Not a drum was heard, not a funeral note,

As his corse to the rampart we hurried;

Not a soldier discharged his farewell shot

O’er the grave where our hero we buried.

These words are taken from the poem, “The Burial of Sir John Moore after Corunna”, written in 1816 by the Irish poet Charles Wolfe. It soon grew in popularity and proved to be a pervasive influence featuring in anthologies throughout the nineteenth century, a literary tribute honouring the fallen Sir John Moore who met his grisly fate at the Battle of Corunna.

On the 16th January 1809 the conflict played out, fought between the French and British forces on the north-west coast of Spain in Galicia. Corunna was to be the setting for one of the most notorious and harrowing incidents in British military history.

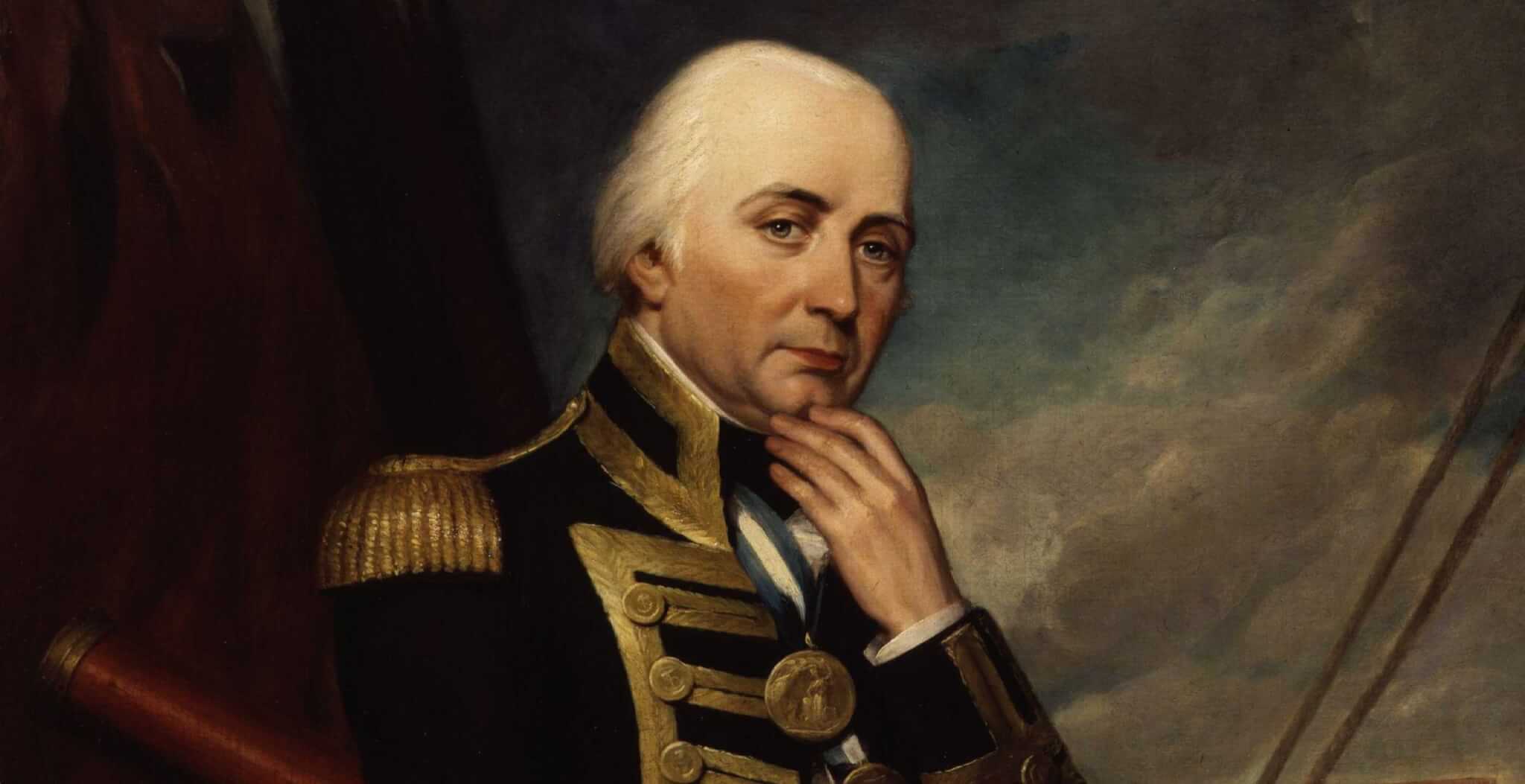

A rear guard action for the retreating British army, led by Sir John Moore would allow the soldiers to escape, evoking similar images to that of Dunkirk. Unfortunately, this action was only completed at the expense of their own leader, Moore, who did not survive the evacuation, a man not to be forgotten; he has since been commemorated in statues in Spain and Glasgow.

