On 27th August 1816, the coastal city and capital Algiers was bombarded by an Anglo-Dutch fleet under the command of Admiral Edward Pellew, 1st Viscount Exmouth. The goal was simple, to end the white slavery practised by the Dey of Algiers and restore the captives back to their homeland in Europe.

Almost one hundred years earlier, a young boy by the name of Pellow experienced this enslavement first-hand. The twelve year old boy from a small coastal community in Cornwall had joined his uncle’s vessel when one fateful day they encountered Moroccan corsairs who took all the men aboard, including young Thomas Pellow back to Morocco for a lifetime of servitude and imprisonment.

His story would eventually become a famous one, relayed in his own autobiographical account detailing his intrepid survival skills, forced conversion to Islam and eventual escape several years later.

Despite his ordeal, Thomas Pellow could be considered one of the lucky ones: several of his European compatriots not only never escaped their enslavement but died through torture, hard labour or simple execution at the hands of their overlords.

This practice was widespread across North Africa, with one of the most formidable Sultan Moulay Ismail of Morocco being known for his abject cruelty and barbarous techniques.

By the second half of the seventeenth century, hardly anyone on the European coastline had been untouched by the corsairs of North Africa. Hit and run raids on their shores affected a huge range of communities from the small Mediterranean islands to Portugal, France, Spain, Italy and Greece. Further north too, communities in Holland, Wales, Ireland and even Iceland were affected.

Meanwhile, the governments back in Europe were unsure as to how to respond. In some cases representatives were sent to negotiate and buy back as many slaves as they could, however this was no long-term solution and proved quite small-scale considering how many were in captivity.

Over a century later and with the practise still very much in force across North Africa, finally a stand was made and it would come forcefully, led by a man who himself came from Cornwall like Thomas Pellow one hundred years earlier. Admiral Edward Pellew, a man of great renown was in fact an indirect descendant of Thomas Pellow, the man who had escaped his enslavement and lived to tell the tale.

Admiral Pellew was an esteemed British naval officer who had a wealth of experience under his belt, including in the American War of Independence as well as the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars which had defined the careers of his sea-faring generation.

