THE Royal Navy’s “Grand Old Lady,” the famous battleship HMS Warspite, was driven by a storm onto Cornwall’s rocks on 12th April 1947 while being towed to a ship-breakers’ yard on the River Clyde.

Although greatly saddened to learn about his former ship’s ignoble fate after it had survived two world wars, my late father, Lt. Fred Jones, who was a proud member of her crew for more than four years, commented: “She was eventually broken up where she lay by British workmen doing what the enemy failed to do.”

Commissioned in 1915, the 32 000-ton Warspite was the seventh ship to bear the name, which dates from the reign of Queen Elizabeth I and England’s wars with Spain. The motto on the ship’s crest “Belli dura despicio” means “I despise the hardships of war.”

Warspite took part in 15 major engagements, from Jutland in World War 1 to 14 actions in World War 2. These included the Atlantic convoys, Narvik, Norway, Calabria, the Mediterranean, the Malta convoys, Matapan, Crete, Sicily, Salerno, the English Channel, Normandy and the Bay of Biscay.

She fired her guns for the last time whilst bombarding German strongholds on Walcheren Island in the Scheldt Estuary in November 1944, earning the most battle honours ever awarded to one warship.

My father Fred Jones joined Warspite in May 1937 after the 24-year-old ship had undergone a full-scale re-fit in Portsmouth dockyard. Her main machinery had been entirely renewed, one of the original two funnels was removed to make way for more anti-aircraft armament, and the eight 15-inch guns were elevated to 30 degrees to increase their range to 32,000 yards (16 miles).

The anti-aircraft defence armament had been boosted to four 4-inch twin mountings, two eight-barrelled 2-pounder pom-poms (nicknamed “Chicago Pianos” by the crew) and twin Oerlikons. A hangar was placed behind the funnel to house two seaplanes that could be catapulted off and hoisted back on board by a crane.

Her crew numbered 1284, including Chief Petty Officer/Gunner’s Mate Fred Jones, who was captain of “B” turret.

Leaving Portsmouth, HMS Warspite sailed for the Mediterranean to become the flagship of Admiral Sir Dudley Pound. She was based in Alexandria which, with war imminent, was to be the fleet’s base.

On 3 September 1939 Admiral Pound received a signal from the Admiralty that read: “Commence hostilities at once with Germany,” and Warspite was sent to escort 30 merchant ships in convoy across the Atlantic from Canada to Britain.

When the armed merchant cruiser Rawalpindi was sunk by the Scharnhorst in the North Sea, Warspite joined a search for the German battle-cruiser, but she slipped away in the foggy Icelandic weather.

Her first major action was the Battle of Narvik, fought on 13 April 1940 to prevent the shipment of iron ore from the Norwegian port to Germany. Warspite and nine destroyers left Scapa Flow and entered Ofot Fiord to attack German ships and shore defences. The Swordfish aircraft was catapulted off, bombed and sank a German submarine at its moorings, and reported the position and strength of the defenders.

Although Warspite was bows-on to the targets and could fire only the four forward guns, nine German destroyers were sunk and the port facilities were badly damaged.

Writing his memoirs after the war, my father described the battles he took part in and explained how the huge 15-inch guns (in turrets “A” and “B” forward and “X” and “Y” aft) were loaded and fired.

Each turret weighed about 700 tons. The guns were 54 feet long and weighed 100 tons. They consisted of a rifled tube over which was shrunk the outer jacket. A gun’s “life” ended after firing 335 rounds and it then had to be re-lined.

A turret’s hydraulic machinery raised the ammunition lying some 50 feet below in the magazine. Each shell weighed almost a ton and a slick crew could load one-shell-a-minute. Normal practice was to fire four-gun salvoes from the right guns of all turrets, followed by a similar salvo from the left guns.

To a stranger, the incessant and overwhelming noise inside the turret as every member of the 70-man crew did his job with split-second precision was equalled only by the unnerving blinding flash and stunning concussion of the firing. But to the men who controlled and worked the great guns it all became second nature.

Fred Jones takes up the story:

“For us, the Battle of Narvik begins with the order “Action stations.” The gun crews take up their positions and the turret captain reports to Control. We then hear “All guns load” and up come the gun-loading cages with a thud and out go the rammers.

The Controller barks “Salvoes” and the right gun is brought to the ready. Then “Enemy in sight” and the sight-setters chant out the range, by which time both guns are almost horizontal because of the close range.

The fire gong sounds “Ding ding,” the right gun fires and recoils as a “woof” rocks the turret. The left gun is brought to the ready as the right gun re-loads.

Sixteen rounds have been fired in the fiord and the targets either sink or blow up. Control issues the order “Check fire” and the gun crews clamber through the manhole at the top of the turret to see the damage.”

The German High Command revealed later that a second submarine ordered to torpedo the British battleship ran aground whilst submerged and took no further part in the battle.

After a further bombardment of Narvik port, Warspite sailed for Alexandria and arrived on 10 May 1940 to become the flagship of Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham.

When Italy entered the war in June, Cunningham’s fleet carried out a sweep of the central Mediterranean, guarded convoys taking ammo and stores for Wavell’s campaign in Egypt and dodged high-level bombing by Italian aircraft.

