TAKE a pompous general who objects to fighting before breakfast, 200 cavalrymen who disappear into thick mist, Irishmen shooting at one another on opposite sides, and British infantrymen shelled by their own artillery – and you have the tragicomic ingredients for the Battle of Talana.

The opening engagement of the Anglo-Boer War on 20 October 1899 turned out to be a humbling experience for the complacent British forces in South Africa.

Fought a couple of miles from Dundee in Northern Natal, it was a result of President Paul Kruger refusing to grant the franchise to Uitlanders in the Transvaal, as demanded by Britain’s Colonial Secretary, Joseph Chamberlain.

Had Kruger agreed to an unconditional franchise to the Uitlanders (most of whom were British) after they had lived in the Transvaal for five years, Chamberlain would have been satisfied. If Kruger had accepted these terms, a settlement would have surely followed. Even his Afrikaner allies in the Cape and Orange Free State urged Kruger to make concessions, but he refused. He believed that Chamberlain had set a trap to humiliate the Afrikaners before destroying them. Kruger told his allies: “With God before our eyes we cannot go further without endangering our independence.”

Distrust between the Transvaal and Britain stemmed from the ill-fated Jameson Raid of 1896. The Raid was the real declaration of war in the conflict and, for the next four years until 1899, the defenders prepared for the inevitable and the aggressors consolidated their alliance.

Kruger was determined to invade the British colony of Natal before Britain could send reinforcements by sea. With a numerical advantage of 40 000 Boers against the 15,000 British troops already in South Africa, Kruger aimed to capture Durban before the first troop ships arrived, but on 9 September 1899 the British Cabinet agreed to send 8,000 more troops. President Marthinus Steyn of the Orange Free State was not convinced that war was inevitable until the British marched their troops from Ladysmith to Dundee on 25 September. More British troops arrived by ship in Durban on 9 October and Steyn’s doubts were finally resolved. But his uncertainty cost the Boers a four-week advantage.

Kruger demanded that Britain withdraw her troops on the borders of the Transvaal Republic and send home the reinforcements within two days, otherwise this would be considered a formal declaration of war.

