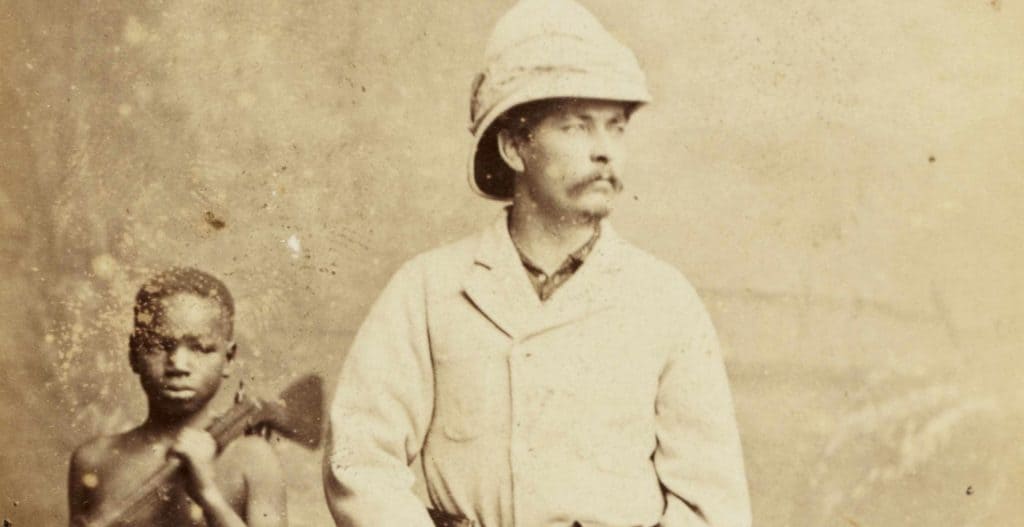

Dr. David Livingstone is a legend among explorers and adventurers, a true example of North Sea strength and Scottish grit. During his incredible life, Livingstone undertook three major expeditions into the Dark Heart of Africa, travelling a phenomenal 29,000 miles, a greater distance than the circumference of the earth. Achieving this in any circumstances is incredibly impressive, but doing so in the 19th century, during the Victorian era when almost nothing was known about the interior of Africa, is astonishing. It is no exaggeration to say that even the very first astronauts to walk on the moon in the 1960s knew more about its surface than Victorian explorers did about the center of Africa: it really was uncharted territory.

