On 17th December 2017, a memorial was unveiled to mark the worst civilian disaster of World War II. It also represented the greatest single loss of life on the tube system, but curiously didn’t involve a train or vehicle of any description. On 3rd March 1943, an air-raid warning sounded and locals raced for cover at Bethnal Green tube station. Confusion and panic conspired to trap hundreds on the staircase entrance. In the crush that ensued, 173 were killed including 62 children with over 60 injured.

My Mum was 16 years old at the time; her education long since curtailed, she was working in a factory bottling disinfectant. The family home was at 12 Type Street, a five minute walk from the tube station. People were initially banned from using the tube to shelter from air raids. Authorities feared a siege mentality and disruption of troop movements. So people had to rely on conventional brick buildings or the woefully inadequate Anderson shelters. Rules were eventually relaxed as the tube became a safe haven for thousands of Londoners. Bethnal Green tube was built in 1939 as part of the Central Line eastern extension. It soon became a subterranean environment with a canteen and library serving residents. People bickered over the best spots like tourists fighting over a sunbed. Weddings and parties were commonplace as the tube quietly worked its way into people’s daily routine. Dinners were half eaten and bodies half washed when the siren went off and everyone bolted for the tube.

The picture above shows just how relaxed and comfortable people felt on the underground. My Mum is in the centre eating a sandwich; to the left, looking unbearably cool in a turban is my Aunt Ivy; while on the right, knitting needles in hand is my Aunt Jinny. Just behind Mum to the left is my Nanny Jane. Grandad Alf (not in picture) was a veteran of the Great War, but with lungs wrecked by a gas attack was unable to serve in WWII. He was instead employed as a carman on the London, Midland and Scottish Railway.

The weather had been surprisingly mild for March, although it had been raining that day. The Blitz had finished a year previously, but the allies had bombed Berlin and reprisal attacks were expected. That evening, Mum and her two older sisters sat down for supper at 12 Type Street. At 8:13pm the air-raid warning sounded; Nanny looked to the patriarch for guidance. Grandad drew breath and said “no I think we’ll be alright, let’s stay up tonight”. This display of bravado can only be described as a fateful decision. I can’t help but wonder if he saved everyone’s life that night, and the lives of seven grandchildren and ten great grandchildren that followed?

But something wasn’t right; anyone who experienced the Blitz recognised the same pattern. After the siren came a short pause followed by the ominous rumble of plane engines, and then the whistling terror of bombs descending – but this time nothing? But then suddenly a thunderous salvo that sounded similar to bombs but without the planes overhead? Minutes felt like hours as everyone sat tight waiting for the all clear. Then a knock at the door; there had been a crush on the tube and people had been hurt. Grandad told everyone to stay put as he rushed off to help in the rescue. Anxious relatives scurried from house to house, desperate for news of their loved ones; hoping for the best but fearing the worst. My Grandad was the second youngest of 13 children, which meant Mum had around 40 first cousins living in the surrounding area, one of whom, George had just returned home on leave. He was told his wife Lottie and their three year old son Alan had gone down the tube. Having not seen his wife and child for several months, he excitedly ran to catch them up. Grandad returned home in the early hours exhausted by the carnage he had witnessed; a grim reminder of the Great War made worse by the knowledge that George, Lottie and Alan were among the victims.