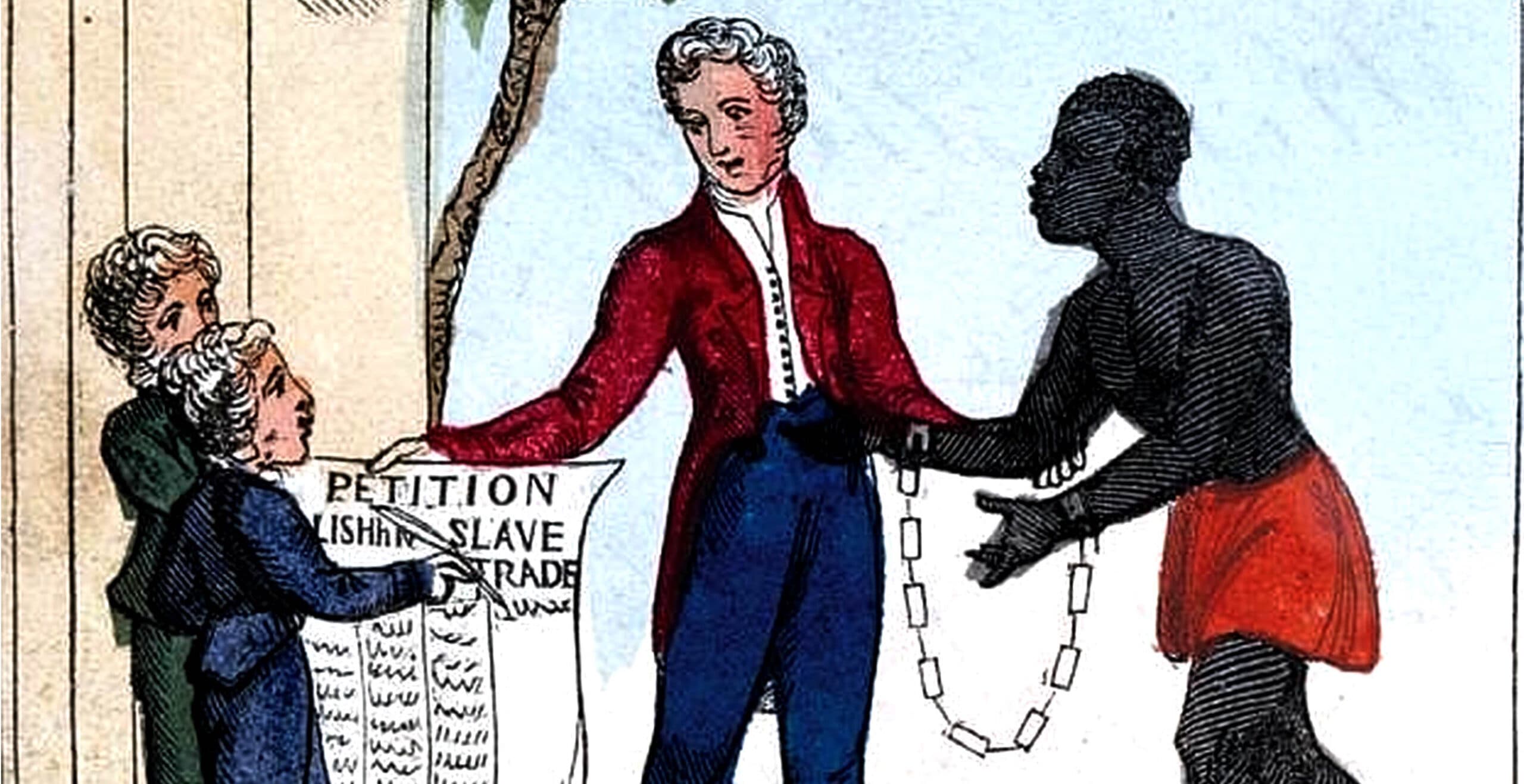

It was in this context that Sir Edward Pellew seemed the perfect man for the job. He had become involved in the endeavour to fight against white slavery through his contact with another admiral, Sir Sidney Smith who had established a movement called the Society of Knights Liberators of the White Slaves of Africa.

When the Congress of Vienna began in 1814 in order to discuss peace after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Sir Sidney had arrange for himself and other delegates to discuss the issue of white slavery and petition for military engagement in order to resolve it once and for all.

With three hundred years of such a practice plaguing European shorelines, Smith felt some tangible and decisive action needed to be taken. Moreover, with the Napoleonic Wars now drawn to a close, the Royal Navy no longer needed to use the Barbary States for supplies to Gibraltar and their stationed fleet. With the political landscape now changed in Europe, Britain was free to engage more overtly.

That being said, at the Congress of Vienna a resolution was passed in condemnation of the act of white slavery, however with no proposal to put into action.

Sir Sidney left demoralised, however it soon became apparent that his impassioned pleas for action had not fallen on deaf ears and were in fact heeded particularly in southern Europe where communities were most affected.

In reaction, Britain’s foreign secretary Lord Castlereagh received a backlash from the southern European leaders for his inaction and as a result he began setting plans into motion.

Meanwhile, Sir Edward Pellew was invited by Sir Sidney to join the Society of Knights Liberators which he enthusiastically accepted.

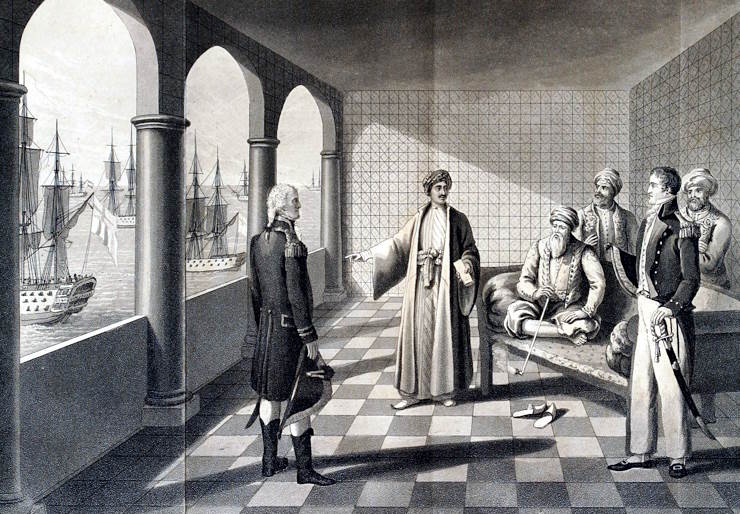

In early 1816, Pellew’s initial task was a diplomatic mission to Tunis, Algiers and Tripoli with a modest squadron in order to convince the leaders to end their practise of white slavery. In response, both Tunis and Tripoli seemed to acquiesce to his demands with little or no coercion, however the Dey of Algiers proved a more difficult opponent to win over.

That being said, Pellew ended his negotiations believing he had achieved an agreement and returned to England. This was not however as smooth sailing as it first appeared, as some Algerian troops ended up killing 200 fisherman of Corsican, Sicilian and Sardinian origin. This event took place just after the treaty was signed and thus caused outrage as it appeared to immediately void the peace talks. Thus the stage was set for a more volatile encounter.

