Down through the ages the English Channel has saved Britain from invasion by enemy forces, as the great Spanish Armada found out to their cost in 1588. It looked so easy on the map, after all the Channel is but a few miles wide!

In the early days of World War II, this same watery barrier had deterred Hitler’s Nazi troops, isolating Britain and the British as the German army went on to conquer most of Western Europe.

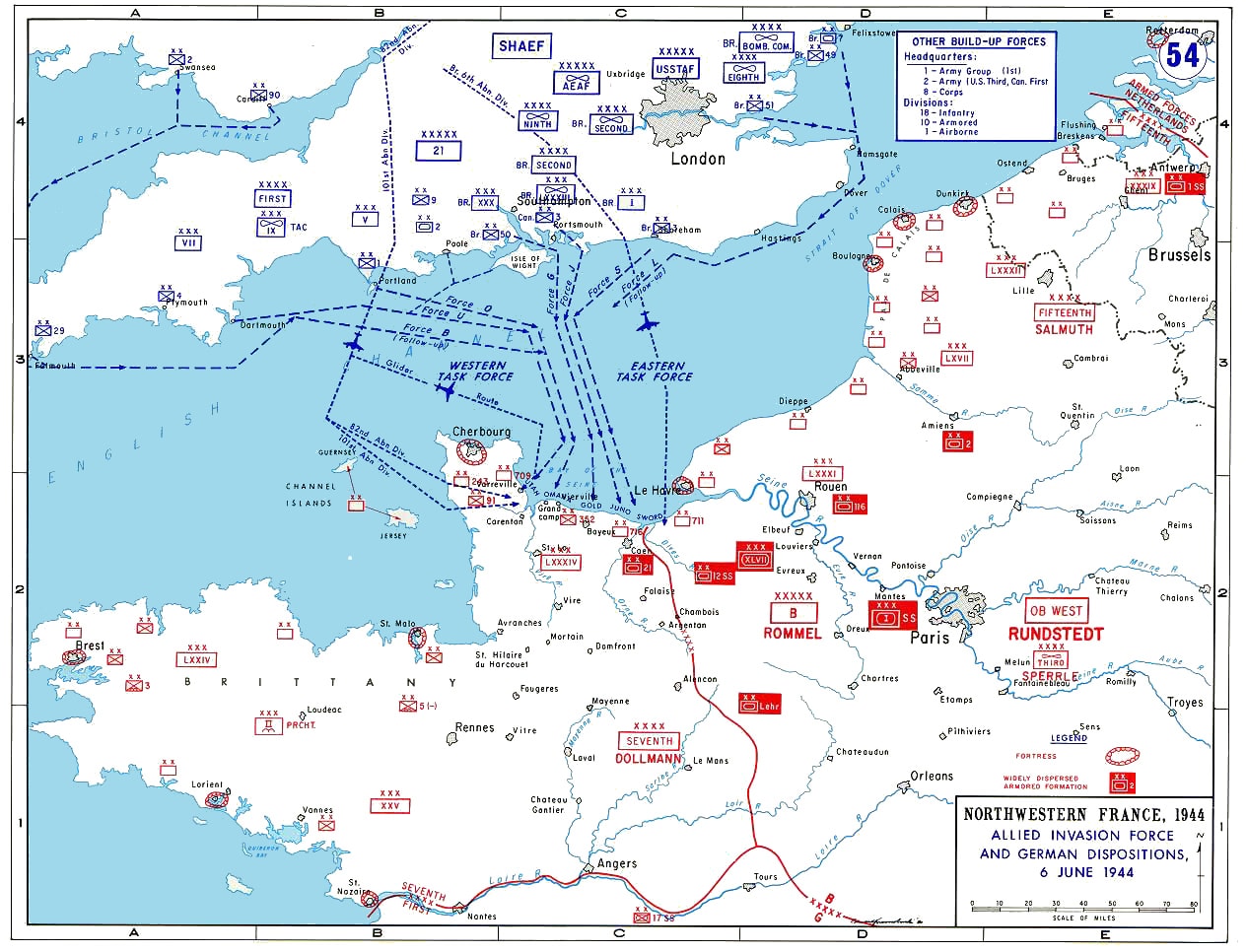

By 1944 the fortunes of war had turned somewhat: following successes in North Africa and southern Europe, it was now the Allied troops who were planning a return to northwest Europe across this narrow stretch of water.

The challenge presented to the Allies however was significant as the Germans had used their years in France to turn all of the Channel ports into fortresses, so much so that there was no question of capturing them in an attack either from sea or air.

And yet the Allies needed harbours in order to land the hundreds of thousands of men and millions of tons of supplies that they would need if Operation Overlord, the code-name given to D-Day, was to succeed.

And so the seemingly ridiculous idea was mooted of using artificial harbours to land and support what was to be the world’s greatest invasion. Such was the scale of the operation that two harbours would be required, each the size of Dover itself.

