Fourteen years before the Balfour Declaration of 1917, which set out the commitment by a British government to help facilitate the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, a lesser known event took place at the Colonial Office. Two men had been wrestling with their own particular problem but it seemed that a common solution might have been found. The older man, an adopted son of Birmingham, had been a radical Mayor and was now an MP as well as in the Cabinet. The other, twenty five years his junior, was a Birmingham born businessman and activist in a new political movement.

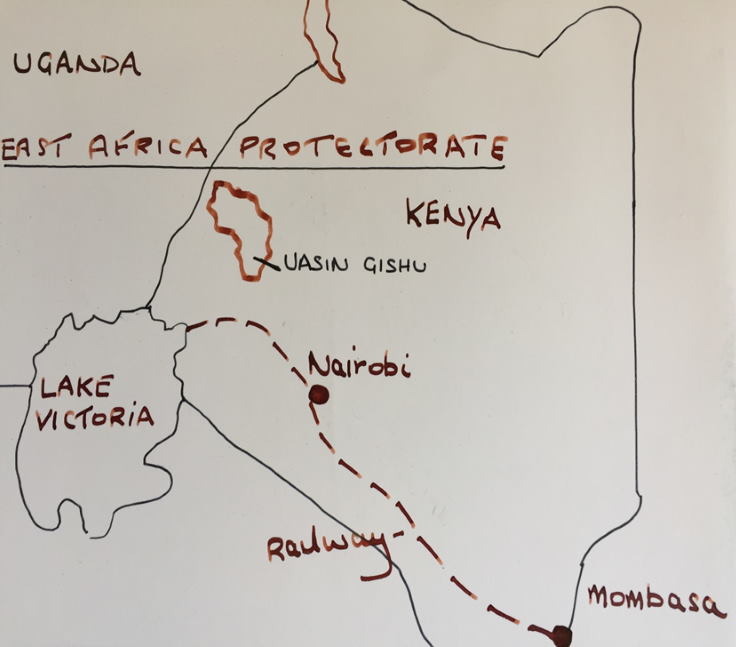

In 1896 despite facing considerable outright opposition, the British government agreed to fund the construction of a railway across its new East Africa protectorate stretching from coastal Mombasa to its final destination almost six hundred miles away, Lake Victoria. Holding the source of the Nile was seen as crucial to protect British interests along the river to the Egyptian coast. Joseph Chamberlain, Colonial Secretary had been a prominent advocate for the construction of the railway which cost £5.5m. In addition to military and security justifications, it was envisaged that settlers from Britain would migrate there to farm and trade, thus generating tax revenues which would contribute to recovering the hefty financial outlay.

However, by 1902 the incomers had not arrived in anything like the numbers anticipated and the consequent level of economic activity was disappointingly low, one critic describing the railway as ‘the lunatic line’. Chamberlain was aware of and sympathetic to the plight of Jews, particularly in Russia where discrimination and violence were commonplace, and believed he had identified a way to improve the prospects for economic activity in the Protectorate whilst also helping to alleviate their suffering.

Five years earlier, a new political movement, Zionism had been formally launched at a congress in Switzerland by a Hungarian Jew named Theodor Herzl. He had concluded that the cause of anti-Semitism was the lack of a ‘Jewish State’ and set out his solution in a pamphlet of that name. The plan was two-fold: to identify and purchase an area of land large enough to accommodate planned mass immigration and, that a charter be secured which gave international legitimacy to the establishment of a state where Jews could live as full citizens, free of discrimination. The resulting Basel Programme committed to work for the creation of such state in Palestine, regarded by many as the historic home of the Jews and therefore the only possible location.

Herzl believed protection from one of the great powers would ensure the security of the new state and saw Britain as the preferred guarantor; but high level discussions would also be held with leaders or their representatives of other European nations and the Ottoman Empire. Despite six years of intense diplomatic activity, by 1903 no meaningful progress had been made and events in Russia led him to review the exclusive focus on Palestine.