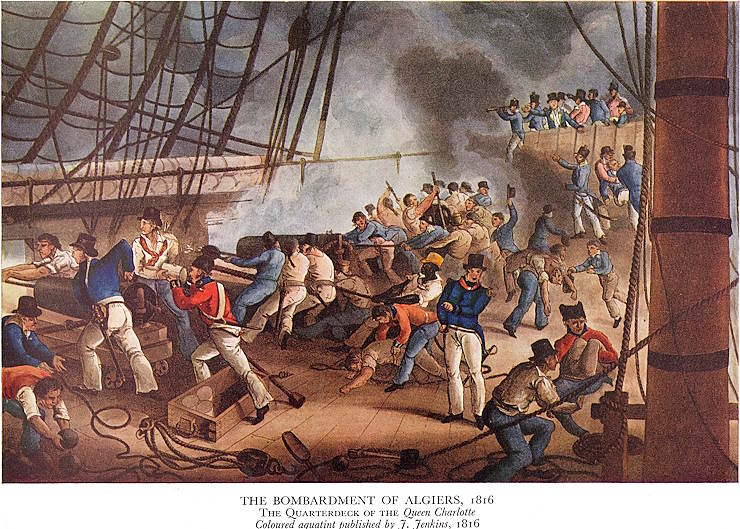

By the end of August a fleet had been organised consisting of five ships, four frigates and four bomb ships with HMS Queen Charlotte as flagship with 100 guns. There were also an additional five sloops, eight ships, boats with rockets and transportation for the rescued slaves. Moreover, Dutch forces had offered their services, bolstering the main fleet with an additional squadron of Dutch vessels.

With the flagship Queen Charlotte anchored in the bay of Algiers facing the Algerian guns, Pellew gave his ultimatum to the Dey of Algiers to give in unconditionally within an hour and surrender his slaves.

Whilst both leaders agreed neither would fire the first shot, around 3pm from the direction of the shoreline, an Algerian fired one single shot. The battle now ensued.

In response Pellew gave his signal to his captains and as he did, the billowing sound of gunfire echoed around the bay.

Queen Charlotte tilted as she launched twenty-four pounders from one side of the warship towards the city’s defences. What followed was the unleashing of guns firing 300 musket balls at the corsairs.

Meanwhile the Algerian flotilla, consisting of around 40 gunboats, attempted to board the Queen Charlotte but the British were able to take out 28 of these boats with the rest escaping to shore.

The Algerians however proved to be formidable opponents, as they equalled gunfire towards Pellew’s fleet leading to numerous casualties. Moreover, they employed the use of snipers whose task it was to take out Pellew with the aim of his death dealing a devastating blow to the morale of his crew.

Fortunately for Pellew, he survived two musket shots which went through his clothing and another which damaged his telescope. The injuries he did sustain came from a large splinter of wood which had flown through the air and imbedded itself into his jaw.

On the Algerian side, people were forced to dive for cover as the unrelenting ammunition was raining down on the city with the fleet discharging hundreds of cannon-balls into numerous targets.

Fierce fighting continued for hours with the Algerians managing to do enormous damage to the fleet, disabling the rigging and sails and amassing huge casualties; as one lieutenant noted “the slipperiness of the decks, wet with blood”. In particular, the vessel Impregnable was in an isolated position which made her a prime target, allowing the Algerians to cause severe damage.

Undeterred, the Anglo-Dutch fleet now turned its attentions to the corsair fleet in the harbour and launched a barrage of gunfire destroying several vessels and setting the port ablaze.

Fighting would continue well into the night when finally a brief respite appeared, when the Algerians could not maintain their fire and at around 10pm Pellew decided to weigh anchor, leaving HMS Minden to keep firing whilst Queen Charlotte sailed out of range.

By this time, the amount of firepower used amounted to around 50,000 cannon-balls, causing absolute devastation to the city of Algiers.

By the early hours of the morning the damage on both sides was being surveyed. The Algerians had witnessed much of the city destroyed whilst the flames from the port were fanned by the wind towards the city.

Meanwhile, the British took this time to clear up the damage on their ships and treat their wounded.

When morning came Algerians woke up to the destruction of their beloved city, as well as the grim sight of bodies floating in the water, many of whom were corsairs. With a high death toll and the city unrecognisable, the Dey of Algiers received a letter from Sir Pellew at noon, restating the same demands he had made before engaging in battle and with the additional caveat that if he resisted such terms, the battle would resume.

With the Dey of Algiers surveying the damage, he was left with no option but to accept and agree to all terms unconditionally which included releasing his captives and ending the slave trade.

As such, this agreement in total would lead to around 1,200 slaves being released and roughly 3,000 slaves being freed over a longer period of time. A treaty was also signed against the enslavement of Europeans.

Sir Edward Pellew was met by the freed slaves who despite their poor condition, greeted him in a state of ecstasy.

On his return home he was given a hero’s welcome, celebrated and given honours by other European nations and even the Pope, who all recognised the magnitude of his achievement.

That being said, whilst the bombardment of Algiers proved victorious for the British, time would tell whether the treaty would hold water. In reality the slave trade would continue to be practised until the French invasion of Algiers in 1830.

Nevertheless, the victory in 1816 in Algiers was much more symbolic as it gave hope that after centuries of being the victims of raids and kidnappings, one day the fishermen of Europe would no longer have to fear the pirates of North Africa.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 28th October 2024.