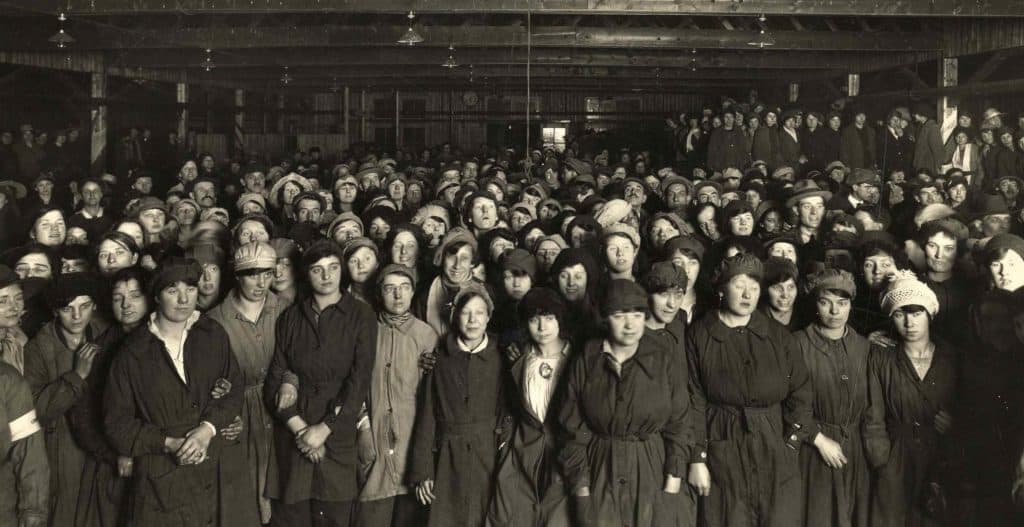

The Women Munition Workers Who Prepared The Devil’s Porridge.

They came to HM Factory Gretna from Ireland and every part of Britain and her empire, young working class women whose efforts would change the course of World War I. The site was the location of Britain’s largest cordite factory, a sprawling assortment of hastily erected wooden accommodation huts and brick-built manufacturing and storage sheds, all serviced by 125 miles of military narrow gauge railway line.

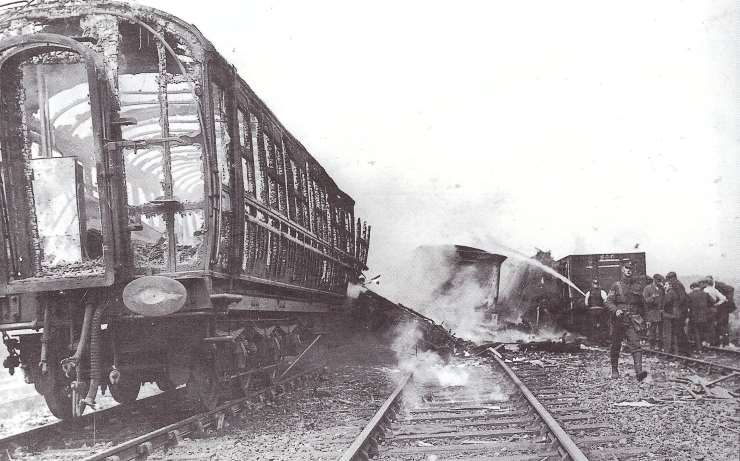

Prior to the war, the name Gretna had been better known as a fabled place of romance where runaway lovers could wed legally in the face of opposition from friends or family. Then, in May 1915, the area had created headlines when the Quintinshill signal box close to Gretna became the scene of the worst rail crash in British history.

The multi-train collision resulted in an official death toll of 227 people, though it is likely to be an underestimate. The dead included 215 soldiers from the Leith Battalion of the Royal Scots who had been on their way to Gallipoli.

Strictly speaking, Gretna Green is half a village in Dumfriesshire, the other half being Springfield. In 1915, the town of Gretna did not exist. Nor did the village of Eastriggs. In autumn 1915, all that changed was Mars moved in next door to Venus in response to the demands of the British generals of the western front for more shells to hasten the end of the war. It was an event that would have lasting consequences, not just militarily, but in terms of social and economic change.

The great shell crisis of 1915 was ostensibly a reaction to the disastrous events at Neuve Chapelle, which had seen the near destruction of Britain’s professional army under the inept group of generals who were later stigmatised as “The Donkeys”. It was arguably as much a crisis created by the military correspondent of The Times, Colonel Repington, at the instigation of Commander-in-Chief General Sir John French.

