Named after a bill called the People’s Charter drafted in May 1838, Chartism was a working class suffrage movement calling for democracy and reform.

Those involved saw themselves as fighting on behalf of industrial Britain and the workers, thus drawing a large swathe of support from communities across northern England but also nationwide, including in the Welsh valleys.

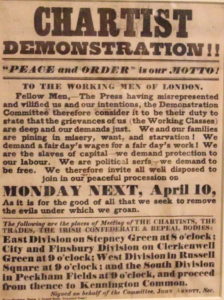

Its aim was to create tangible change through constitutional reform, best summarised through the six demands of the People’s Charter written by William Lovett.

Making up these demands was the call for universal male suffrage, as well as votes by secret ballots and equal electoral districts as the inequalities between constituencies was blatantly undemocratic. Moreover, in terms of political reform, the charter made demands for annual elected Parliaments, payment for MPs as well as abolition of the current property qualifications that were required.

The movement itself lasted for two decades and engaged communities who wanted to fight against what they saw as the inherent inequalities within the political system. They did so largely through peaceful, non-violent and official channels, such as petitions and meetings.

The beginning of this movement could be traced back to the Representation of the People Act in 1832, more commonly referred to as the Reform Act. This was an act passed in parliament that made the first tentative steps in reforming the electoral system. It included within its reforms the extension of the enfranchisement to small landowners, tenant farmers and shopkeepers as well as those who paid a rental of more than £10.

Such qualifications inevitably excluded vast swathes of working men who did not own property and thus agitation for more tangible change ensued.

Whilst the act itself made inroads into extending the franchise, many felt not enough had been done and the actions of the Whig government only appeared to alienate and stoke the fires of the disenfranchised, particularly with the introduction of the Poor Law Amendment in 1834.

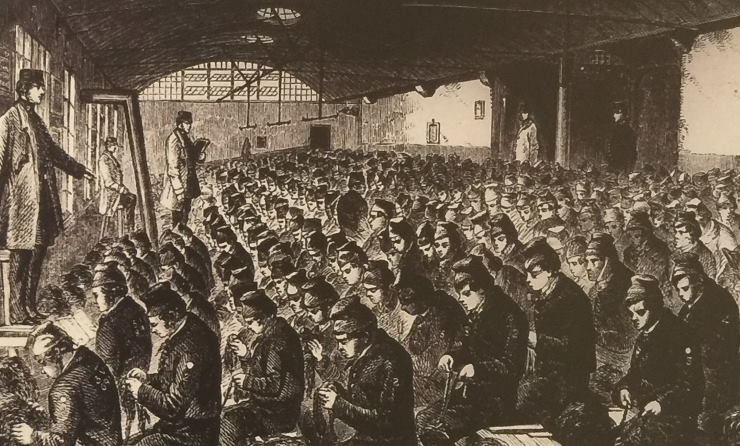

With the legislation being passed by Earl Grey’s government, the motivation for such amendments was to lower the cost of the poor relief system already in place and replace it with a more efficient system based around the creation of the workhouses. It was at this time that the destitute and unemployed would find themselves forced into this harsh system so well described by Charles Dickens in his social commentaries.

Unsurprisingly, it was met with much hostility and eventually the act needed to be further amended, particularly after the scandal of the Andover workhouse conditions.

With growing waves of opposition by the late 1830’s, Chartism as a movement began to take shape as the need for universal male suffrage was seen as necessary to instigate change.

Thousands of working men from across the country were united by the belief that the franchise and political reform could be a means to an end to bring about the reversal of so many social injustices of the day.

With the movement and its ideals gaining more traction, strongholds in the north of England as well as the Midlands and the Welsh Valleys were dominant, however sympathy for the cause also extended to the south where the London Working Men’s Association was founded in 1836 by William Lovett and Henry Hetherington.

Meanwhile, in Wales in the same year, the Carmarthen Working Men’s Association became an important platform for the regional Chartist growth.

The soon to become full-scale movement benefited greatly from the distribution of information through periodicals in order to reach wider audiences. Take for example, “The Poor Man’s Guardian” which was edited by Henry Hetherington and discussed issues of suffrage, property rights, the Reform Act and much more.

Other periodicals included the Northern Star and Leeds General Advertiser, with the Star having a circulation of around 50,000 reflecting the popularity of the movement and its sentiments.

The periodicals were vital in disseminating information, uniting people in a common cause as well as for the more practical reason of organising and advertising meetings, ensuring large attendance.

In 1837, William Lovett who had founded the London Working Men’s Association only a year earlier, joined six MPs and other working men to form a committee. This group would by the following year publish the People’s Charter, outlining six main sources of interest centred on the principle of giving working men the ability to influence, vote and contribute to law-making.

