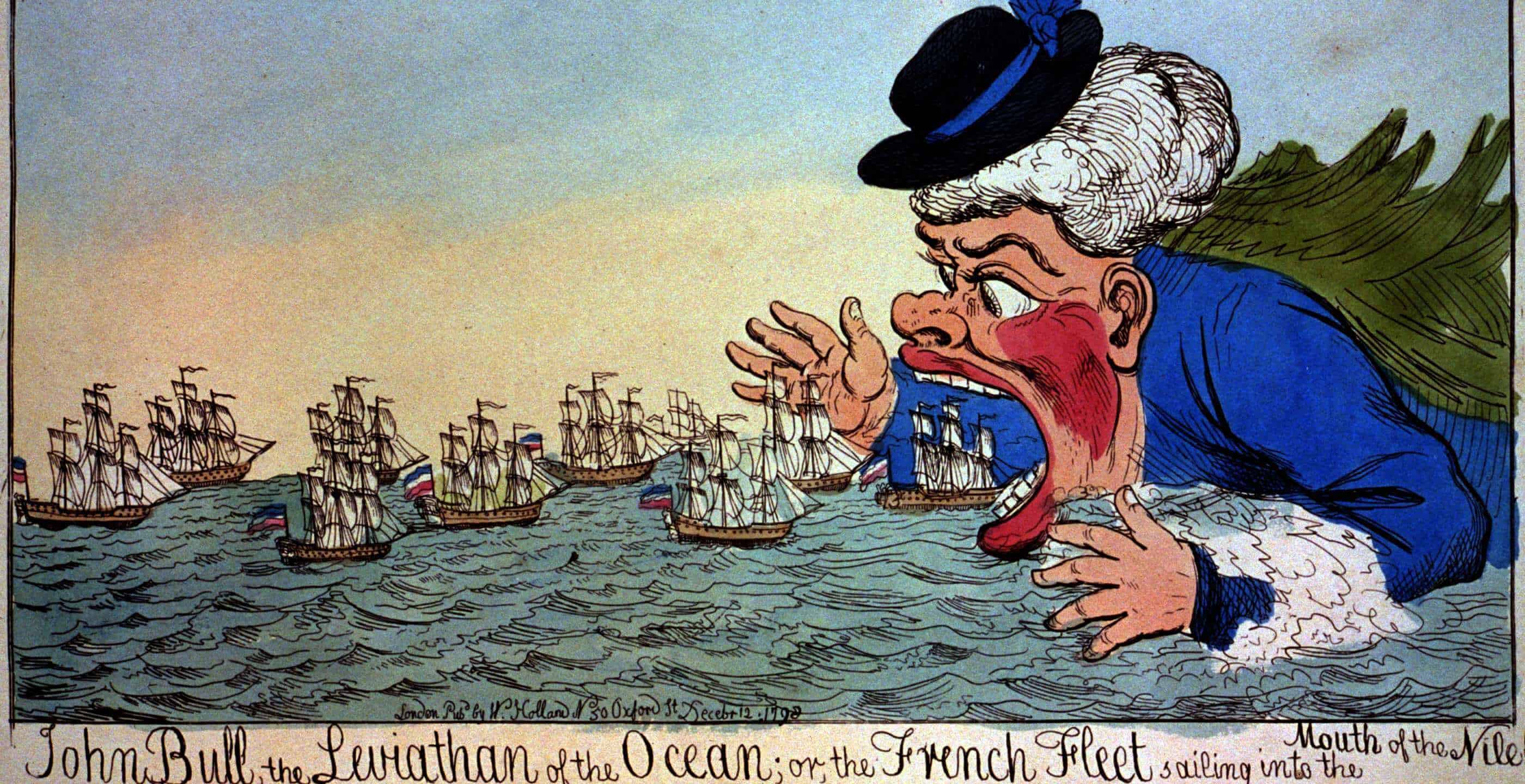

The Battle of Waterloo reached its conclusion and with it was not only secured a French defeat but the end of Napoleon’s military and public career. The First French Empire had met its demise and with it brought an end to years of conflict in Europe. The period known as Pax Britannica had been reached.

After years of constant fighting in Europe, war was over. The ordinary man and woman could breathe a sigh of relief. As a kind of catharsis set in, only time would tell when such hostilities would emerge again….

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 25th July 2023.