Finding the battleship Giulio Cesare off the port of Calabria, Warspite scored a direct hit at a range of 26,000 yards. It was the longest-range gunnery hit on a moving target ever recorded and the Italian ship was put out of action for the rest of the war. The other Italian warships with her turned tail and sped away.

The “Grand Old Lady” (who was given her nickname by Admiral Cunningham) next supported the Eighth Army by shelling enemy fortifications along the coast at Bardia, Fort Capuzzo and Tripoli.

By early 1941 the Nazis realised that the Italians no longer had the heart to fight and sent their own air and ground forces to the Mediterranean. But not before the Italian Navy was caught at night by Cunningham’s fleet off the Greek coast at Cape Matapan. During the action, three Italian heavy cruisers and two destroyers were sunk in a barrage lasting less than five minutes.

Chief Petty Officer Jones reports:

22.25.30 Enemy in sight on Warspite’s starboard side.

22.27.15 Turrets loaded, ready and on target.

22.27.55 We open fire with broadsides.

22.28.00 Hits secured on first cruiser, which bursts into flames along its full

length.

22.28.40 Second broadside fired on same target, now sinking.

22.29.18 Third eight-gun broadside fires at next cruiser, which also bursts

into flames.

Such were the fruits of the Royal Navy’s gunners constantly practising night-fighting during peace time.

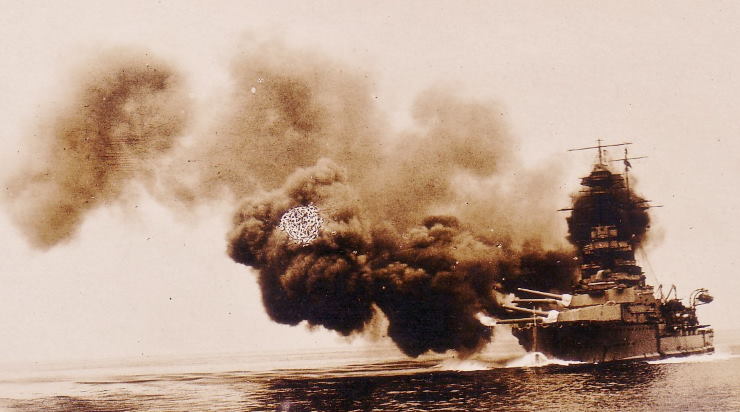

On 21st April 1941 Warspite opened fire with her 15-inch and 8-inch batteries on the quays and ships in Tripoli harbour, causing great damage. She was then engaged in convoy work and survived heavy attacks by the Luftwaffe due to the terrific anti-aircraft barrage put up by the fleet – but she was not so lucky when covering the evacuation of British troops when the Germans attacked Crete.

Cunningham’s entire fleet was again bombed and machine-gunned by German planes, and Warspite was hit by a 500 lb armour-piercing bomb on the starboard side forward where C.P.O. Jones had been standing one minute before while he was repairing a jammed ack-ack gun.

The 4-inch guns and all the gunners were blown overboard and the explosion started a fire that put all four 6-inch guns out of action. One boiler-room had to be abandoned and the ship’s speed was considerably reduced.

An officer and 37 men were killed and 31 others wounded. My father commented: “Had I not been ordered back to my turret to load up I would certainly have been among the casualties.”

He was mentioned in dispatches “for gallant and meritorious action in the face of the enemy” and awarded oak leaves that were sewn on his medal ribbon.

Warspite limped back to Alexandria and was patched up before sailing to have major repairs done at the Bremerton Navy Yard in Seattle, USA, where my father and other crew members left her and were posted to other ships. He served in HMS Resolution until October 1941 and then returned to the home and family he had not seen for four years and four months.

“That’s the luck of the Navy,” he observed. “But at least I got back alive.”

Although serving in other ships, he followed Warspite’s fortunes until the war ended. She was repaired and ready for service again by January 1942, by which time America was in the war. After taking part in the Sicilian campaign in January 1943, Italy surrendered and she led the surviving ships of the Italian fleet into captivity in Malta.

Warspite was bombed again in Salerno and, after more repairs, was in action on D-Day on 8 June 1944, then several other actions off the French coast.

When Germany surrendered in May 1945 the Admiralty decided that the “Grand Old Lady” should be scrapped after 30 years in service.

It was ironical that on 19 April 1947, while being towed by two tugs to an ignominious end in the Scottish ship-breakers’ yard, a mighty storm arose and a turbulent sea freed the proud old warrior from her captors.

An old Cornish man who witnessed the end of the battleship described the scene: “Aye, the old Warspite do lie there pointing towards Prussia Cove. I mind the night she came in, broadside-on and terrible to see. There was a high wind and powerful seas, and none could hold her. She took the ground close by and then, on the next high tide, she lifted again and was driven onto the rocks in the cove.”

The remaining parts of her hull disappeared forever in 1955 and a memorial stone was unveiled in 1992 near her final resting place.

Warrant Officer Fred Jones was discharged from the Royal Navy at the end of the war and left England with his wife and three sons in 1946 to become Lt. Jones, gunnery instructor of the South African Navy, based in Cape Town.

The “Old Salt” who was aged 36 when he survived the German bombing of Warspite in 1941 died of pneumonia in Grey’s Hospital, Pietermaritzburg, just three weeks before his 91st birthday in August 1996.

Dick Jones, now aged 86, is a former night editor of “The Natal Witness”.

Published: 19th November 2020.