The inhospitable terrain, the unforgiving and unpredictable weather, fractured tribal politics, turbulent relations with the local population and armed civilians: these are just some of the issues that led to Britain’s downfall in Afghanistan.

This refers not to the most recent war in Afghanistan (although you would be forgiven for thinking so), but Britain’s humiliation in Kabul almost 200 years ago. This epic defeat happened during the very first Afghan war and Anglo-invasion of Afghanistan in 1842.

It was a time when the British colonies, and indeed the East India Trading Company, were extremely wary of Russian power-expansion in the East. It was thought that a Russian invasion of Afghanistan would be an inevitable part of this. Such an invasion was of course finally realised more than a century later with the Soviet-Afghan war of 1979-1989.

This period in the 19th century is something historians refer to as the ‘Great Game’, a tug of war between East and West over who would control the region. Although the area remains in contention even to this day, the very first Afghan War was not so much a defeat for the British, as it was a complete humiliation: a military disaster of unprecedented proportions, perhaps only matched by the Fall of Singapore exactly 100 years later.

In January 1842, during the First Anglo-Afghan War, while retreating back to India, the entire British force of around 16,000 troops and civilians was annihilated. Until this point the British military and the private armies of the East India Company had a reputation all over the world of being incredibly powerful and a stalwart of British efficiency and order: a continuation of this success was expected in Afghanistan.

Fearful of increased Russian interest in the area, the British decided to invade Afghanistan and marched unchallenged into Kabul in early 1839 with a force of approximately 16,000 to 20,000 British and Indian troops collectively known as Indus. Yet a mere three years later there was only one known British survivor who staggered into Jalalabad in January 1842, after fleeing the carnage that befell his comrades in Gandamak.

The occupation in Kabul had begun peacefully enough. The British were originally allied with the indigenous ruler Dost Mohammed, who over the preceding decade had succeeded in uniting the fractured Afghan tribes. However, once the British began to fear that Mohammed was in bed with the Russians, he was ousted and replaced with a more useful (to the British anyway) ruler Shah Shuja.

Unfortunately, the Shah’s rule was not as secure as the British would have liked, so they left two brigades of troops and two political aides, Sir William Macnaghten and Sir Alexander Burns, in an attempt to keep the peace. This was however not as simple as it seemed.

Underlying tensions and resentments of the occupying British forces bubbled over into full-on rebellion by the local population in November 1841. Both Burns and Macnaghten were murdered. The British forces that had elected not to remain in the fortified garrison within Kabul but instead in a cantonment outside of the city, were surrounded and completely at the mercy of the Afghan people. By the end of December, the situation had become perilous; however the British managed to negotiate an escape to British-controlled India.

With the rebellion in full force it is perhaps surprising that by these negotiations the British were in fact allowed to flee Kabul and head to Jalalabad, around 90 miles away. It may be that they were allowed to leave purely so that later they could become victims of the ambush at Gandamak, however whether this is the case or not is unknown. Exact estimates of how many people left the city differ, but it was somewhere between 2,000 and 5,000 troops, plus civilians, wives, children and camp followers.

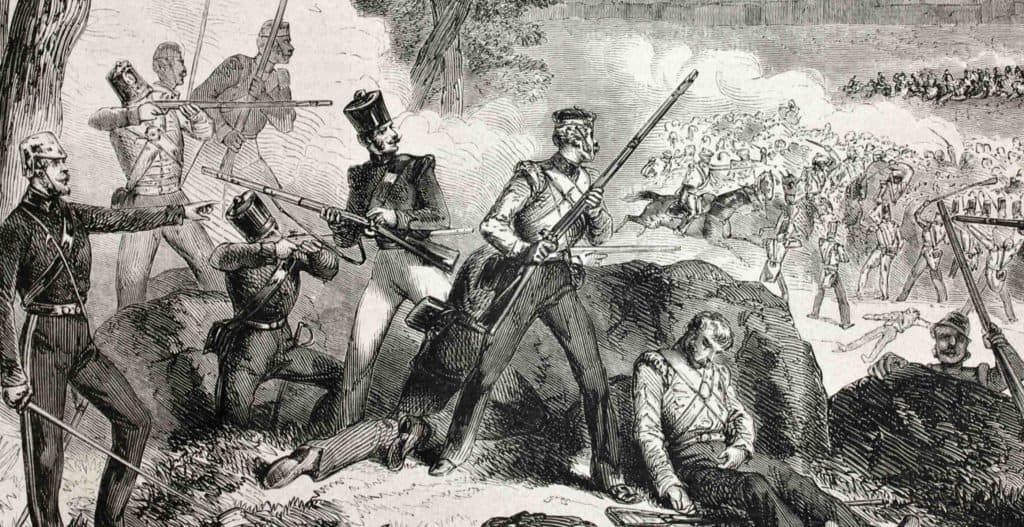

Around 16,000 persons eventually evacuated Kabul on January 6th 1842. They were led by the commander-in-chief of the forces at the time, General Elphinstone. Although undoubtedly fleeing for their lives, their retreat was not easy. Many perished from cold, hunger, exposure and exhaustion on the 90-mile march through the perilous Afghan mountains in horrendous winter conditions. As the column retreated they were also harried by Afghan forces who would shoot at people as they marched, most of whom were unable to defend themselves. Those soldiers that were still armed attempted to mount a rear-guard action, but with little success.

What had begun as a hasty retreat quickly became a death march through hell for those fleeing as they were picked off one-by-one, despite the treaty allowing them to retreat from Kabul in the first place. As the Afghan forces increased their attack on the retreating soldiers, the situation finally spiralled into a massacre as the column came to the Khurd Kabul, a narrow pass some 5 miles long. Hemmed in on all sides and essentially trapped, the British were torn to pieces, with over 16,000 lives lost in a matter of days. By January 13th everyone, it seemed, had been killed.

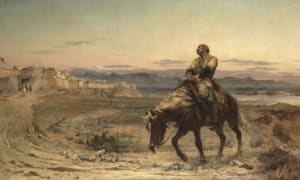

In the initial bloody aftermath of battle, it appeared that only one man had survived the slaughter. His name was Assistant Surgeon William Brydon and somehow, he limped into the safety of Jalalabad on a mortally wounded horse, watched by those British troops who were patiently waiting for their arrival. Asked what had happened to the army, he answered “I am the army”.

The accepted theory was that Brydon had been allowed to live in order to tell the story of what had happened at Gandamak, and to discourage others from challenging the Afghans lest they face the same fate. However, it is now more widely accepted that some hostages were taken and others managed to escape, but these survivors only began to appear well after the battle had finished.

What is undeniable however is the absolute horror that befell those retreating British soldiers and civilians, and what a grisly bloodbath that final last stand must have been. It was also an utter humiliation for the British Empire, who withdrew completely from Afghanistan and whose reputation was severely tarnished.