The battle itself was part of a much wider conflict known as the Peninsular War which was fought between Napoleon’s forces and Bourbon Spanish soldiers in a bid to control the Iberian Peninsula during the Napoleonic Wars. This proved to be a time of great upheaval in Europe and Britain soon found itself involved.

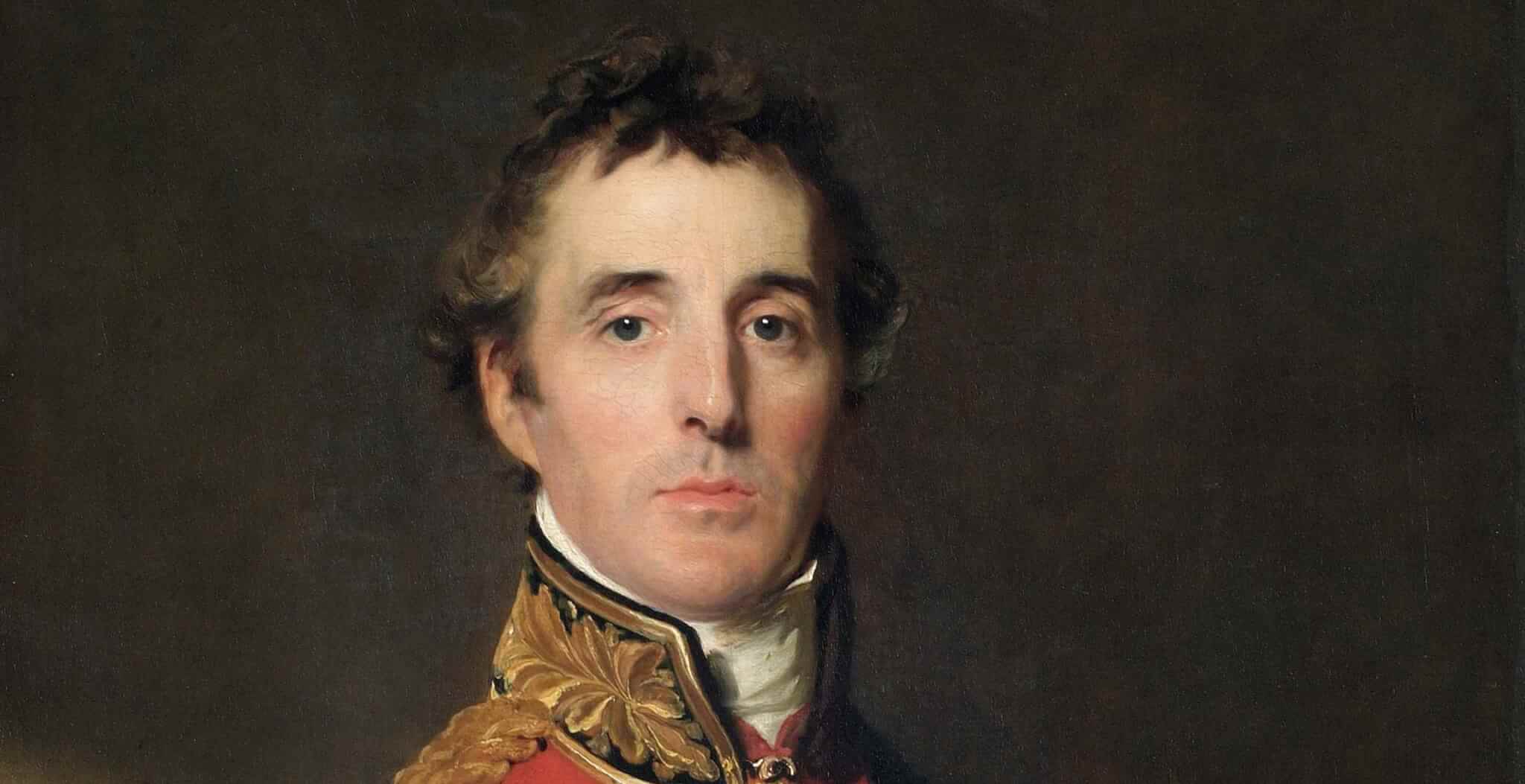

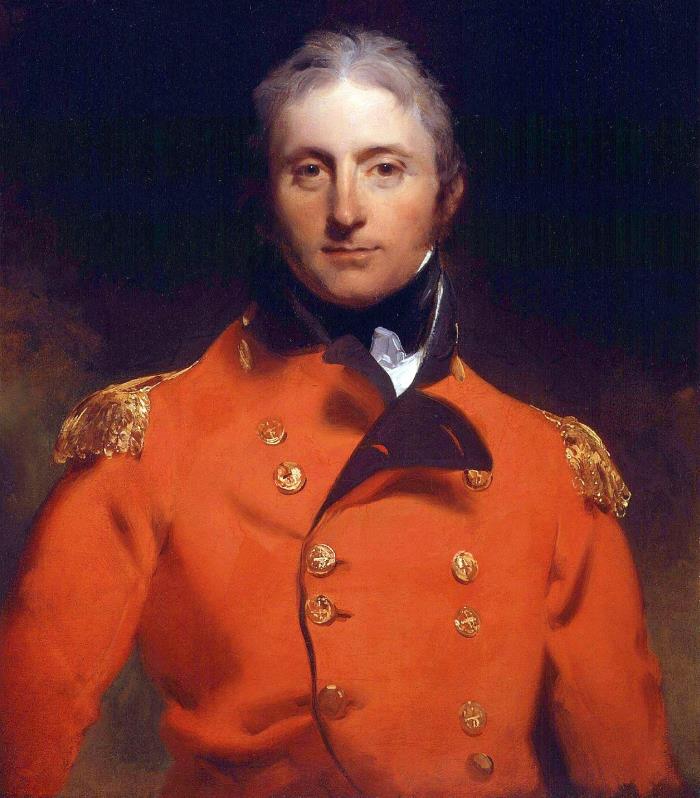

In September 1808 an agreement was signed known as the Convention of Cintra in order to settle the arrangements for French troops to withdraw from Portugal. This was based on the defeat suffered by the French led by Jean-Andoche Junot who failed to beat the Anglo-Portuguese soldiers fighting under Sir Wellesley’s command. Unfortunately, whilst instigating a French retreat, Wellesley found himself displaced by two elder army commanders; Sir Harry Burrard and Sir Hew Dalrymple.

Wellesley’s plans to push the French further had been scarpered, and his ambition to take more control of a region known as Torres Vedras and cut off the French had been rendered null and void by the Cintra Convention. Instead, Dalrymple agreed to conditions which amounted almost to a surrender despite British victory. Furthermore, around 20,000 French soldiers were allowed to leave the area in peace, taking with them “personal property” which in fact was more likely to be stolen Portuguese valuables.

The French returned to Rochefort, arriving in October after a safe passage, treated more as victors than defeated forces. The decision by the British to agree to these conditions was met with condemnation back in the United Kingdom, disbelief that French failure was turned into a peaceful French retreat facilitated largely by the British.

