Looking back at photographs and films of the individuals who fought on the allied side in the Second World War is a curious experience. How young they were; how courageous in the face of death and injury; and how determined.

The story of the X-Craft is, in the words of James Gleeson and Tom Waldron in their classic book ‘The Frogmen: The Story of the Wartime Underwater Operators’, that of “brave men who worked alone under the water. Some wore fantastic-looking rubber suits with great webbed feet, some walked, or crawled, on the muddy bottoms of harbours in complete darkness, looking for mines, some bestrode torpedoes – the charioteers, they were called – some slipped through the black waters in midget submarines. They worked alone, in the dark, in enemy waters”.

It is one of the great ironies of war that along with death and destruction comes innovation. Military ingenuity must obtain results within a brief period in wartime. This was the case with the class of midget submarines constructed for the Royal Navy between 1943-44, known as the X Class.

Though little-acknowledged today in general histories, two of these submarines, known individually as X-Craft, played a key role in the D-Day Landings on 6 June 1944. There has never been a seaborne invasion like the D-Day landings, which led to the liberation of France from Nazi occupation, and eventually to the victory of the allies over Hitler and his forces in Europe.

The story of the X Class subs is certainly one of military resourcefulness. More than that, it is the story of how determination and commitment on the part of their crews led to remarkable military achievements. Even the largest submarine is claustrophobic. Considering the X-Craft were a maximum of 51 ft (16 m) long and around 5.5 ft (1.7 m) wide, the core three-man crew (along with essential divers, and other personnel) could not even stand upright.

They endured these conditions for up to two weeks at a time, taking turns to rest in the single bed, and allegedly often only surviving with the use of stimulants such as Benzedrine. They were on war rations too; mainly coffee, tea and beans allegedly, which leads to interesting speculation about subsea conditions. The crews must have been glad of periodic resurfacing for air! Passing over the stimulants and beans, Gleeson and Waldron paint quite a domestic image of the camping-style facilities including electrically heated double saucepan with which the crew “made coffee, heated tinned food, boiled potatoes and eggs, and washed up afterwards”.

The X Class submarines were designed primarily to get to locations such as harbours where enemy ships were stationed, and to destroy (the technical term was “neutralise”) them by laying charges. Small the submarines may have been, but they were crewed by some of the war’s elite forces, as appropriate for such sensitive missions: the commandos of the Combined Operations Pilotage and Reconnaissance Parties.

Many of the X-Craft submarines were built by Vickers Armstrong in Barrow-in-Furness. Powered by single shaft Gardner 4-cylinder diesel engines (converted from a type used in London buses!) and electric motors, the X-Craft were towed by the much larger T- or S-class submarines to their operation sites. Along the sides of each miniature sub were two whopping cargoes, consisting of two tons of amatol, a powerful explosive. These were dropped onto the seabed under the targets, and detonated by time fuses while the miniature subs quietly made their escape – if they could.

The divers were essential to the success of the operations, and played a critical role in laying explosives when the submarines first came into service. Once the X-Craft had located their targets, the divers would leave via the escape hatch in one of the sub’s four compartments and attach limpet mines to the bottom of the enemy vessel. They also cut through steel mesh nets that had been placed to guard the entrance to many harbours. In just a few brief years of war, diving gear had changed from heavyweight suits and helmets, with air supplied via a line, to rubber suits and air tanks. Along the way many trainees had volunteered to test out the new equipment in tanks of water, occasionally suffering from oxygen or nitrogen poisoning as they experimented with its use at varying depths.

The X-Craft operated from Port Bannatyne on the Isle of Bute, and took part in several missions before D-Day. They were high risk operations; several sank with all their crews, and other crews were captured or rescued by the larger submarines. Their best-known operation was that against the Kriegsmarine (the navy of Nazi Germany) battleship Tirpitz in Norway in 1943, which rendered the Tirpitz permanently inoperative. Two of the personnel involved, Lieutenant Cameron and Lieutenant Place, scuttled their craft and were captive on board the Tirpitz when the charges they had laid exploded. Both survived, to be later recognised as war heroes. The two scuttled X-Craft, X6 and X7, were salvaged by the Kriegsmarine and used to assist the development of their own miniature submarine, the Seehund.

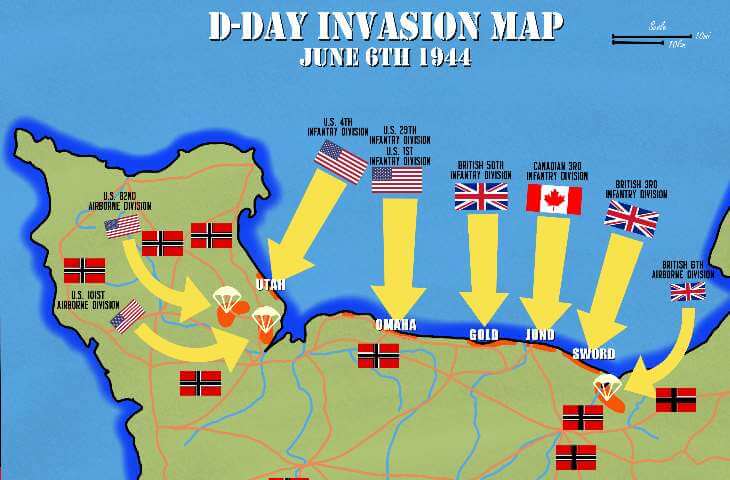

The celebrated D-Day landings of 6 June 1944 were part of Operation Overlord, the military strategy of the allied forces to invade France and liberate the country from the Nazis. The two X-Craft involved in the D-Day landings were X20 and X23. X-Craft also played an important part in the preparations for the advance, designated Operation Postal Able.