Repington’s despatches on “the need for shells” were published after he had toured the Western Front, including spending considerable time in discussion with General Sir John French, with whom he was already acquainted. The failed commander-in-chief blamed the disastrous Neuve Chapelle and following offensives on a shortage of shells, despite his despatch prior to the attack referring to adequate supplies.

In May 1915, The Daily Mail represented the situation as “The Shells Scandal: Lord Kitchener’s Tragic Blunder”. A few days earlier, Lloyd George had been appointed Minister of Munitions in Asquith‘s coalition government. By late autumn, work had begun on the nine mile long munitions factory that would eventually straddle the border from Dornock by the Solway in Dumfriesshire to Longtown in Cumberland.

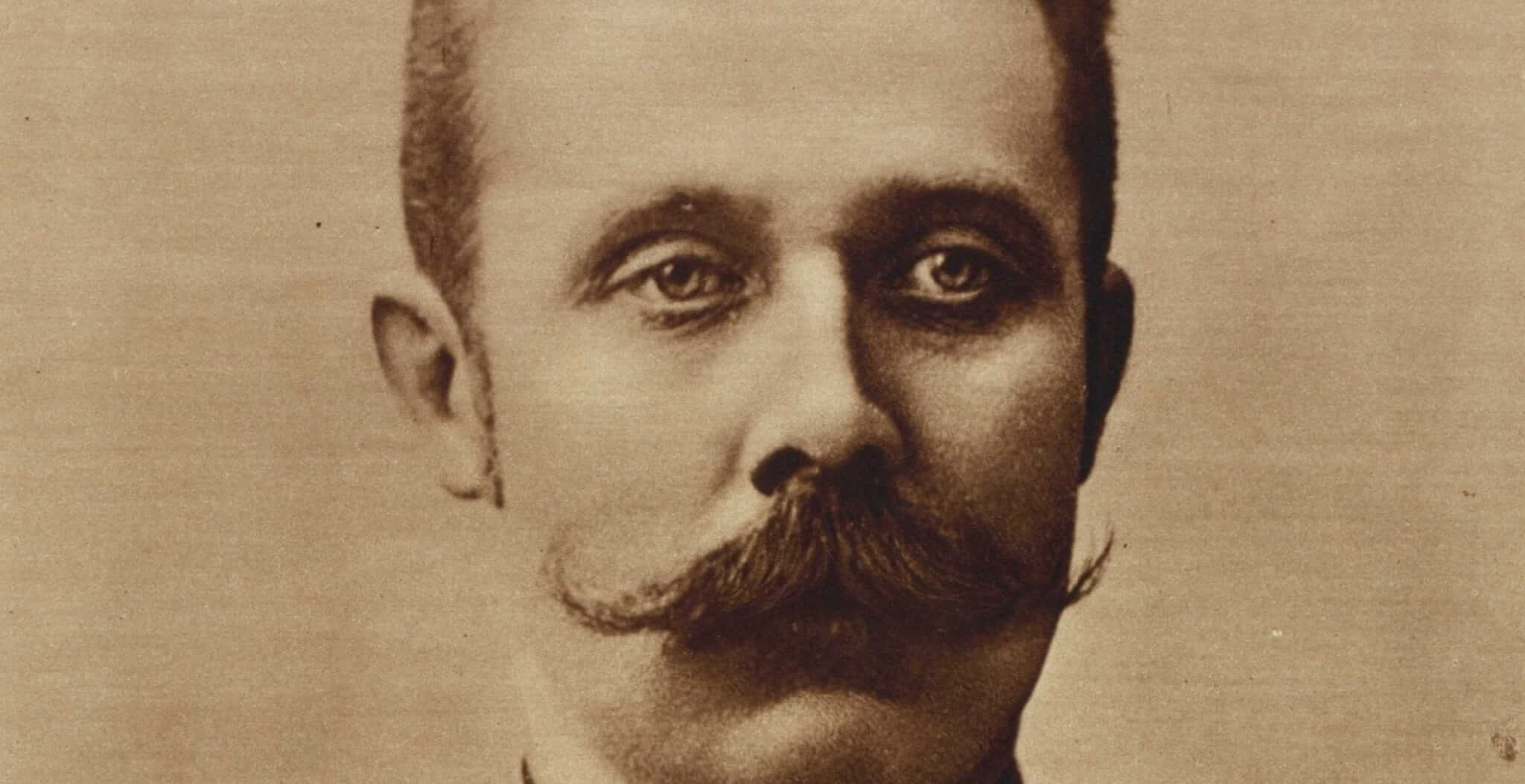

Estimates for the number of navvies involved in the construction work vary, but there were at least 10,000 and many of them were Irish. HM Factory Gretna was constructed in nine months, an astonishing achievement which was noted in a newspaper article by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. The author of Sherlock Holmes is also credited with the creation of the term “Devil’s Porridge” for the mixture of gun cotton and nitro-glycerine that was used to produce cordite as a shell propellant.