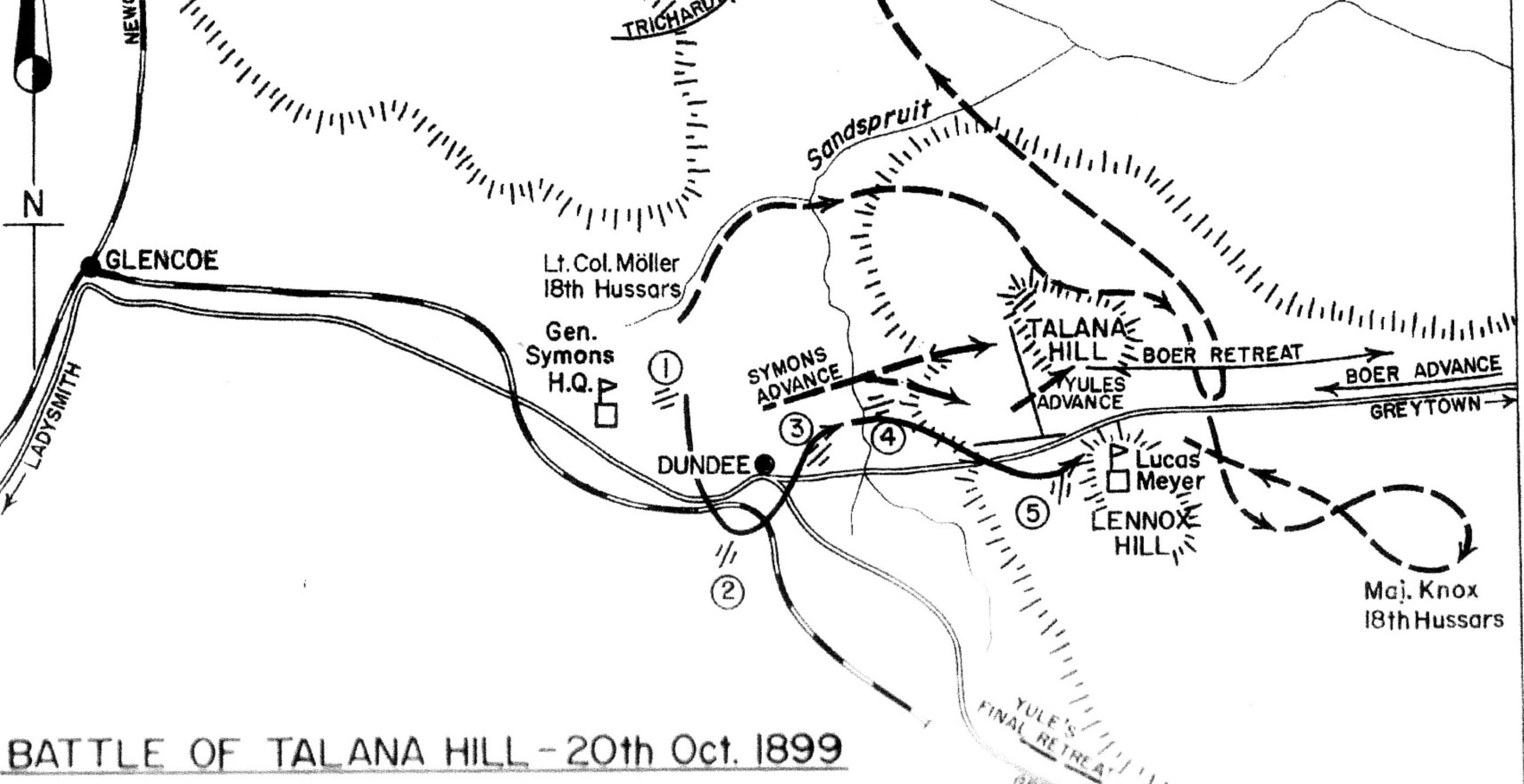

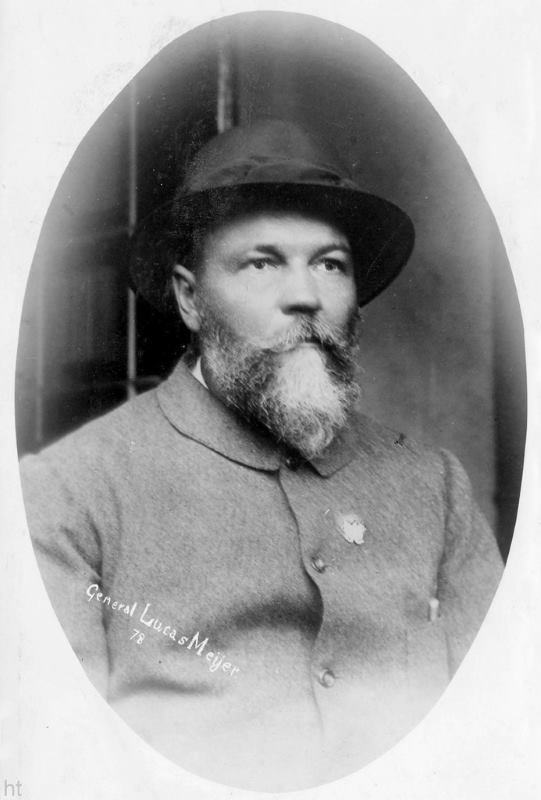

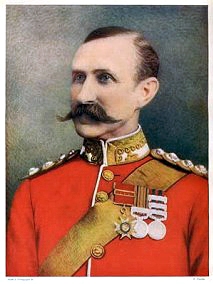

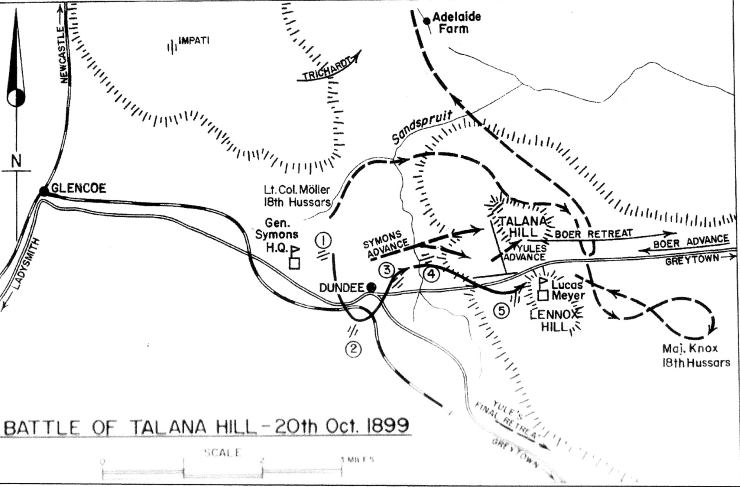

General Lucas Meyer commanded 3,000 men of the Wakkerstroom commando who were deployed near Dundee. There were 10,000 British troops in Natal but Lieutenant-General Sir William Penn Symons, who was in command before Sir George White’s arrival on 7 October, split the force by taking 4,000 men north from Ladysmith to Dundee.