In January 1944, X20, under the command of Lt K. R. Hudspeth, reconnoitred the French coast for four days using periscope and soundings. The survey was supported by two divers who swam ashore each night to the beaches of the north French coast. This was essential work carried out under trying conditions, particularly increasingly bad weather that ultimately meant Hudspeth had to end the mission. Nonetheless, the mission was successful. Several Normandy beaches were identified and renamed for the allied invasion forces. These were Gold and Sword beaches (British); Utah and Omaha (American); and Juno (Canadian).

For the invasion strategy to work, the landing fleet had to be directed to the correct locations. This would be the task of X20 and X23, each crewed on this occasion by five personnel. The commander of X23 was Lieutenant G. R. Honour, and Lieutenant K. R. Hudspeth continued to command X20.

The period preceding the actual invasion was one of subterfuge. Misleading information was transmitted as to exactly what the allies were planning, including the creation of an imaginary rendezvousing of the major allied forces in Kent, along with fictitious American army units. Dummy paratroopers rained down into France one day before the actual landings. The operation was critically dependent on weather conditions and even the moon’s phases, since a full moon would mean the high tides that would assist the allies. Cloud and rain would render the Normandy Landings difficult if not impossible.

Originally planned for 5 June 1944, stormy weather conditions meant the Normandy Landings had to be delayed for a day. Conditions were still not ideal, and this had consequences for the X-Craft. They were already off the coast of Normandy, having set off on the night of 2-3 June, being towed part of the way. Delaying for even one more day increased the risk of being spotted by the German army, whose soldiers they could see clearly on the beaches through their periscopes.

The crews also needed to listen out for news of the invasion, which they could only do on the surface. This was relayed in coded form through BBC news bulletins, and by 1.00 on 4 June the crews knew that they were going to have to wait another day – or even longer. With limited power and oxygen, both X-Craft nonetheless had to take the risk of resurfacing during that period to ensure there was sufficient air. Additional oxygen bottles were available to the crews, enabling them to stay submerged for up to 64 hours, but if the landings were delayed for much longer, and that precious resource was used up, they would be unable to fulfil their task.

The secret messages conveyed in the news of 5 June must have come as a massive relief to the crews of X20 and X23. The landings started just after midnight on the morning of June 6th. The X-Craft went into operation at 4 am, as the landings were preceded by an intensive wave of bombing of the Nazi-held positions on the Normandy coast.

The X-Craft, as part of Operation Gambit, were to direct the invasion fleet to the correct beaches from a location some three miles offshore, and to ensure they avoided all hazards that would hinder the amphibious craft in landing. They had, in the words of Waldron and Gleeson, “the honour of being the first vessels to arrive in the assault area, and of being the forward guides of the seaborne invasion forces”.

They used landing lights, radio beacons and echo sounders to do this in support of the Canadian and British forces. Meanwhile, the American forces at Utah and Omaha beaches struggled in the face of strong winds that blew them off course. The X-Craft perhaps made a critical difference in ensuring efficient and effective landings at Juno, Gold, and Sword beaches, resulting in lower casualties. Once again, the divers, or frogmen, were essential to the success of the mission, clearing away the explosive devices and underwater hazards that cluttered the access for the amphibious craft. Two divers were killed and several more injured.

It is also worth noting that at least one Kriegsmarine one-man torpedo was found during the Normandy beach landings. Looking not unlike something from a Gerry Anderson puppet TV series, these weapons, ridden by “charioteers”, had originally been developed by the Italian navy. They were later adopted by all forces, and provided some of the inspiration for the creation of the X Class submarines. One month after the D-Day Landings, on 5-6 July 1944, the allied invasion fleet would be attacked by 24 manned torpedoes, resulting in the sinking of the minesweepers HMS Magic and HMS Cato. There were follow-up attacks later in July and August.

The X-Class submarines have been recognised in a handful of films. Only one survives, in the Royal Navy Submarine Museum, Gosport, although the eery skeletal ribs of two XT (training) craft can be viewed on the beach at Aberlady (East Lothian) in Scotland. Most were scrapped just after the Second World War, their cramped, claustrophobic, heroic conditions only living on in the memory of a few.

As Admiral Ramsey summarised in his report of the X-Craft on D-Day: “It is considered that great skill and endurance was shown by X20 and X23. Their reports of proceedings, which were a masterpiece of understatement, read like a deck log of a surface ship in peacetime, and not of a very small and vulnerable submarine carrying out a hazardous operation in time of war”.

On a more personal note, Waldron and Gleeson listed the names and hometowns of the frogmen who took part in the D-Day operations, from Newcastle to Purley: “So there you have them – bank clerks, engineers, carpenters, clerks, and students. Some of them had previously served in midget submarines and as human torpedoes. All of these bank clerks, engineers, carpenters, clerks, and students acquitted themselves nobly on ‘D’ day”.

Dr Miriam Bibby FSA Scot FRHistS is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published: 21st April 2024