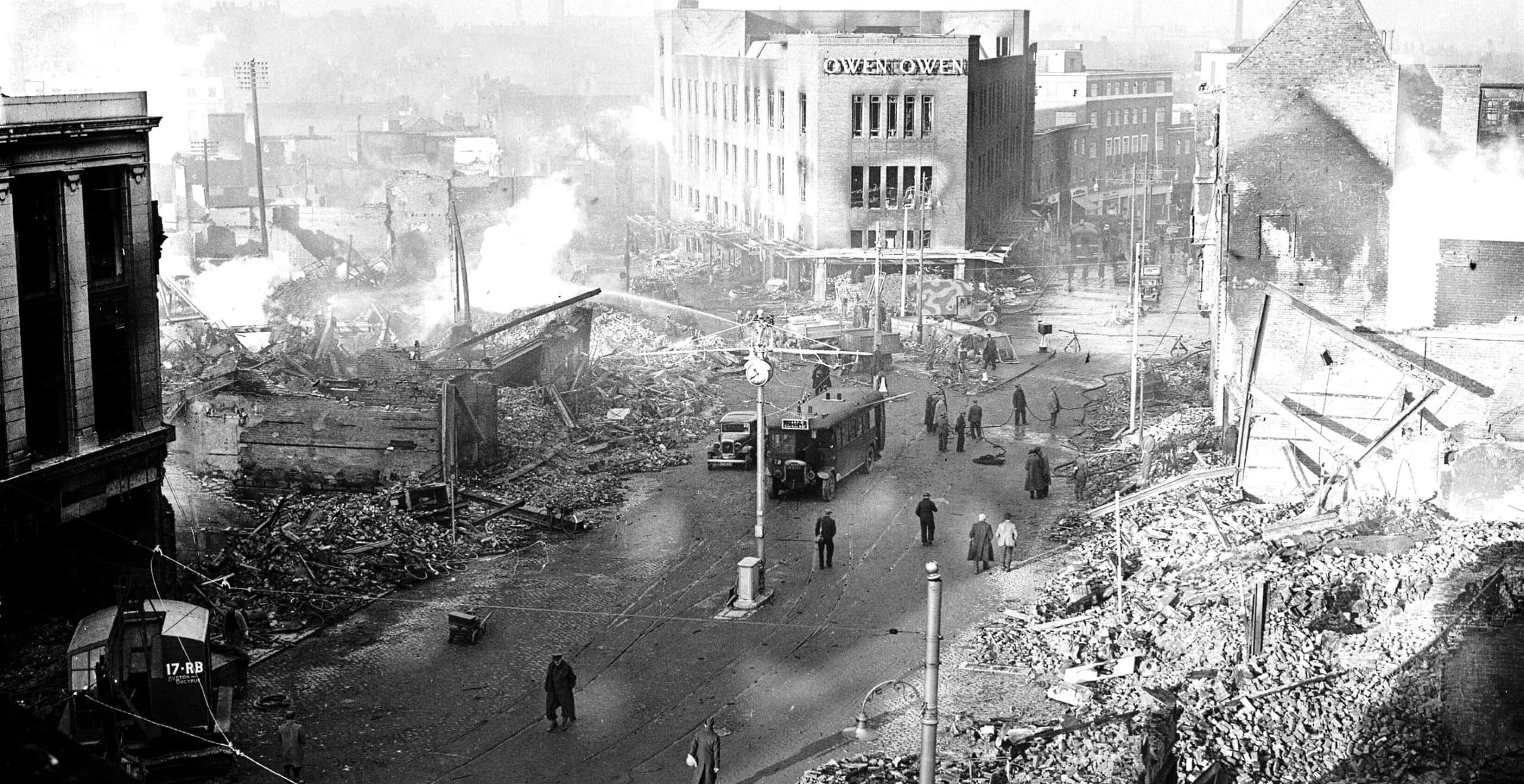

The full scale of the tragedy became clear in the days that followed, but the true cause was kept secret for another 34 years. Early reports suggested the tube station had been hit by enemy aircraft. However, there was no air-raid that night nor were any bombs dropped. The truth would be a massive blow to morale and give the enemy comfort, so the council kept quiet to maintain the war effort.

With the warning siren in full effect, hundreds were streaming towards the entrance; they were joined by passengers alighting from buses nearby. A woman carrying a young baby fell; an elderly man tailgating tripped over her with the inevitable domino effect. The momentum of those behind carried them forward as a sense of urgency turned into naked fear. People were convinced they heard bombs falling and pushed even harder to find cover. But why were Blitz hardened Londoners unduly disturbed by such a familiar sound?

The answer can be found in the secret testing of anti-aircraft guns in nearby Victoria Park. People felt that they were under attack from a new weapon of destruction. The authorities had made a catastrophic miscalculation; they assumed people would treat the test as a routine air-raid and file calmly into the tube station as normal. But the unexpected ferocity of gun fire caused people to panic. Surprisingly, no policemen were on duty at the entrance. There were no central hand rails on the stairway, nor was there sufficient light or marking of steps. Two years before the disaster, the council had asked if they could make alterations to the entrance but were denied funds by the Government. Typically, handrails were installed and steps painted white after the incident.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing but events of that night were reasonably foreseeable. Conspiracy theories still do the rounds, but just occasionally the truth is more compelling. Frailties of the human condition were there for all to see; it was just one assumption too many. As the disaster slips from living memory, it is even more important to mark the event.

In 2006, the Stairway to Heaven Memorial Trust was set up to erect a memorial in tribute to those who died. The unveiling ceremony was attended by special guests including the Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan. It was finally vindication and recognition of the errors made. The memorial is long overdue and a refreshing change from the usual statues and plaques; instead, an inverted staircase overlooks the entrance with the names of victims carved into each side. With memorials appearing on every other street corner, it’s tempting to let another pass by unnoticed. But to neglect the past betrays the lessons we can learn from history.

All photographs © Brian Penn

Brian Penn is an online feature writer and theatre critic.