A roadside plaque near Estcourt in KwaZulu-Natal commemorates the capture of Winston Churchill by the Boers on 15th November 1899 when an armoured train was ambushed.

General Redvers Buller described the incident as “inconceivable stupidity” when criticising the commander of the British garrison in Estcourt, Colonel Charles Long, whose men were supposed to be guarding a bridge over the Tugela River at Colenso.

Instead, Long took his troops back to the safety of Estcourt and then put them on the armoured train to patrol the railway line every day. It was unaccompanied by mounted troops and its mobility was limited by the rail tracks, so it was at the complete mercy of Boer field guns.

General Louis Botha, who was reconnoitering past Ladysmith with a small force of commandos, must have rubbed his eyes in disbelief when he saw the train steaming north towards Chieveley soon after 8 a.m. on November 15. It carried 150 men in three armoured trucks in front and behind the engine with a seven-pounder ship’s gun visible in a loophole.

Churchill was on the train at the invitation of his friend, Captain Aylmer Haldane. He had arrived in South Africa as the war correspondent for “The Morning Post” and in Estcourt he found that Haldane had been given command of a company of the Dublin Fusiliers after his own regiment, the Gordon Highlanders, had been trapped in Ladysmith by the besieging Boers.

Always ready for a dangerous adventure, Churchill boarded the train with Haldane and his men but they were cut off and attacked just beyond a bridge across the Blaauwkrantz River where the line sloped steeply upwards and the train was forced slow down. Boer gunners loosed off a couple of artillery shells and, as they expected, the engine driver put on steam and crashed headlong into rocks blocking the track. All three trucks were derailed, disgorging their human cargo, but the steam engine remained upright.

The Boers poured shells and bullets into the stranded steel whale and soon put the naval gun out of action. The upturned trucks gave little cover to the British, some of whom ran to freedom across the veld while others were hunted down and captured.

While Haldane and his men kept up a steady fire, Churchill directed the engine driver and an hour later they succeeded in getting the steam engine past the derailed trucks. When it stopped on the far side of the Blaauwkrantz River bridge, Churchill leapt off and went back to find Haldane and his Irishmen but was fired on by two Boer marksmen.

He ran into the safety of a cutting, saw a platelayer’s cabin in the distance and made a dash for it, only to be confronted by red-bearded “Rooi Piet” Oosthuizen, who aimed his rifle and yelled: “Surrender or I shoot!”.

Churchill felt for his 10-shot Mauser automatic pistol but he’d left it in the engine, so he had no option but to give himself up.

An elated Botha cabled Pretoria with news of the battle and his important prisoner. Four members of the commando were wounded and the British lost four dead, 14 wounded and 58 taken prisoner.

Churchill awaited his fate at the Boer camp, knowing that a civilian in a half-uniform who had taken an active and prominent part in a fight was liable to be executed. Eventually, a Boer field cornet arrived and told him: “Although you’re a newspaper correspondent we’re not going to let you go, old chap, because we don’t catch the son of a lord every day!”

Churchill and 50 other prisoners were locked up in Pretoria’s State Model School, from where Lord Randolph Churchill’s son argued his case with the Boer authorities. They contended that he had prejudiced the Boer operation by freeing the train engine, therefore he was a prisoner of war.

Immediately after hearing the verdict he resolved to escape. He studied the sentries’ movements and, on the night of December 12th, he saw an opportunity when a sentry patrolling the high garden wall walked over to his comrade and they chatted with their backs to him.

Churchill stood on a ledge, seized the top of the wall and quickly scrambled over the ornamental metalwork on top. He jumped into the adjoining garden and then calmly strolled through Pretoria, the burghers paying him no attention. He wore a civilian’s brown flannel suit, had £75 in his pocket and four slabs of chocolate – but no map or compass.

He walked south, struck the railway line and followed it for two hours to a station. He boarded the next goods train that arrived, climbed out before dawn and hid among some trees.

“I realised that no exercise of my own feeble wit and strength could save me from my enemies, and that without the assistance of that Higher Power which interferes in the eternal sequence of causes and effects more often than we admit, I could never succeed,” he wrote in his memoirs. “I prayed long and earnestly for help and guidance. My prayer, it seems to me, was swiftly and wonderfully answered.”

After nightfall he approached some houses around a coal mine. He knew that in the towns of Witbank and Middelburg there remained a few English residents who had been allowed to stay in the Transvaal to keep the mines working, and hoped he would be led to one of them. He knocked on the door of a house and was admitted by the English-speaking owner. He was John Howard, manager of the Transvaal Collieries, who had become a naturalised Transvaal burgher before the war.

“Thank God you have come here!” he exclaimed. “It is the only house for miles where you would not be handed over.”

Churchill was fed and hidden in the mine. At 2 a.m. on December 19, a week after escaping, his rescuer concealed him among a consignment of wool bales on a truck going to Lourenco Marques (now Maputo) in Portuguese Mozambique. When the train arrived he reported to the British Consul and was put aboard the weekly steamer leaving for Durban that night. He commented: “It might be said that it ran in connection with my train.”

He was given a hero’s welcome in Durban, made a speech on the steps of the town hall and returned to the war zone where he had photos taken with the derailed trucks.

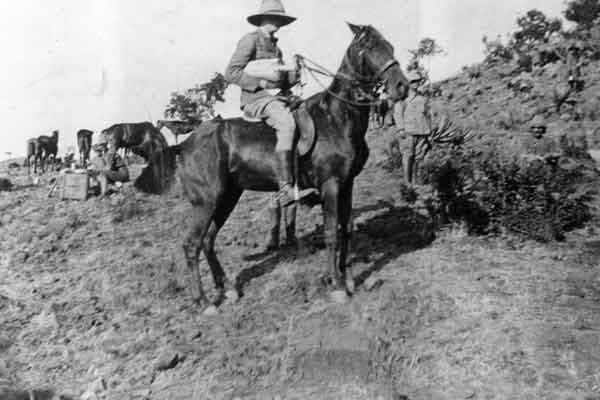

General Buller agreed to give him a commission in the South African Light Horse and he was with Buller when the British broke through to lift the siege of Ladysmith. When they reached Pretoria on 5th June 1900, Churchill cantered into town and located the Model State School. The sentries threw down their rifles, the gates were flung open and the released prisoners surrounded the Boers.

Riding on his popularity after returning to England at the end of the war, Churchill entered politics and won the Oldham seat for the Conservative Party in 1900 at the age of 26. Forty years later he became Prime Minister at the age of 66 and brilliantly inspired Britons to resist Hitler’s tyranny in the dark days of 1940 when Nazi Germany attempted to invade the British Isles.

When he was appointed Prime Minister of a coalition government on 10 May 1940, Churchill wrote: “I felt as if I were walking with destiny and that all my past life had been but a preparation for this hour.”

He died on 24 January 1965, his 90-year-old heart defeated by a lingering cerebral thrombosis. It was 70 years to the day that his father had died – the final coincidence in a life of many amazing coincidences.

English-born Richard Rhys Jones is a veteran South African journalist specializing in history. His novel “Make the Angels Weep – South Africa 1958” is available as an e-book from Amazon Kindle.

Published: 11th October 2021.