“And the guns fell silent on Christmas Eve … ”

By December 1914, the war that was supposed to be over by Christmas was clearly far from it. The conflict on the Western Front was now characterised by two literally embedded armies facing one another across No-Man’s Land. The double line of trenches stretched, with account taken for natural features and other constraints, from the Swiss border to the North Sea. Trench warfare was the defining feature of the war that would later become known as the Great War, the war to end all wars, and then, with painful irony, the First World War.

Fighting had so far mainly consisted of heavy shelling by both sides interspersed with desperate forays by the infantry going “over the top” and, at the start of the war, cavalry engagements. The German, Austro-Hungarian and Russian forces had massive numbers of cavalry at their disposal, while the cavalry of the French and British forces was substantial, but not in the same numerical league. The logistics of maintaining cavalry horses created major issues for both sides. However, horses and other equids remained essential as pack and supply animals, for transporting artillery and as personal transport.

The Retreat from Mons: 16th Lancers on the march, September 1914.

The Retreat from Mons: 16th Lancers on the march, September 1914.

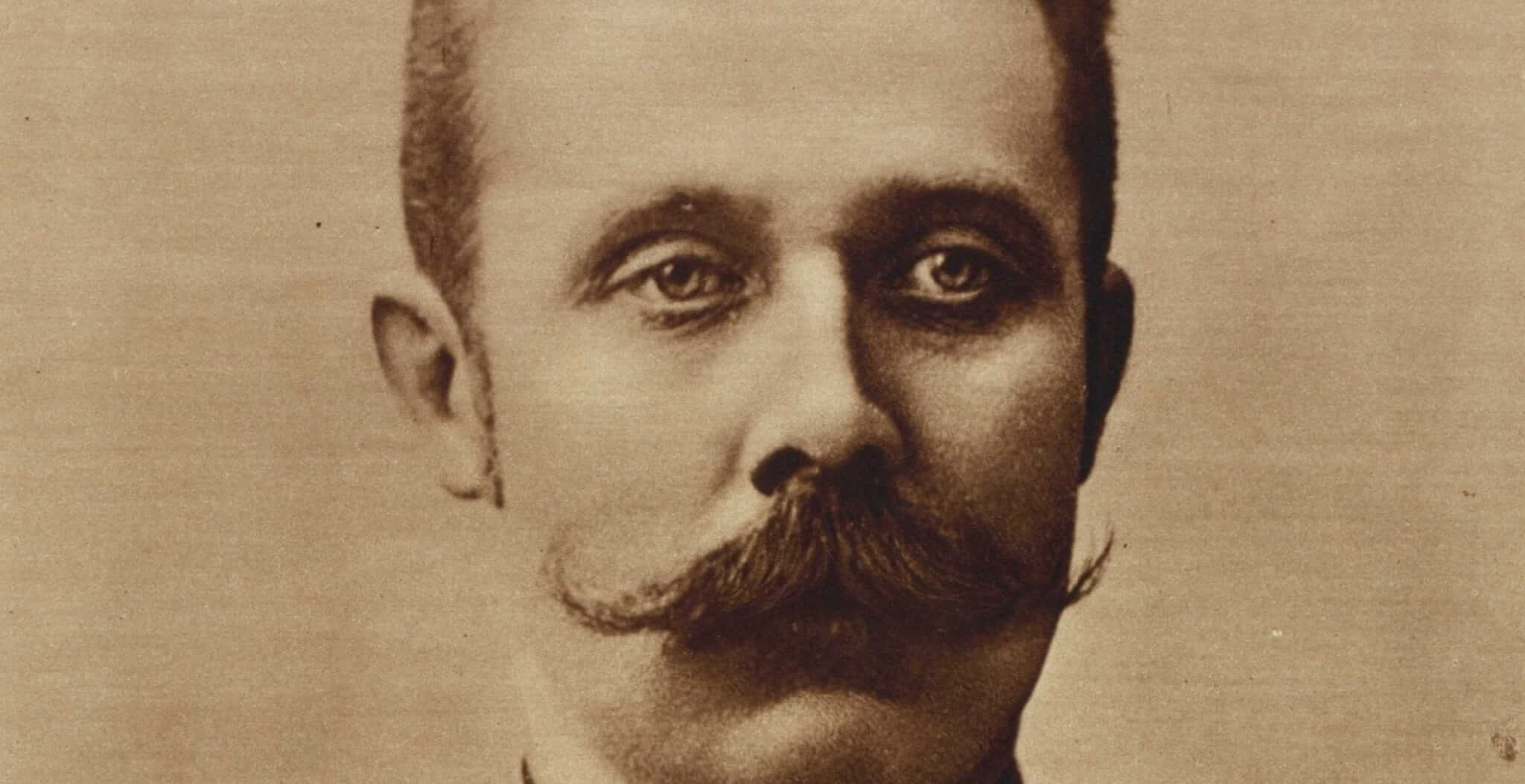

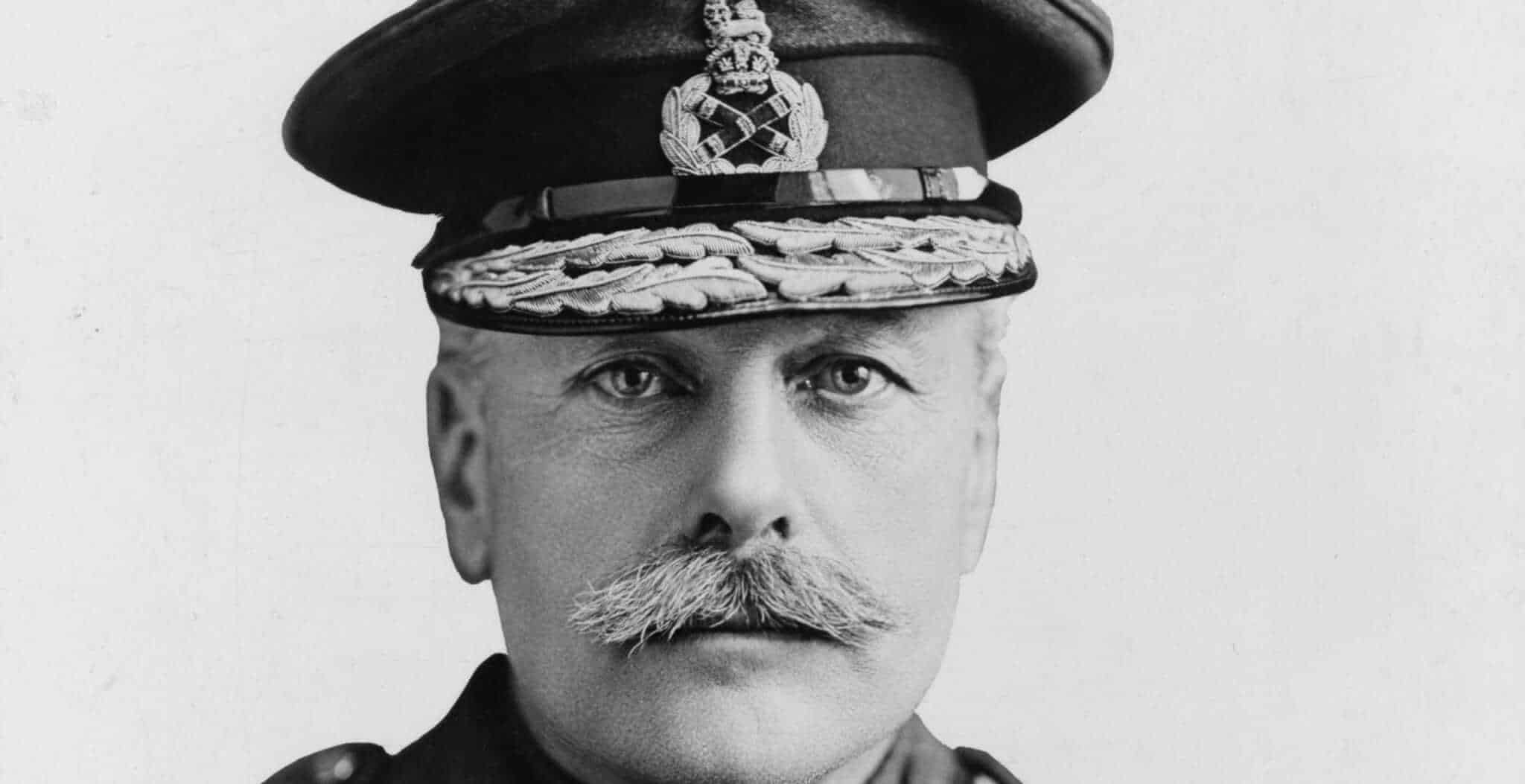

For the cavalry, the trenches had created a frustrating and futile theatre of war. Nonetheless, contemporary commanders such as Sir Douglas Haig and Sir John French continued to maintain their belief in the decisive part that cavalry played in military success. With a few notable exceptions, such as the Australian