On 11 October the Dundee garrison camping under Impati Hill heard that Kruger’s ultimatum had expired, but for another nine days it remained business as usual in the officers’ mess. Although there was a water shortage, one young officer recorded: “There was no shortage of whisky and soda.” Some officers were accompanied by their wives and talked about celebrating Christmas in Pretoria. But the Boers had other ideas…

Lieutenant-General Sir William Penn Symons, who was mortally wounded at Talana.

Lieutenant-General Sir William Penn Symons, who was mortally wounded at Talana.

Penn Symons, who seemed contemptuous of his Boer adversaries, became aware the enemy was near when his scouts exchanged fire with Meyer’s patrol two miles from Dundee at 3-20 a.m. on Friday 20 October. That was when his force should have taken control of the heights of Talana and Impati. Instead, with a curtain of thick mist hanging over Impati, he was content to await the invaders.

At 5-40 a.m. the unopposed Boers were spotted on Talana Hill with two French Creusot field guns, and almost immediately the first 75 mm shells splashed into the wet earth behind the British camp. Penn Symons was about to eat breakfast when the first shell landed, but failed to explode in the rain-sodden ground.

“Damned impudence of the Boers to start shelling before breakfast!” he spluttered to his aide-de-camp, and ordered the 18 British guns placed in position two miles from the Boers to return the fire.

When the Boer guns stopped firing after an hour there were only two casualties – a bugle boy whose head was taken off by a shell and a horse blown apart by a direct hit.

Penn Symons then ordered the assault on Talana to prevent Meyer from linking up with General Daniel Erasmus and his 2,000 Boers who were already on top of Impati but rendered useless by the thick mist.

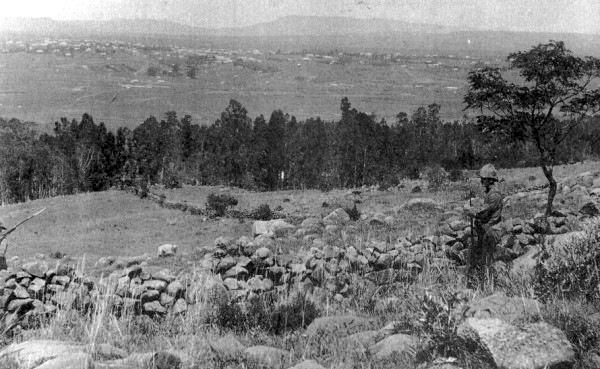

Talana looked featureless but it was terraced by erosion and had a couple of protective farm walls on the lower slopes. Penn Symons decided on conventional tactics – the artillery duel, an infantry attack, and then a cavalry charge to cut off the Boer retreat. The Royal Dublin Fusiliers led the attack, supported by the Kings Royal Rifles (the 60th) and the Royal Irish Fusiliers.

Colonel B. D. Möller’s 300-strong cavalry (the 18th Hussars) rode off prematurely at 7 a.m. with orders to await the Boer retreat behind Talana. Möller and 200 riders disappeared into the swirling mist and Major Knox led the remaining 100 Hussars towards Lennox Hill in a pincer movement.

Gen. Penn Symons, always conspicuous because of the red pennant carried by the ADC at his side, then ordered the infantry to attack Talana Hill in close order. They were immediately repulsed, the leading closely-packed soldiers being cut down by Boer marksmen hidden on the misty hilltop. The wounded were scooped up by Indian stretcher-bearers and taken to a field hospital. The rest reached the cover of the eucalyptus trees where a graveyard now stands.

It was difficult for the British to advance under the deafening tempest of Mauser fire from above. Bullets ricocheted off rocks and splashed into the ground like a rainstorm on a lake. Above their heads shrapnel burst in balloons of white smoke and red dust, and the shredded leaves fell in swathes. The air was filled with the pungent smell of eucalyptus and the sharp odour of cordite.