The changes requested by the demands set out by the People’s Charter in 1838 soon made the manifesto one of the most famous of its time. It also had the effect of unifying the disparate elements of the group so that a cohesive singular message reached everyone.

This was a movement united by tangible concerns such as political representation and economic improvement, as highlighted by the speaker Joseph Rayner Stephens when he described Chartism as “a knife and fork, a bread and cheese question”.

After launching the People’s Charter, the movement organised the National Convention to be held in London, emulating the structure of Parliament by referring to the delegates as MC (Member of Convention).

In the end, the Chartists were able to secure 1.3 million signatures to present to the House of Commons, however sadly their calls to be heard fell on deaf ears in the Commons as MPs voted not to hear the petitioners by a majority.

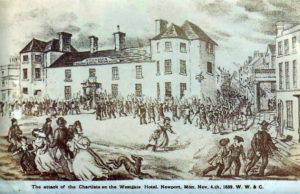

The more radical elements within the movement were now making calls for an uprising, leading to outbreaks of violence and many arrests. One such example occurred in Newport when around four thousand people marched into the town led by John Frost on 3rd November 1839. The result proved to be a disaster for the movement as the Westgate Hotel in Newport was occupied by soldiers who were armed, leading to a bloody battle with deaths and injuries and the Chartists forced to retreat.

Meanwhile, further attempts were made to launch risings in Bradford and Sheffield, however knowledge of their plans was leaked to the magistrates leading to it being stopped before it could ever really take off. Many of the organisers were thrown into prison for their involvement, with Samuel Holberry in Sheffield dying whilst serving his sentence.

Still undeterred, in May 1842 a second petition was launched and submitted to Parliament, this time with double the amount of signatures. The House of Commons once again rejected it, stifling the voices of around three million people.

That year would mark a significant battle for the Chartist movement and the defiance of working people in general, as massive economic hardship was inflicted through wage cuts and strikes were called in 14 counties of Scotland and England.

Inevitably, outbreaks of violence and disorderly behaviour followed, leading the government to call on the help of the military to suppress the anger of the people.

With mass striking and unrest sweeping the British Isles, the authorities were not keen to let the perpetrators go unpunished. The state response was harsh and equally defiant with massive numbers of arrests, particularly of leading figures such as O’Connor, Harney and Cooper.

The Chartists decided to pursue other avenues such as launching a National Land Company to buy shares and purchase land, however due to financial unviability it was forced to shut down.

In pursuit of more official routes to power, the Chartists put themselves forward as candidates in the general election and in 1847, Feargus O’Connor was elected for the Nottingham constituency, the first of his kind and a real boon for the movement.

Meanwhile, over on the continent, the 1848 revolution in France only served to increase the impulses of the Chartists as they organised protests in Manchester, Glasgow and Dublin.