light horse charge at Beersheba later in the war, entrenched troops, automatic weapons and artillery behind the lines meant the traditional role of the cavalry was now redundant. The cavalry could no longer perform its traditional and age-old function of exploiting a break in the infantry lines. The arrival of tanks later in the war simply served to emphasise this.

On the frosty Christmas Eve of 1914, the distance between the two entrenched armies was often as low as forty yards (ca. 36 metres). They were so close that both sides could hear the men opposite singing traditional hymns and Christmas songs (and some less religious ones!), a poignant reminder of how far everyone was from home and how they yearned to return. As units from Saxony and Bavaria replaced some of the Prussian units across from the dugouts where the British Expeditionary Force was bedded in, reading letters from home and anticipating at least some comforts for the holidays, lanterns and candles began to light up the German trenches.

The dry frosty weather had come as an immense relief after the weeks and months of sodden, splashing life in the trenches and behind the lines. Despite the war, it was clear that both sides intended to celebrate their Christmas as best they could, and in the true spirit of the season. Both sides called out to one another and the British applauded the fine singing of their German counterparts. The German soldiers had been sent small Christmas trees, and these too were soon decorating their trenches.

The shouting and singing developed into a kind of friendly match between both sides, though not surprisingly it also included shouts of “Go home you English!” and the like. Then the German soldiers began to call out to the British soldiers to come across, letting them know that they had no intention of shooting: “If you don’t shoot, we don’t shoot”.