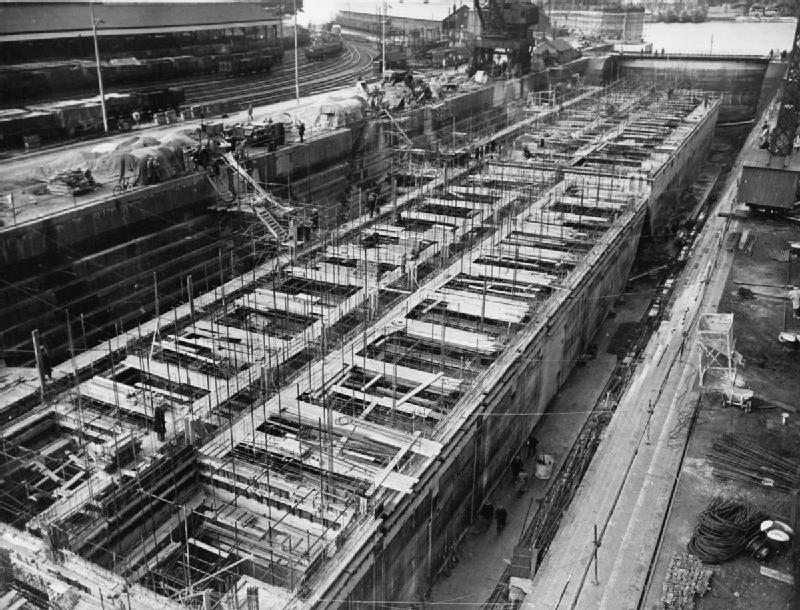

The harbours, code-named ‘Mulberries’, would consist of 73 individual prefabricated concrete blocks which when assembled would make up the ports, breakwaters and pontoons where ships could tie-up and unload their precious cargoes. Floating ramps would be used as roadways to allow the lorries to be driven directly on to the beaches.

The component sections of the harbours would be built in ports throughout the UK and towed across the Channel for final assembly off the Normandy coast.

The most spectacular feature of the Mulberry project was the construction of the huge, hollow blocks of concrete or caissons. Before being flooded, they each weighed in at between 1,500 and 6,000 tonnes. The largest ones measured sixty by seventeen metres, and were the height of a five-storey building.

A total of 40,000 workers were employed on this gigantic construction project which required the opening of special building sites at ports throughout the UK.

In the early hours of D-Day June 6th 1944, an invasion fleet of more than 1000 ships carrying 156,000 men headed towards the coast of Normandy, and the individual sections of the two Mulberry Harbours went with them.

Tugs towed the caissons and sections of concrete and steel pontoons which would make up the 7 miles of piers and jetties. After assembly one harbour would support the American sector opposite Omaha, the other the British and Canadian beaches, opposite Arromanches.

In the first six days of the invasion the Allies managed to land a third of a million men on French soil. However one of the most crucial logistical problems posed by sending a modern, fuel-guzzling army across the Channel was the supply of petrol.

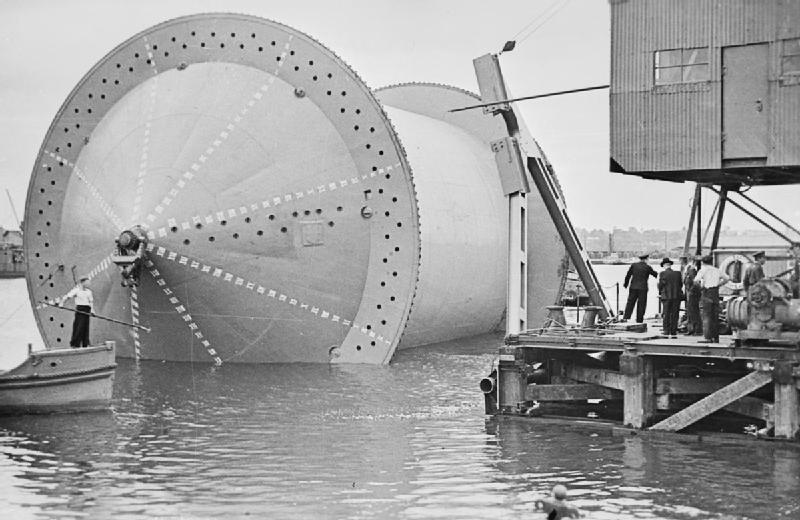

Yet again those crazy planners had come up with an equally crazy idea! An undersea pipeline would carry fuel from the Isle of Wight to Cherbourg.

The operation was codenamed PLUTO – nothing to do with the Disney cartoon character, but simply the initials for Pipe Line Under The Ocean. The undersea pipeline went into service in Cherbourg at the start of August 1944.

Eleven pipelines were laid across the Channel, and by April 1945 a total of 3100 tons of fuel was being delivered daily to keep pace with the Allied armies’ advance inland.

Published: 22nd November 2014.