On 31st July 1916, the British Prime Minister Herbert Asquith gave a statement in the House of Commons:

“I deeply regret to say that it appears to be true that Captain Fryatt has been murdered by the Germans. His Majesty’s Government have heard with the utmost indignation of this atrocious crime against the laws of nations and the usages of war.”

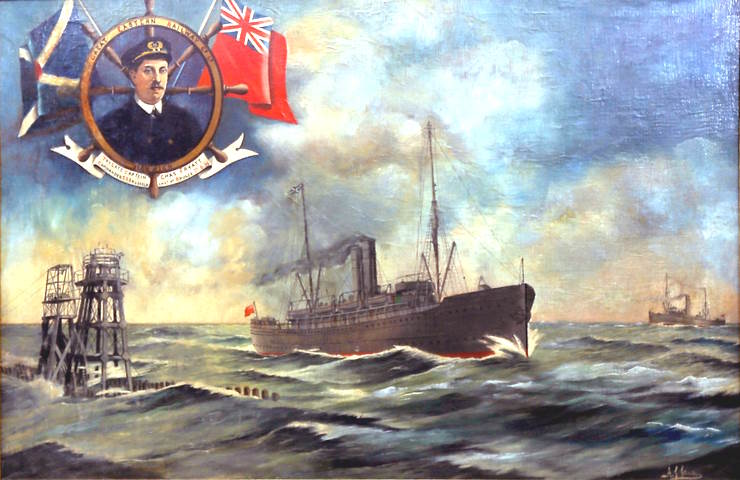

The man to whom he was referring was Charles Algernon Fryatt, Captain of the passenger ferry SS Brussels, who had been brutally executed at the hands of the Germans only four days earlier.

As the second British civilian (Nurse Edith Cavell was the other) to be executed in the war, his death caused a public outcry.

The story of Fryatt’s life begins back in Southampton where he was born in December 1872. Shortly afterwards his family moved to Essex from where Charles would leave school to attend the Mercantile Marine.

By 1892 he had joined the Great Eastern Railway (the company acquired Parliamentary powers to operate steamers in 1863), as a seaman on the SS Ipswich, following in his father’s footsteps.

Whilst serving on board numerous vessels, Fryatt proved himself a competent and capable seaman and was thus promoted, so by the time the war broke out he was master of the SS Newmarket.

Whilst his career went from strength to strength, so too did his personal life as he married a woman called Ethel and went on to have seven children, six girls and one boy.

With the outbreak of the First World War however, Charles Fryatt’s job was about to become much more dangerous. The perils of merchant shipping were to become evident as in February 1915 the German government declared that any such ships could and would be attacked without warning.

Such examples were to follow as the SS Wrexham, which was under Fryatt’s command, came under fire from a German U-boat and was pursued towards the port of Rotterdam, forcing the ship to make 16 knots when really its capacity only allowed 14 knots, such was the threat. By the time they had arrived safely in the port of Rotterdam, upon inspection the funnels were burnt.

In gratitude for the enormity of the effort to keep SS Wrexham safe from the German pursuit, Fryatt was awarded a gift by the Great Eastern Railway in recognition of his leadership and bravery.

Unfortunately not all vessels were so fortunate, as a month later the steamship RMS Falaba was sunk by the Germans, leading to the death of 104 civilians.

On that same day in March 1915 Fryatt, now captain of the SS Brussels, was approached by a German U-33 submarine and given orders to stop. The SS Brussels was a passenger ferry that ran between Harwich and neutral Holland.

With the U-boat clearly intent on torpedoing his ship, Fryatt followed the orders given by Winston Churchill (First Lord of the Admiralty at the time) which was for captains of merchant ships to treat the Germans as criminals rather than prisoners of war. The captain was obliged to evade surrendering his ship to the Germans at all costs, or else face prosecution by the British.

Heeding the sentiment of this policy, Fryatt ignored the U-boat request and went full steam ahead in an attempt to ram the U-boat, forcing the submarine to subsequently crash-dive in response to this head on collision.

In recognition of his efforts against the Germans, Fryatt was given a gold watch by the Admiralty. His courage was also noted in the Houses of Parliament, on both sides of the house, his courageous stand against enemy incursions respected and celebrated by politicians from all parties.

After the drama of his most recent journey, all returned to normal for Fryatt who simply resumed his duty and carried on as captain, going to and from the Dutch and British ports.

In the coming months, British merchant ships would come under further attacks by U-boats as the German policy of attacking civilian ships continued.

A year later on 22nd June 1916 SS Brussels, commanded by Fryatt, set sail from the Hook of Holland, England-bound with food supplies as well as Belgium refugees fleeing to safety.

Just as the ship left Dutch waters it found itself surrounded by five German destroyers, giving orders for the ship to stop. The vessel was then boarded by the Germans and taken to Bruges which was in occupied territory held by the Germans.

The passengers boarded the lifeboats and destroyed their papers, whilst the Germans took SS Brussels and destroyed its radio before taking it to Bruges.

Captain Fryatt and his crew were taken to Ruhleben, which was a civilian internment camp.

Whilst being held there, the German vendetta became clear. Fryatt was the man they wanted, and now that they had him, their revenge would play out for the world to see.

A few weeks after the ship’s capture, on 16th July it was revealed by a Dutch newspaper that Fryatt had been formally charged with the sinking of the German submarine. Whilst the U boat had in fact not been destroyed by his action, the intent to cause damage to the submarine was enough. The inscribed watch, a reward from the Admiralty, was used as evidence for Fryatt’s condemnation, despite his civilian status.