The British Expeditionary Force was located in the region of Ploegsteert, a Belgian town. Inevitably it was given the laconic name Plugstreet. Letters home suggest that the first to take up the offer to cross No-Man’s Land in friendship were soldiers of the Seaforth Highlanders at about 8.30 pm on Christmas Eve.

Taking rifles and ammunition with them, but not shooting, they began to cross the 300 yards or so that lay between them and the 10th and 20th Bavarian Regiments. Crossing that short distance must have seemed the ultimate in endurance. Once well across the ground littered with bodies and the detritus of shelling, they were greeted warmly by the German soldiers, who pressed cigars and cigarettes on them.

Slowly, but surely, it began to dawn that the entirely spontaneous truce was going to hold. Troops of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment recalled someone on the German side shouting out for rum, or a soldier offering it to them, and then crossing No-Man’s Land with the bottle to cheers and shouts. Soon both sides were swapping Christmas treats, smokes and drinks, along with newspapers and personal items like buttons and hats.

The impossible was happening. The frosty night, the singing, the warmth of the Christmas lights, and the rising moon “making even the hideous barbed wire entanglements shimmer with tiny lights, like a Peter Pan fairy glen” as one officer in the Highland Regiment described the scene, had worked a unique magic. The Christmas Truce of 1914 lasted four days, and would not be repeated again in the course of the war.

