Back in the monetarist and power-dressed 1980s, many an office notice board had a plaintive message pinned to it by harassed staff. The message was usually photocopied (or Photostatted, a term that was still in use then) and had been re-copied and handed round so many times that the ink was faded and hard to read. The message was: “When you are up to your neck in alligators, it is hard to remember that the original intention was to drain the swamps”. (Neck wasn’t the only part of the anatomy referenced, either.)

In other words, an unintended consequence of draining swamps may be an increase in evicted and unsurprisingly angry alligators, resulting in a much bigger problem. The more you try to fulfil the original instruction, the more alligators you encounter. These were of course allegorical alligators, not real ones. The little photocopied page about the alligators, which was a precursor to online memes, was really about staff morale. Being constantly under pressure to perform, and existing in a permanent state of crisis management, employees could no longer remember what the original goal was. They were too busy dealing with the snapping jaws of ongoing issues with whatever project they were working on.

Some companies might try to alleviate the problem by offering incentives to staff to get more of those swamps drained faster, and get rid of the damn alligators. But supposing the staff discovered that by adding new alligators to the project (still allegorical alligators, that is) they could claim more bonuses or incentives? Every day more and more swamps are cleared, yet more alligators appear, because there’s a bounty on them and no alligators at all means no bounty money.

The technical term for this is “a perverse incentive scheme” and the daddy of them all has provided it with its alternative name: the Cobra Effect. It arises from an anecdotal, yet plausible story dating from the days of the British Raj.

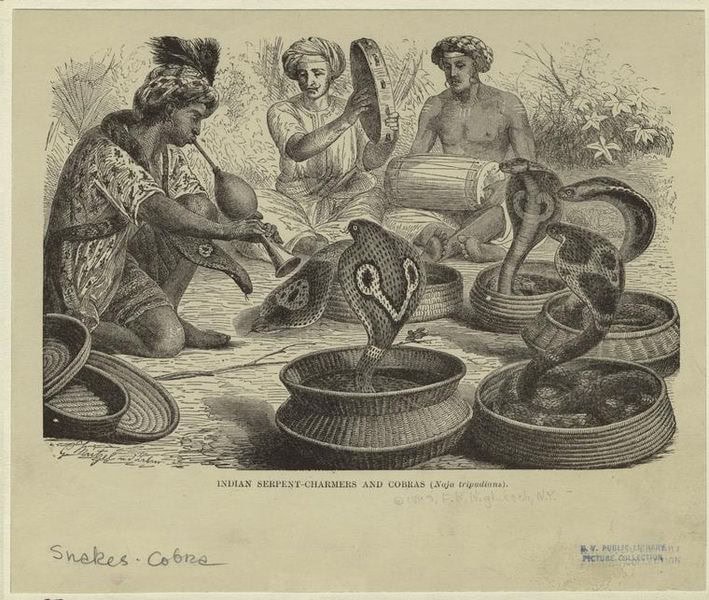

There’s no doubt that cobras and other venomous snakes were (and are) a source of danger in India and other places where they exist, even though they, like us and real alligators, are just trying to get by in a tough old world. However, at one point the cobra situation was so bad in the city of Delhi that the British authorities knew they must Do Something Stiff-Upper-Lipped and Totally British About It. A solution in the sporting spirit of fair play, too.

They put a bounty on dead cobras, paying anyone who could prove they had killed a cobra by bringing its dead body to the authorities. Seeing an opportunity, locals began to breed cobras, kill them, and produce their bodies for the bounty money. They kept on breeding cobras, and the authorities kept paying for the bodies. After all, it was a lot easier to raise and kill the cobras than go out and catch the wild ones lurking in cracks in house walls and shadowy corners. This way, there were always cobras and payments, and everyone was happy, apart from the dead cobras of course. The living ones had a job for life, breeding more cobras.

Eventually someone in authority twigged what was happening. “I say chaps, that’s just not cricket,” he said, removing the stack of dead cobras from his in-tray to his out-tray, crumpling up a handful of invoices, and aiming the paper ball in the general direction of the wastepaper basket (marked “Official WPB, strictly NO cobras to be placed in here”). He then took a sip of reviving Darjeeling, nibbled on a custard cream biscuit, and prepared a memorandum to Head Office.

Not being in the spirit of fair play as intended, the authorities cut off the cash, thus bringing to an end the perpetuum mobile of cobra production and payment claiming. The cobra breeders simply released all the remaining cobras they’d been raising, with the result that the cobra population rocketed and the situation in Delhi was worse than ever.

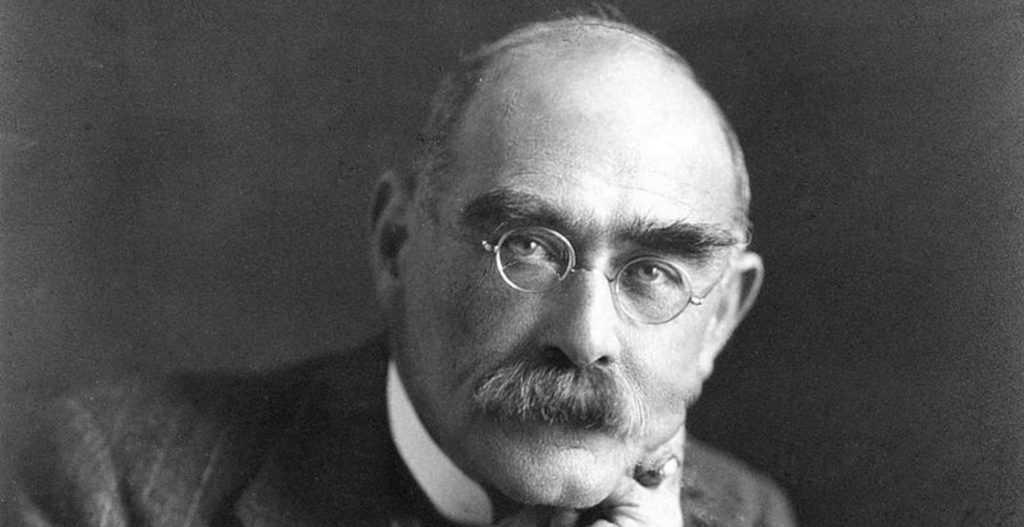

The term Cobra Effect is now applied in fields as varied as psychology and business to describe the undesirable and unintended consequences of providing an incentive. The first person to use this as an analogy that can be applied in other situations was an economist, Horst Siebert. For behaviourists, particularly those with an interest in positive reinforcement (giving rewards for desirable behaviour), this was an interesting lesson. It is possible to over-incentivise, and get exactly the opposite results of what you really want.

Anyone who knows anything about the work of Rudyard Kipling can see what the real problem was here. Not too many cobras, but a shortage of Rikki-Tikki-Tavis. The little mongoose of the Kipling tale made short work of snakes, venomous or otherwise. Perhaps the bounty should have been on the production and conservation of mongooses. Then in time there would have been a requirement for something further up the chain to control the mongooses, of course. “When you are up to your neck in mongooses…”

Dr Miriam Bibby FSA Scot FRHistS is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published: 14th June 2024