In this context, a new military leader came onto the scene and in October, Scottish-born General Sir John Moore took command of the British forces in Portugal, amounting to almost 30,000 men. The plan was to march across the border into Spain in order to support the Spanish forces which had been fighting Napoleon. By November, Moore began the march towards Salamanca. The aim was clear; impede French forces and hinder Napoleon’s plans to put his brother Joseph on the Spanish throne.

Napoleon’s ambitious plans were equally impressive, as by this time he had amassed an army of some 300,000 men. Sir John Moore and his army stood no chance in the face of such numbers.

Whilst the French engaged in a pincer movement against Spanish forces, the British soldiers were worryingly fragmented, with Baird leading a contingent in the north, Moore arriving at Salamanca and another force stationed east of Madrid. Moore and his troops were joined by Hope and his men but upon arrival to Salamanca, he was informed that the French were defeating the Spanish and thus found himself in a difficult position.

Whilst still unsure as to whether to retreat to Portugal or not, he received further news that the French corps led by Soult were in a position near the Carrión River that was vulnerable to attack. The British forces strengthened as they met with Baird’s contingent and subsequently launched an attack at Sahagún with General Paget’s cavalry. Unfortunately, this victory was followed by a miscalculation, failing to launch a surprise offensive against Soult and allowing the French to regroup.