Numerous letters home recount the experiences of the British soldiers during the truce, and there was also, for the first time in war, a photographic record taken by the soldiers themselves thanks to the availability of the Kodak Vest Pocket Camera. This novel and inexpensive folding camera fitted into a small case that could, as the name suggests, fit into the vest pocket of a shirt or jacket. It was so popular among the troops that it became known as the Soldier’s Kodak.

The cameras may have been popular among the troops but they were viewed with suspicion by the top brass. Bad publicity at home and providing too much information to the enemy were seen as likely outcomes of soldiers with cameras kept handily in the pockets of their uniforms. As in previous conflicts, the army wanted to control the appearance of images in the media only through official sources. Just before Christmas, an official ban was put in place on personal cameras: “But the message had either not spread through the regiments or soldiers had considered the chance to record their Christmas on film too tempting to resist amid the extraordinary events of the truce,” writes Mike Hill in his book “Christmas Truce by the men who took part”.

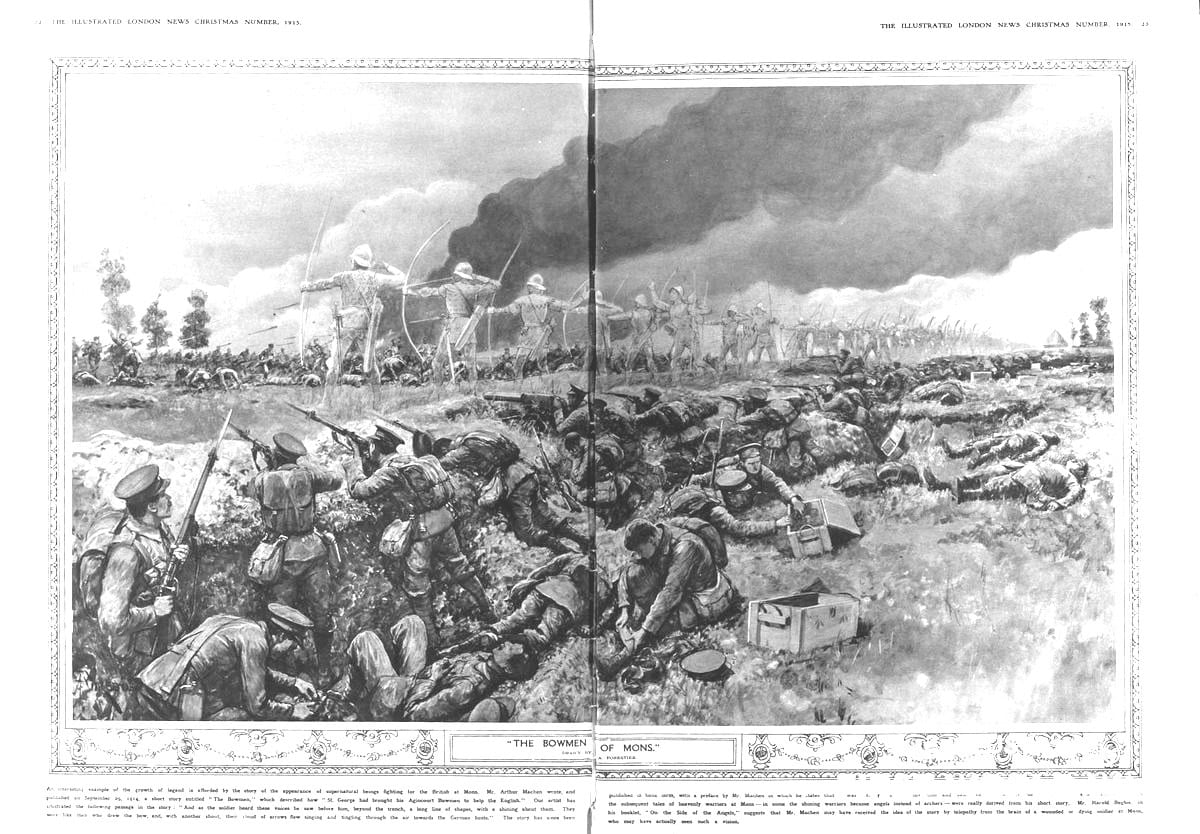

Despite the evidence of the letters and a relatively small number of photographs that reveal both private soldiers and officers from both sides took part in the truce, long afterwards many of those involved in the war recalled it almost as a fable. The Imperial War Museum holds many accounts of soldiers involved in the conflict, and Harold Lewis, engaged with the Royal Field Artillery and not present in France at the time of the truce concluded: “I think the whole thing borders on the fairytale and may be classed with the Russians with snow on their boots and the Angels of Mons”.