The first stage of the work involved charring cotton waste with nitric and sulphuric acid in pans made of stoneware to create nitro-cotton, or gun cotton. It was an extremely hazardous procedure, creating toxic fumes and the ever attendant danger of acid burns from splashes. The cotton was then washed in boiling water, followed by immersion in cold water and finally chalk rubbing, to neutralise the acid.

To produce cordite, gun cotton had to be mixed with highly unstable nitro-glycerine, which was created using glycerine from the soap industry, plus nitric and disulphuric acids. Nitro-glycerine production was so dangerous that no machinery could be involved. The materials had to be gently mixed in lead containers, allowing the nitro-glycerine to float up and be skimmed off. The nitro-glycerine was moved around site along lead channels under the influence of gravity alone!

Cordite was mixed by hand in broad vats. Conan Doyle wrote of the “smiling khaki-clad girls… swirling the stuff round in their hands” despite knowing that the risk of explosion was always present. The 34 engines that transported the material round the site from production to storage areas ran on compressed air, not coal, for that very reason.

Housed at first in the wooden huts that quickly became known as “Timber Town”, women were the principal workers on the dangerous, demanding process of producing cordite. Dressed in a uniform of trousers, crossover tunic and belt, with their hair often cut short but always completely covered in mob-style caps for safety reasons, the women collected the gun cotton from large heaps before tipping it into the vats and kneading it by hand. Their skin often turned yellow from handling the dangerous materials.

The hours were long too, as the clamour for devil’s porridge to feed the hungry guns at the front continued. By 1917, the factory was producing 800 tons per week and King George V and Queen Mary came to view and praise Gretna’s war effort.

Inevitably, there were serious incidents resulting in deaths, although it is hard to estimate numbers due to the secrecy that surrounds munitions production in times of war. Stories of fatalities did reach local papers, however.

In theory, the young women were independent working class women with money to spend. Gretna offered its 20,000 workers purpose-built schools, shops, a hospital and cinema. In practice, the workers were kept under surveillance and Timber Town was enclosed by barbed wire.

The Gretna administrators did their best to control leisure time access to the alluring pubs in Carlisle, including restricting local train services. However, some workers took the dangerous and out-of-bounds route on foot across the railway bridge to make sure they had some fun in the little free time they had.

Accusations of drunkenness among munitions workers had been made even before the construction of Gretna. Historian A.J.P. Taylor argued that Sir John French had blamed drunken munitions workers for the shortage of shells to cover up his own inadequacies. Local tensions and suspicions around those who had come to work at Gretna also increased with Dublin’s Easter Rising in 1916.

Whether the reputation for drunkenness was fair or not, it remained a popular subject for the press, with one cartoon showing two women munitions workers drunk on all fours in front of Carlisle’s Town Hall. The government’s response was to institute the Carlisle Experiment, also known as the State Management Scheme – the nationalisation of public houses in and around Carlisle and Gretna and the Scottish side of the Solway, plus those along the north Cumbrian coast as far as Silloth and eventually down to Maryport.

In all, the State took control over five local breweries as well as nearly 400 premises, including public houses and off-licences. This significant social experiment was not unique but it did become the best known example, lasting until the 1970s, when Edward Heath’s government brought it to an end. Under state management, opening hours were reduced, beer was weaker, advertising was limited and the time-honoured intimate snugs, parlours and smoking rooms were opened up into larger spaces.

The emphasis was as much on food and entertainment, particularly traditional pub games, as on drinking. In short, public houses became more family-friendly, a fact that was not popular in Scotland as it was seen as the imposition of English ideas. The mere fact that women were earning money and going into public houses to buy their own drinks was shocking to some on both sides of the border.

When the war ended, much of HM Factory Gretna was dismantled. However, housing built for married couples remains, along with a fine architectural legacy in the form of magnificent churches, including the former St Ninian’s RC Church, now the Anvil Hall. The River Esk pumping station north of Longtown is another local landmark and the heritage of the entire site is recreated in the new Devil’s Porridge Museum.

More importantly, the contribution of the young women would go on to influence every sphere of life, setting standards in what women could do, how much they could earn and what they could wear. As A.J.P. Taylor put it, “By the end of the war, it was no longer true that woman’s place was in the home.”