Napoleon decided to seize the opportunity to destroy British troops once and for all and began to gather the majority of his troops to engage with the advancing soldiers. By now, the British troops were well into the Spanish heartland, still following plans to join up with the beleaguered Spanish forces in need of help against the French.

Unfortunately for Moore, as his men were now on Spanish soil it became increasingly obvious that Spanish troops were in disarray. The British troops were struggling in terrible conditions and it became clear that the task at hand was futile. Napoleon had been gathering more and more men in order to outnumber the opposing forces and Madrid was by now already under his control.

The next step was simple; British soldiers led by Moore needed to find a way to escape or risk being totally obliterated by Napoleon. Corunna became the most obvious choice to launch an escape route. This decision would end up being one of the most difficult and perilous retreats in British history.

The weather was hazardous with British soldiers forced to cross over the mountains of Leon and Galicia in harsh and bitter conditions in the middle of winter. As if the circumstances were not bad enough, the French were in quick pursuit led by Soult and the British were forced to move quickly, fearing for their lives as they did.

In the context of increasingly bad weather and with the French hot on their heels, the discipline in the British ranks began to dissolve. With many men perhaps sensing their impending doom, many of them looted Spanish villages along their retreating path and became so drunk they were left behind to face their fate at the hands of the French. By the time Moore and his men had reached Corunna, almost 5000 lives had been lost.

On 11th January 1809, Moore and his men, now with numbers reduced to around 16,000, arrived at their destination of Corunna. The scene that greeted them was an empty harbour as the evacuation transport had not yet arrived, and this only increased the likelihood of annihilation at the hands of the French.

Four long days of waiting and the vessels eventually arrived from Vigo. By this time the French corps led by Soult had begun to approach the port hindering Moore’s evacuation plan. The next course of action taken by Moore was to move his men just south of Corunna, close to the village of Elviña and near to the shoreline.

On the night of the 15th January 1809 events began to play out. The French light infantry amounting to around 500 men were able to drive the British from their hilltop positions, whilst another group pushed the 51st Regiment of Foot back. The British were already fighting a losing battle when on the following day the French leader, Soult, launched his great assault.

The Battle of Corunna (as it became known) took place on 16th January 1809. Moore had made the decision to set up his position at the village of Elviña which was key for the British to maintain their route to the port. It was at this location that the bloodiest and most brutal fighting took place. The 4th Regiment were strategically pivotal as well as the 42nd Highlanders and the 50th Regiment. Initially pushed out of the village, the French were quickly met with a counterattack which totally overwhelmed them and allowed the British to retake possession.

The British position was incredibly fragile and once more the French would instigate a subsequent attack forcing the 50th Regiment to retreat, closely followed by the others. Nevertheless, the valour of British forces was not to be underestimated, as Moore would end up leading his men once again into the epicentre of the fight. The General, backed by two of his regiments, charged back into Elviña engaging in ferocious hand-to-hand combat, a battle which resulted in the British pushing the French out, forcing them back with their bayonets.

A British victory was on the horizon but just as the battle began to swing in favour of Moore and his men, tragedy struck. The leader, the man that had led them across treacherous terrain and maintained a fighting stance to the very end, was hit by a cannon ball in the chest. Moore was tragically wounded and was carried to the rear by the highlanders who had begun to fear the worst.

Meanwhile, the British cavalry were launching their final attack as night fell, beating the French and cementing British victory and a safe evacuation. Moore, who was critically wounded, would live a further few hours, enough time to hear of the British victory before he passed away. The victory was bittersweet; Moore died alongside 900 others who had fought bravely, whilst on the opposing side the French had lost around 2000 men.

The French might have managed to win a hasty British withdrawal from the country but Britain had won a tactical victory at Corunna, a triumph which had the odds stacked against it. The remaining troops were able to evacuate and they soon set sail for England.

Although the Battle of Corunna was a tactical victory, the battle also exposed the failures of British military, and Moore received both admiration and criticism for his handling of events. When Wellesley, better known as the Duke of Wellington, returned to Portugal some months later, he looked to put many of these failures right.

In fact, Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington would go on to achieve victory, fame and fortune was said to have remarked, “You know, Fitzroy, we’d not have won, I think, without him”. Whilst Moore’s defiance against overwhelming numbers of French troops has often been overshadowed in the historical narrative, his strategic victory left a legacy for military leaders following in his footsteps.