The Ghostly Bowmen of Mons fight the Germans from a drawing by A. Forestier, Illustrated London News

The Ghostly Bowmen of Mons fight the Germans from a drawing by A. Forestier, Illustrated London News

This view contradicting the evidence is not entirely surprising, giving the surreal atmosphere that hung over the entire first year of the conflict. The German plan had been to drive through Belgium and France as an unstoppable storm, swirling round towards the Swiss border. Instead, the Battle of the Marne on the Western Front had grounded the conflict in a tangle of barbed wire, a sea of mud and water-filled trenches, and the stench of putrefying bodies. As the stalemate continued into autumn, the strange reports of the battle at Mons had already brought a supernatural element into the war. The slaughter at Ypres had resulted in over 200,000 dead in total. Nor was the 1914 Truce universally kept along the line, and soldiers with no experience found it hard to believe even when recounted by those a short distance away.

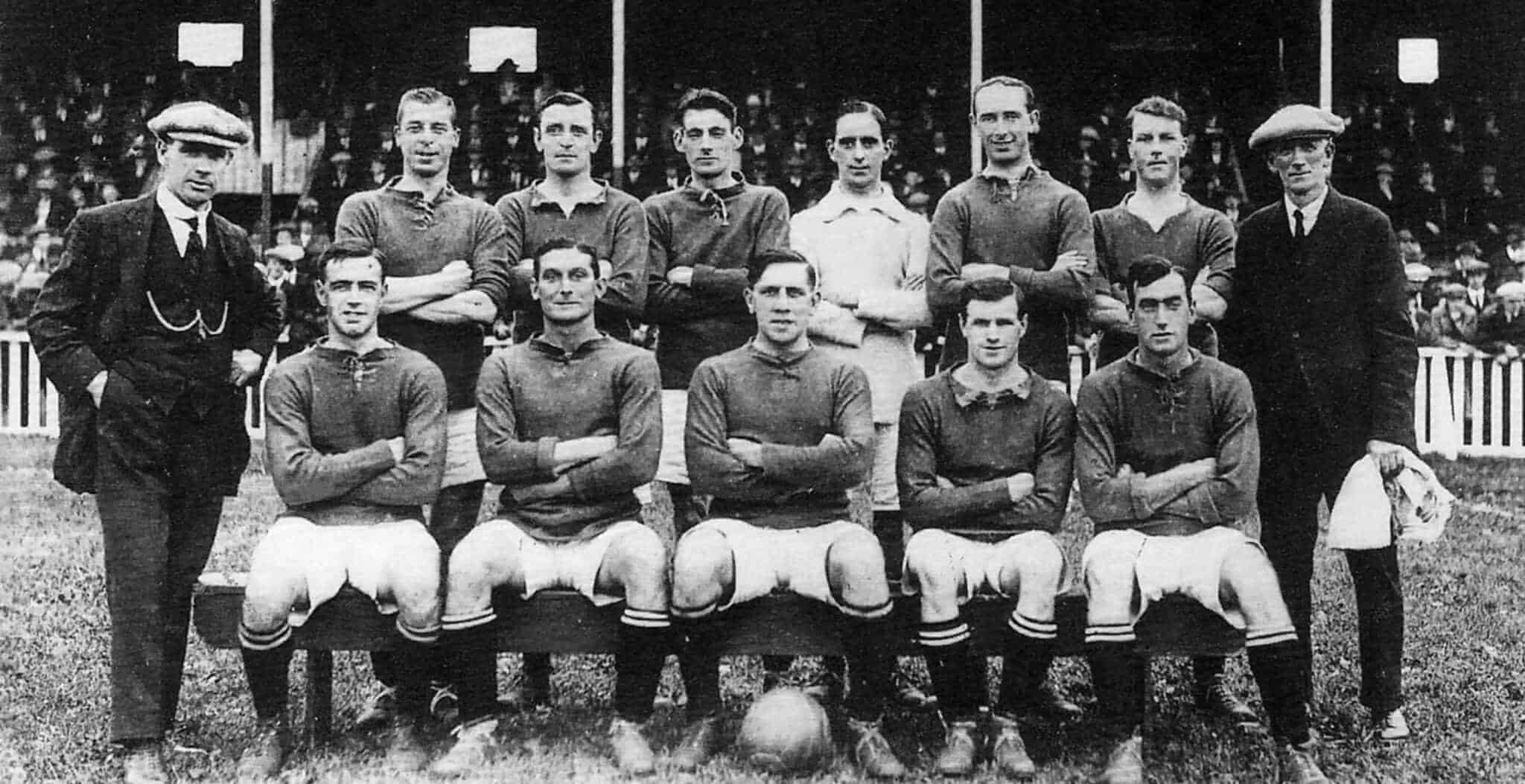

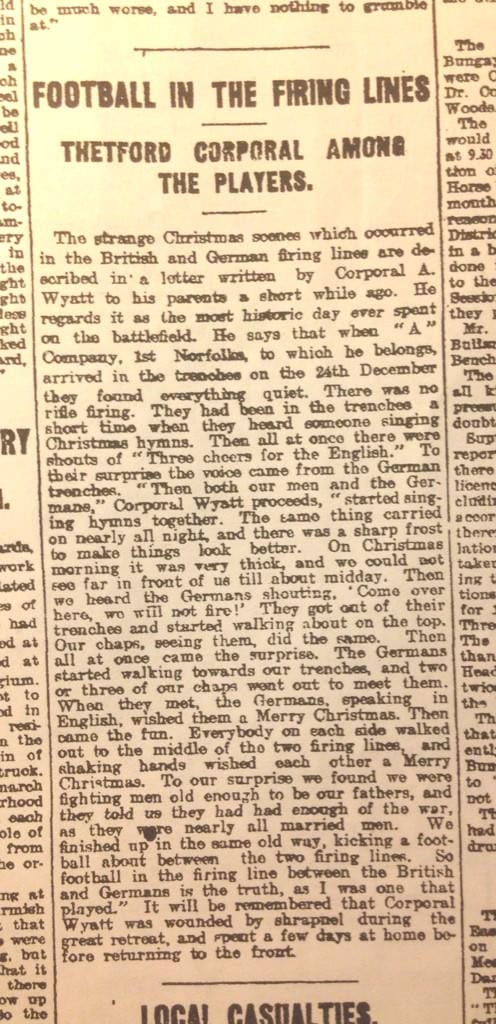

A legendary air also hangs over the famous football match that was supposed to have been played between both sides. From letters home it is clear that a football match or matches were definitely proposed for both Boxing Day and New Year’s Day. These didn’t come off, and the reasons given differ from letter to letter. Either the British authorities forbade it, or the German top brass, or the Germans went off the idea, or they couldn’t find a football; all these were given as reasons in different accounts. British platoons did play football on Christmas Day and it is clear that some of these were played in No-Man’s Land and were watched by German soldiers.

There’s also sufficient evidence to suggest that both sides had kick-abouts on Christmas Day. Drummer Arthur E. Salt of the 1st Battalion, North Staffordshire Regiment maintained that there was a football match on Christmas Day and that the result was England 2, Germany 1. Another account stated that one regiment held a football match with the Saxon regiments, and the result was 3-2 to the Saxons. However, several of the accounts were made to the media many years after the original events, and a short fictional story published by Robert Graves giving the same result – that is, 3 – 2 to the Germans – may have cemented the legend. A single account on the German side by Lieutenant Johannes Niemann, of the 133rd Saxons, does suggest a more formal match occurred, but it too is of later date.