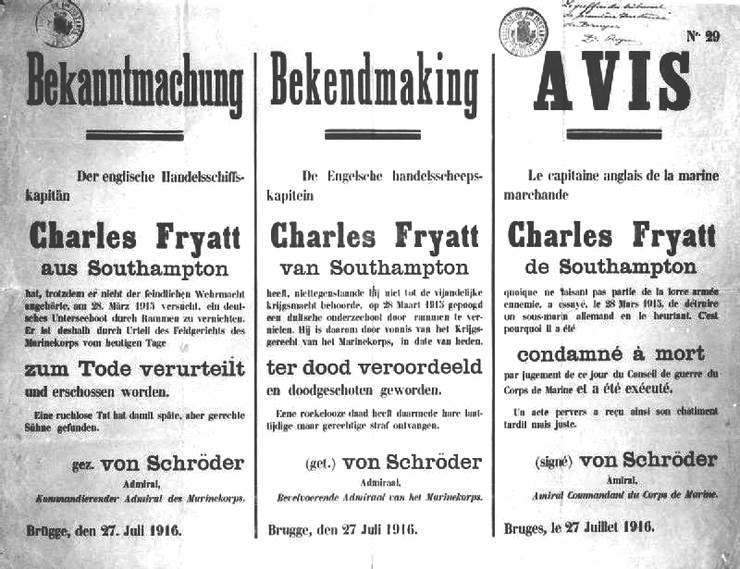

On 27th July 1916, Fryatt appeared in Bruges Town Hall where he was court-martialled by the Imperial German Navy and found guilty of being a franc-tireur (a civilian shooter/engaged in military action). His punishment was death.

The sentence was carried out that same night at 7pm and witnessed by the town’s Alderman. News of his execution by the naval firing squad in the Jardin de l’Aurore soon spread.

The official confirmation that followed came from a telegram sent by the American Ambassador to the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Grey.

Charles Fryatt, a captain and merchant seaman, died as a civilian executed by the German Navy, leaving behind a widow and seven children.

The notice that followed was subsequently published in three languages and signed by Admiral Ludwig von Schröder.

Charles Fryatt’s body was taken to a cemetery on the outskirts of the city which had been designated for civilians who had engaged in such offences.

The backlash which followed the notice was widespread, international and came from the highest echelons of public and political office, not to mention the condemnation from the wider general public upon hearing the tragic news.

Only a few days after the execution, the British Prime Minister Asquith gave a statement of condemnation in the House of Commons, citing the execution as a crime which flouted all international law, whilst the First Lord of the Admiralty, Arthur Balfour described it as a judicial murder.

Meanwhile, the King also expressed his sorrow and abhorrence at his execution describing his actions as “noble” and “characteristic of his profession”.

A week later in the centre of London, crowds gathered in Trafalgar Square to show their indignation at the callous murder of Fryatt. This condemnation also included a statement from his wife, demanding that those guilty of his murder be punished.

In response to the public outcry, the War Cabinet considered the confiscation of German property in the United Kingdom as a response.

Meanwhile, Lord Claud Hamilton, Chairman of the Great Eastern Railway and Member of Parliament denounced it as a “brutal murder” whilst the Mayor of Harwich put together a fund in order to create a memorial.

Likewise in the Netherlands, Fryatt’s memory was also recognised with a memorial.

News of his death hit the headlines in the international press, eliciting much the same reaction of fury, condemnation and outcry against this senseless murder.

In the Netherlands it was described as “arbitrary and unjust” whilst in New York, the Herald described it as “the crowning German atrocity”.

Sadly, any such condemnation was not enough for his widow back home, who now had seven children to take care of, a plight which was recognised by the authorities.

In response, the Great Eastern Railway set up a national memorial fund and raised a widow’s pension of £250 per annum.

In addition, the government, in recognition of her husband’s bravery and ultimate sacrifice, gave her an extra amount of £100 on top of her basic amount. Mrs Fryatt would also receive the £300 of life insurance she was due from the insurers much quicker than was usual, given the high-profile nature of this particular case.

Meanwhile, the Royal Merchant Seaman’s Orphanage offered educational services to two of her children.

Such assistance both financial and educational would prove vital for the survival of the Fryatt family.

Three years later, an international commission called the Schücking Commission ruled that his execution had been legal within the framework of international law and stipulated that only the speed at which the sentence had been commuted was regrettable.

Whilst the commission was not unanimous, those guilty of his death would never be held to account.

Once the war was over, it was only right that Captain Fryatt should be given a formal burial in England, one that would garner much attention from the general public and be attended by the Prime Minister and the entire War Cabinet.

The state funeral took place in July 1919, with military escorts and the streets lined with mourners paying their last respects.

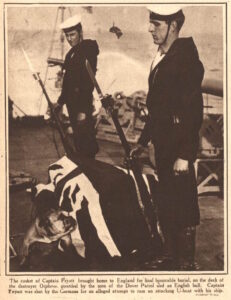

His body had been transported from Bruges and taken on board the HMS Orpheus to the port of Dover. His coffin, draped in the Union Jack was then taken aboard a train to Charing Cross where it was subsequently placed on a gun carriage and given an escort for its journey to St Paul’s.

The formality of arrangements and use of military escorts demonstrated the significance of Captain Fryatt’s sacrifice and illustrated the importance of being given a respectful final resting place.

Captain Fryatt had been a normal man simply doing his job when he was executed in cold blood. His story and those like him, would demonstrate the grim reality of war and the ultimate sacrifice that was paid.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 15th October 2023.