Leopold Greenberg, described by Herzl as one of his ‘most able supporters’, had entrusted him with negotiations the previous year when seeking British support for substantial immigration into El Arish on the Sinai coast. However, a survey team reported that the level of irrigation required to sustain the area and the numbers of people moving there, would be detrimental to the many communities reliant on the Nile and negotiations were terminated.

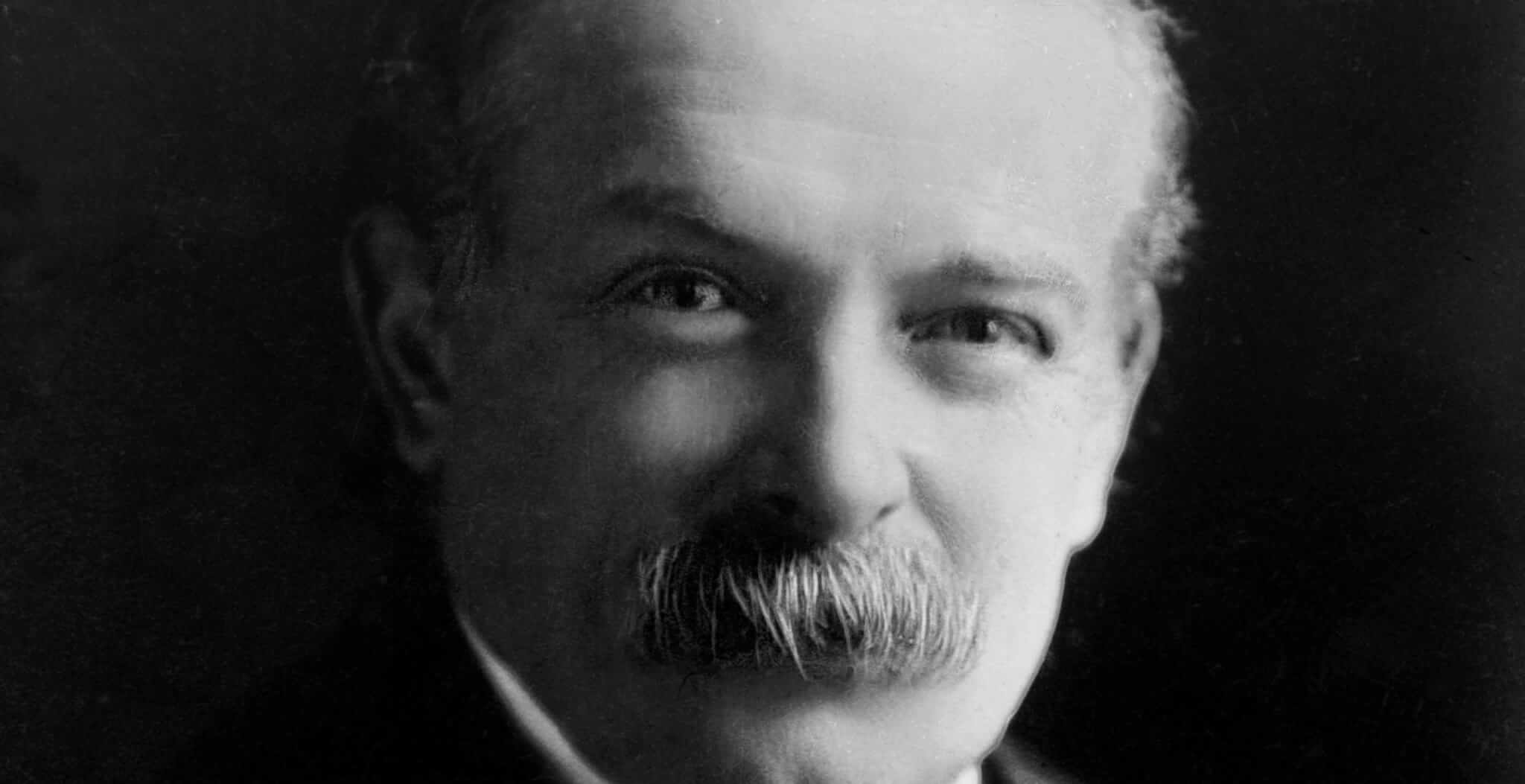

Leopold Greenberg, Businessman and Zionist. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

Leopold Greenberg, Businessman and Zionist. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

That Easter, anti-Jewish pogroms broke out in the city of Kishinev (now Chisinau, Moldova) orchestrated by the local authorities. Forty-nine Jews were murdered, many more injured and property damaged or destroyed. To Herzl and Greenberg it seemed essential to secure somewhere, perhaps anywhere, that could quickly facilitate large scale immigration.