Many of the British accounts relate how sorry the soldiers felt for their German counterparts, and how young and inexperienced some of the soldiers were, compared with the British regulars. The losses of Ypres had also brought about a change on the British side, with more reservists and new recruits joining the ranks. The pressing of gifts by both sides suggests mutual sympathy.

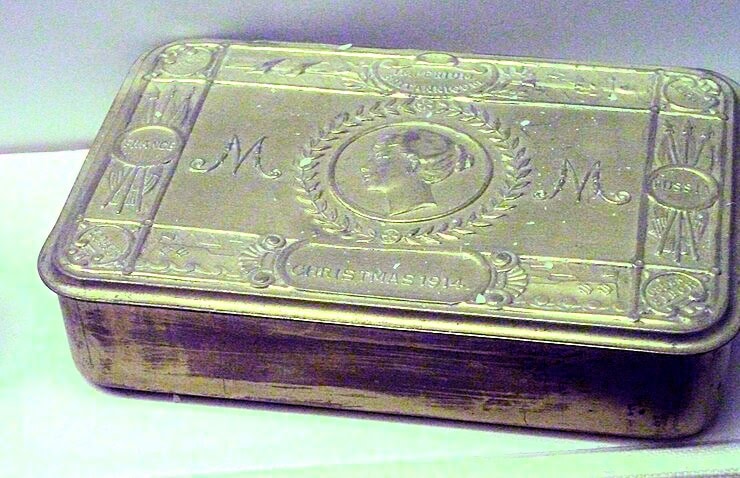

The British forces had received a special Christmas gift from the Royal Family, including a Christmas card, tobacco, pipe and cigarettes. Sweets and cigarettes proved to be popular exchanges.