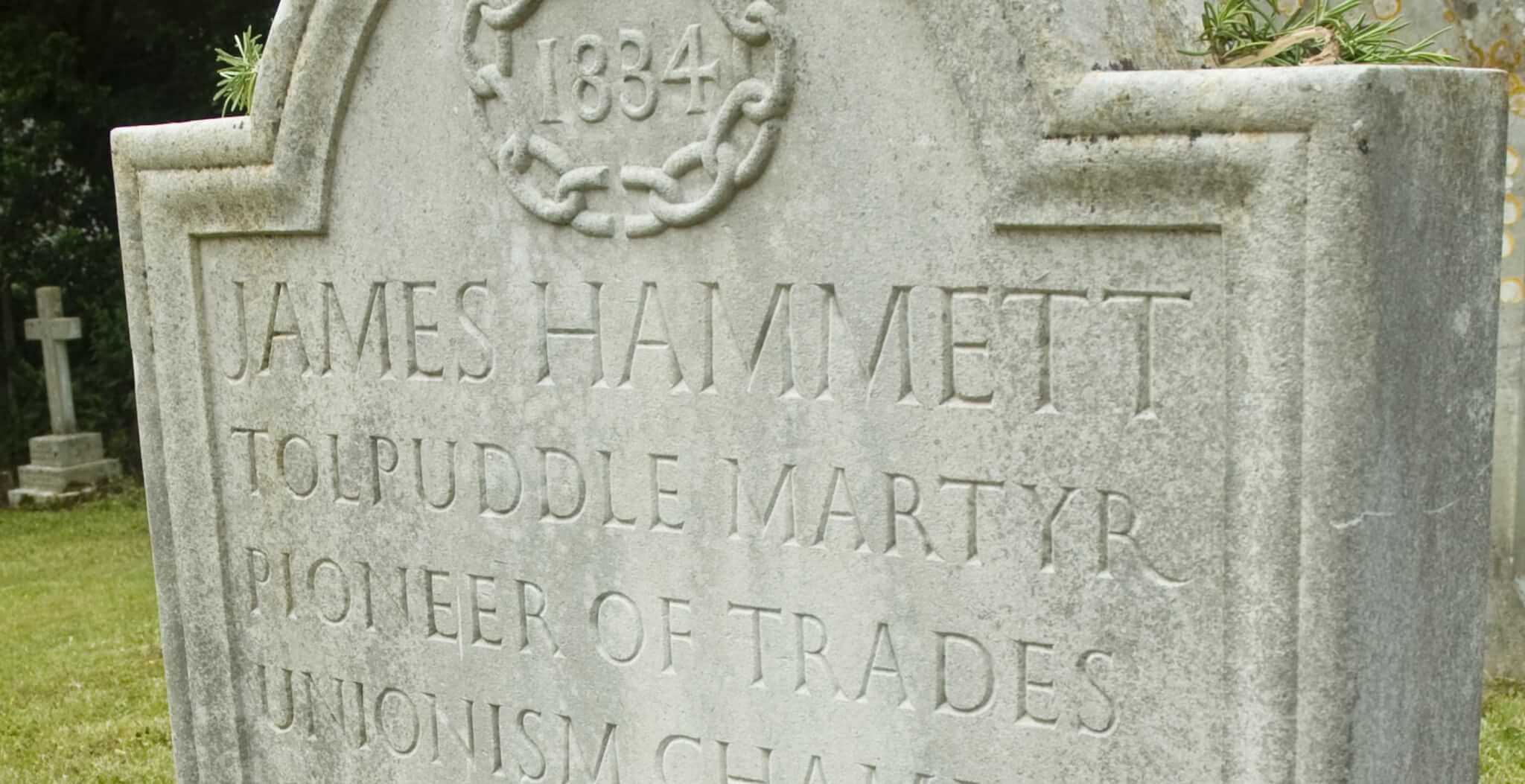

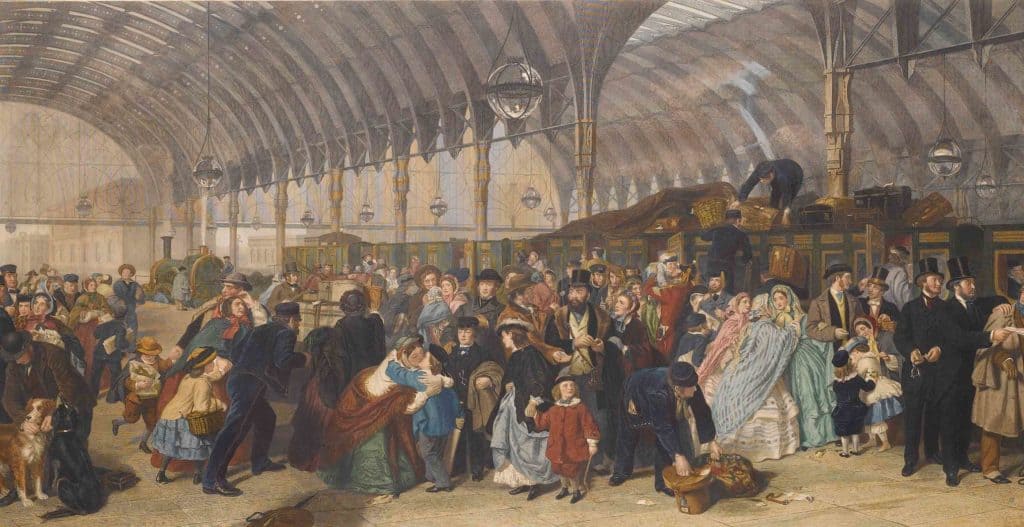

Upon hearing news of the preparations for mass demonstrations, it was arranged for 100,000 special constables to join the police force in order to make a show of strength. It was at this time that parliament used forceful measures to combat the movement once and for all. Measures which resulted in arrests, convictions and in the case of an individual called William Cuffay, transportation to Australia.

By the 1850’s, the peak of the Chartist movement had long since passed and all that was left were a few pockets of resistance.

The Chartist movement faded into history and whilst no tangible change had been achieved in terms of new legislation or reforms, their efforts were significant in paving the way for future reformers who would successfully campaign to extend the franchise and demand the political representation they deserved.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 18th September 2021.