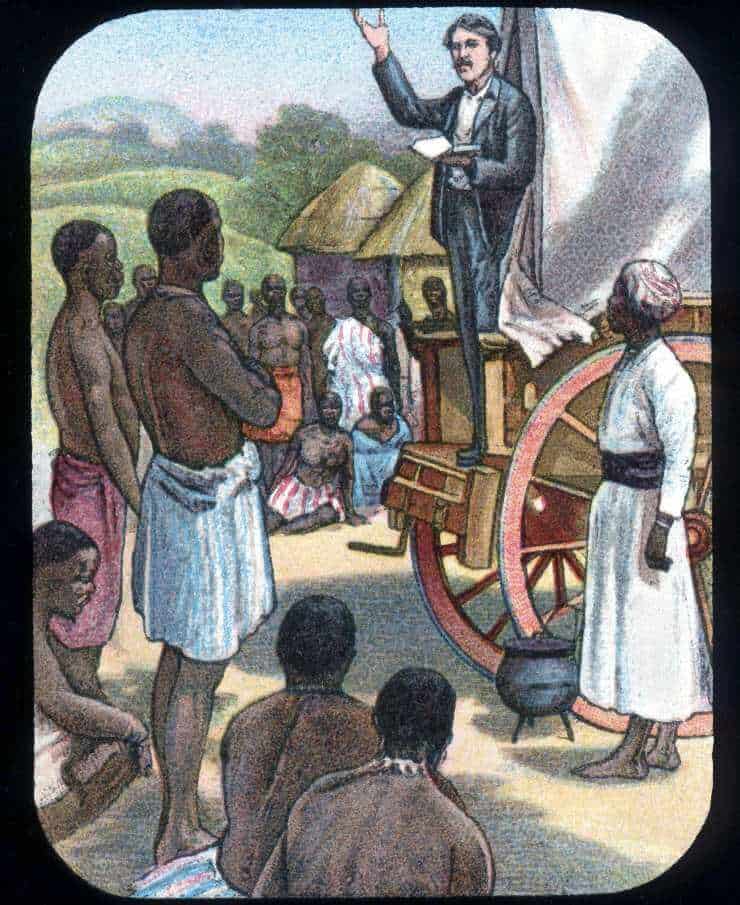

Livingstone was born on 19th March 1813 in Blantyre, near Glasgow, into a poor family. He was the second of seven children, and the entire family shared one room in a tenement building. At just 10 years old Livingstone went to work in a cotton mill as a ‘piecer’. He would tie the broken cotton threads together whilst lying under the machinery. Even at such a young age Livingstone was incredibly ambitious. Working at one of the more progressive mills of the time, meant that Livingstone had access to two hours of schooling after his 12 hour working days. Livingstone attended religiously, and was even known to stick his teachings to the mill machinery so that he could learn as he worked. His hard work paid off and having taught himself the requisite Latin to study medicine, in 1836 he enrolled at what is now Strathclyde University in Glasgow. Medicine was not his only focus however; he also studied theology and as a staunch Christian, went to Africa as a missionary to spread Christianity’s influence, if he could, in this unknown land. He had originally planned on going to spread the word in the Orient, but the First Opium War of 1838 put a stop to that particular notion. So instead he looked to the equally exotic and unknown Africa.

In March 1841 Livingstone arrived in Cape Town. He had another goal in mind while in Africa, other than simply converting the locals however. He also wanted to discover the source of the White Nile, and he devoted many expeditions across the African landscape to this end. The source of the smaller Blue Nile had already been discovered 100 years earlier by another Scot, James Bruce.

Unfortunately however, Livingstone was unable to achieve either goal. He only managed to convert one African, a tribal leader called Sechele. However Sechele found the Christian rule of monogamy too constricting, and soon lapsed. Livingstone never did find the source of the Nile, but he did find the source of the Congo instead, which in itself is no small achievement!

Whilst Livingstone may not have achieved his two goals, he achieved a huge amount nonetheless. In 1855 he discovered a glorious waterfall, which he christened ‘Victoria Falls’. In 1856 he became the first Westerner to traverse Africa from Luanda on the Atlantic Ocean to Quelimane on the Indian Ocean. He traversed the entirety of the Kalahari desert (twice!), proving that it did not continue into the Sahara as was previously thought. He did this latter journey with his wife and small children!