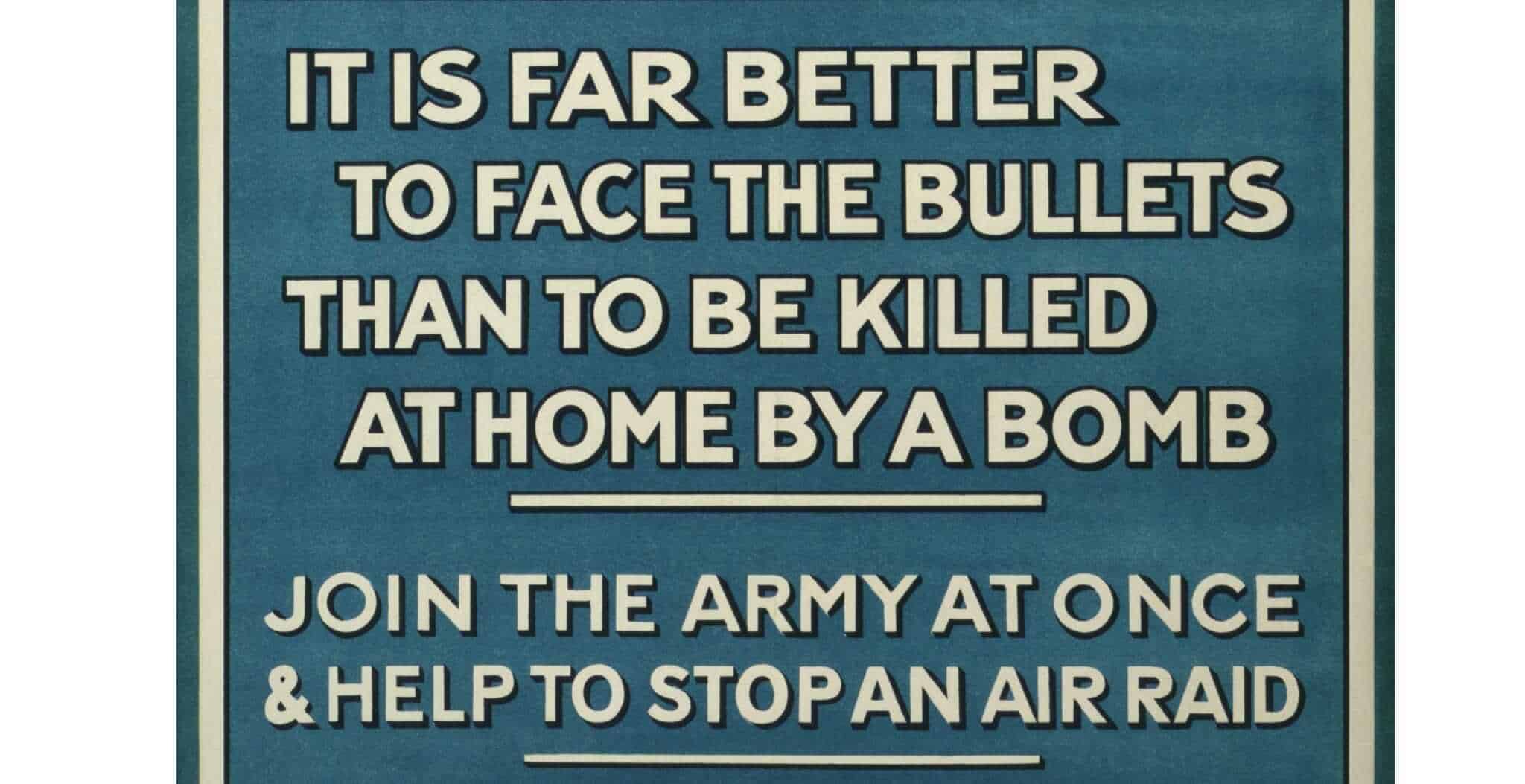

The comradeship shown across the lines is all the more poignant given that both sides had organised such intensive patriotic campaigns in the lead-up to the war. These campaigns had stressed an essential, almost primeval enmity between Britain and Germany. Many of the German soldiers believed that the British always shot prisoners and questioned their British counterparts about this again and again during the truce. The British soldiers were astonished to find themselves meeting and greeting young German men aged eighteen to twenty-five as well as “very old men”, and not the hideous monsters they had been led to expect. Some of the German soldiers they spoke to had worked in London, Glasgow, and elsewhere in Britain prior to the war. Young German soldiers of the Saxon regiments stressed their kinship to the British and their shared Christian faith. They sang “Stille Nacht” and called over to the British to sing the carol in English.

It was not simply a brief interlude when friendship was extended between those at war, but also a time when the full horrors of war were brought home to them. Both sides took the opportunity to bury the dead who had been lying in the No-Man’s land between the trenches, sometimes for weeks. Capt. John Robert Somers-Smith of the 5th City of London Battalion, London Rifle Brigade saw bodies blown to pieces for the first time, writing home: “I tell you it made me feel what an awful crime against humanity war is”. In his letter home, Lt Alfred Peveril Le Mesurier Sinkinson, 2nd Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers, wrote “when you are out here you begin to realise that sustained hatred is impossible”.

Against rising peace movements at home and the threat of revolution in Russia, these were not sentiments that the commanders on either side wanted to encourage. When some of the reports sent home were published in the press, the army chiefs on both sides clamped down hard, ordering there to be no more fraternisation. This, they uncompromisingly stated, was not a truce, but treason. Not everyone at the front was in favour of the truce, either. The historian Simon Jones also suggests that some of the officers may have taken the opportunity to carry out some reconnaissance during the ceasefire. The memory of a genuine truce remained though, and as time passed its significance increased rather than decreased.

As the historian Alistair Horne emphasised: “To a sociologist studying human behaviour during the First War one of the most astonishing revelations must be the extent to which fighting men of all nations adjusted themselves to, and then accepted over so long a duration the mutilations, the indignities, the repeated displays of incompetence by the leaders, and the plain bestiality of life in the trenches”. This knowledge highlights the uniqueness of the humanity, fellowship, and even humour displayed during the Christmas Truce of 1914.

Dr Miriam Bibby FSA Scot FRHistS is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published: 23rd December 2024.