On 20th May, Chamberlain proposed to Greenberg the possibility of Britain making available a tract of land in the interior of East Africa around the Uasin Gishu plateau ‘the most favourable territory between Nairobi and the Mau Escarpment’. The area in question sits in Kenya, but at the time the boundaries of this new East African protectorate had not been finally delineated and the scheme has often been referred to mistakenly as in Uganda.

Chamberlain described the area he had in mind as being on very high ground, benefitting from a fine climate, fertile, ripe for modern agricultural development and capable of supporting at least one million people and crucially, already having access to a railway which could transport produce to the coast. Greenberg was aware that self-government was an essential requirement for the Zionist movement and Chamberlain confirmed that this would be the case. Greenberg pressed the Colonial Secretary further on whether the governor would be Jewish. Once again, Chamberlain agreed.

Another factor which brought the offer into focus was the Royal Commission into Alien Immigration which the British government had instituted in response to growing anxiety following an influx of mainly poor and destitute Jews into the East End seeking refuge. It increasingly seemed that doors to traditional Jewish migration were being closed and that something more structured was needed urgently.

Herzl and Greenberg were only too aware that there would be much opposition from sections of the Zionist movement to the very idea of a land anywhere except Palestine and decided that until any formal offer emerged, all reference to Chamberlain would use the name ‘Brown’.

As agreed with Greenberg, the Colonial Secretary followed up their meeting with a letter confirming the principle of the proposal and Greenberg commissioned a firm of solicitors to prepare a document for consideration. One of those leading the drafting of the charter was a solicitor named David Lloyd George, then a Member of Parliament and later, Prime Minister.

In August, Greenberg presented the formal ‘offer’ in English to the sixth Zionist congress, but immediately faced a major split within the movement. Herzl managed to convince the rebels this would merely be an urgently needed temporary refuge and that Palestine alone was the ultimate objective. In deference to him, Congress agreed to commission an investigation into ‘Brown’s plan’ and a scientific team was, after some delay, despatched to assess soil conditions, climate and the potential for mass Jewish settlement.

Once news of the proposal broke, opposition was also declared by many of the white farmers who had already settled there. The newspaper ‘The African Standard’, most read by settlers, advocated and implemented a campaign of opposition to the very concept. There were also concerns within the Foreign Office that the draft charter presented by the Zionists would in effect create an ‘imperium in imperio’ and argued that it could only ever be a colony.

However, timing was against the whole idea. Shortly afterwards, Chamberlain became embroiled in a battle over tariff preferences and was soon out of government. The following year, Herzl died from a heart condition at the age of forty-four. The expedition duly reported back unfavourably and the offer was subsequently formally rejected at the next congress while careful to thank the British government for their consideration. Greenberg’s efforts to secure a refuge was later described as having ‘no precedent in Jewish history’

For a brief moment, two Brummies came together in an attempt to address specific concerns, but ultimately whether the offer of a self-governing colony in East Africa was ever likely to succeed is questionable. Its demise probably suited both the British government and the majority of Zionists, as well as the relatively few white settlers already there. It also seems plausible to suppose that even if the scheme had come to fruition, the Jewish incomers would have suffered the same fate as the Indian migrants who did settle in East Africa and later fled or were expelled by the post-colonial states of Uganda, Kenya and Zanzibar. A depressing but familiar part of Jewish history might once again simply have repeated itself.

Now in retirement following a career in social housing, William has embarked on researching and writing about one of his life-long interests, modern political history.