Concerned about the slow advance, Gen. Penn Symons rode up just after 9 a.m. to find out why the infantry had made little progress. He was informed about the deadly Boer rifle fire and it was suggested that the artillery should try some more softening-up, but Penn Symons refused because he was intent on routing Meyer’s commandos before Erasmus’ force arrived.

The impatient General rode through the woods, dismounted, and strode through a gap in a stone wall to urge his men forward, but he was shot in the stomach. He struggled back to his horse and Indian stretcher-bearers took him to the field hospital, where it was discovered that he had a mortal stomach wound.

The British inched forward and at 10 a.m. reached a second wall on the hillside. A Captain Nugent described how he and a companion, both wounded, managed to reach the crest of Talana, only to be shelled by their own artillery. Fortunately, the Boers did not attempt to exploit the artillery’s error, but crept away down the reverse side of Talana Hill where their horses were tethered and rode off.

By midday the hill had been won by the British, but at great cost. Fifty-one had been killed and 203 wounded, some by their own artillery. Colonel Robert Gunning of the 60th Regiment had been shot through the heart as he stood up near the crest to shout at his own artillerymen to stop firing. Captain Connor of the Fusiliers was mortally wounded in the stomach and Lt. Hambro lost both his legs, smashed by British shrapnel.

The official dispatch made no mention of the shambles but it seems likely that the confusion was caused by Penn Symons being wounded and the issue of imprecise orders to the gunners.

Col. Möller’s Hussars became totally lost in the thick mist and ended up at Adelaide Farm near Impati, and when the mist cleared they were quickly surrounded and made prisoners by the Irish-American volunteers of Erasmus’ force.

Major Knox and his 100 cavalrymen on the right flank were attacked near Lennox Hill by Boers who had crept within 300 yards of the British. When two of his men and three horses were hit, Knox withdrew his two squadrons and galloped back to camp, enabling General Meyer and his 3,000 men to escape unchallenged. When the thick mist lifted on Saturday 21 October, General Erasmus’ gunners on the heights of Impati began shelling Dundee with the Krupp 40-pounder (the Long Tom), which outranged the British 15-pounders. The first 5 in. shell killed a young British officer and then shells crashed into the field hospital – despite the Red Cross flag fluttering above the tent.

Major-General James Yule, who had taken over command from the wounded Gen. Penn Symons, received orders from Sir George White to fall back to Ladysmith, because White could not reinforce Dundee without sacrificing Ladysmith.

The Dundee defenders were almost surrounded by 10,000 Boers and the request to retreat was nevertheless humiliating for Yule and his garrison. White was forcing Yule to leave Dundee to the enemy, plus the garrison’s two months supply of food and stores (valued at £350,000) and their own wounded, including the dying Gen. Penn Symons.

At about 10 p.m. the troops moved out in pouring rain and darkness on a three-day march to Ladysmith. Not realising the British had left, Boer shells from Impati smashed into the field hospital tents at 10-30 a.m. the next day, so a Medical Corps captain volunteered to ride up the rocky track to the Boer position carrying a white flag. Two hours later, a couple of Boers in civilian clothes rode into Dundee and formally accepted the British surrender, to be followed by hundreds of Boers who galloped in and looted the camp.

Penn Symons died during the afternoon, but not before he told the medical staff that he regarded Yule’s retreat as a betrayal. The Boers sewed his body into a Union Jack and took it in procession to St. James’ Church cemetery. As the cortege passed, the Boers doffed their hats and many attended the funeral service.

After the surrender, 38 wounded Britons were sent to captivity in Pretoria and the more seriously wounded were handed over to their comrades in Ladysmith. The Boers had been driven from Talana’s crest with the loss of 150 killed but the British suffered 500 fatalities.

Gen. Yule’s retreat left Dundee, Glencoe and the Natal coalfields in Boer hands and caused Ladysmith to be besieged for six months before the tide of the war eventually turned in favour of the British.

English-born Richard Rhys Jones is a veteran South African journalist specialising in history and battlefields. He was Night Editor of South Africa’s oldest daily newspaper “The Natal Witness” before going into tourism development and destination marketing. His historic novel “Make the Angels Weep” covers life during the apartheid years and the first stirrings of black resistance. Published in 2017, it is available as an e-book from Amazon Kindle.

Publish date: 17th October 2022.