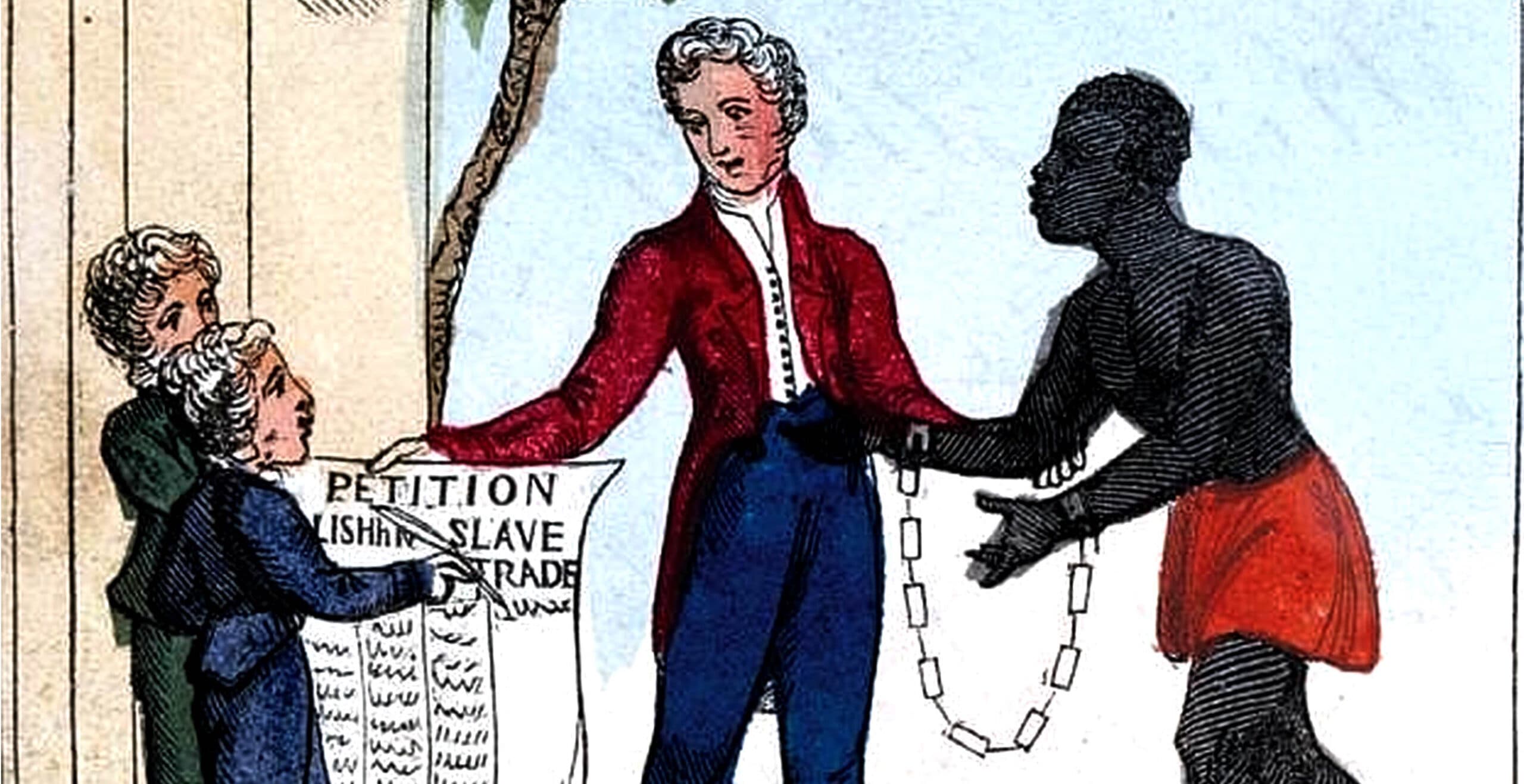

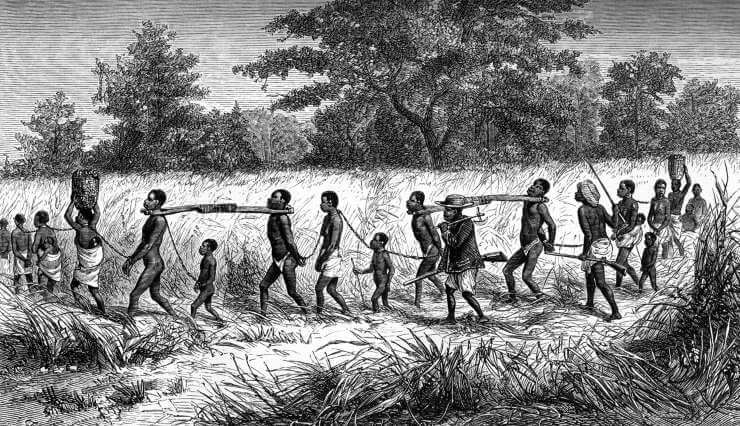

Perhaps his greatest achievement however, was his contribution to the abolition of African slavery. Great Britain and the United States of America had already outlawed slavery by this point, but it was still rife in the Arab continent and within Africa itself. Africans would be enslaved and traded in places in the Middle East. Africans would also be enslaved by other Africans from different tribes within Africa.

Although exact accounts differ, Livingstone witnessed a massacre of local Africans by slave traders on one of his earlier expeditions. Already firmly against slavery, this galvanized him further into action, and he wrote accounts which he sent back to the UK detailing the brutality of the slave trade. And a mere two months after his death the Sultan of Zanzibar outlawed slavery in his country, which effectively killed the Arab slave trade.

Livingstone’s accounts of what happened during the massacre so shocked and horrified British readers, that they indirectly allowed the beginning of colonisation in Africa by Western powers. It is events such as this that led to Livingstone being credited as being the ‘spear head’ of British imperialism, or even the precursor to the scramble for Africa. This is not indicative of the man himself however. He absolutely abhorred slavery, and furthermore he did not agree with big game hunting. He was also a great linguist and could communicate with the indigenous peoples in their own tongues. He had enormous love and respect for the African continent and its peoples. This may be why he is still loved in Africa, which is incredibly unusual for a white man from that century. Not only are there statues of Livingstone in towns in Africa, but the town of Livingstone in Zambia still bears his name today.

Livingstone’s final expedition was not only his last to Africa, but also his last expedition anywhere. He died on the continent on May 1st 1873. He was sixty years old when he died, which was impressive considering where he had travelled and everything that he had done. His expeditions would have been exhausting. He would have come up against all manner of horrific diseases, not to mention inhospitable terrain, extremes of temperature, potentially hostile natives and wildlife! All of this would have taken an inevitable toll on the explorer and missionary. He had actually managed to survive contracting malaria a colossal 30 times! He even patented a medicine for it called ‘Livingstone’s Rousers’. He also kept the disease at bay with a mixture of quinine and sherry. So maybe a gin and tonic to ward of mosquitoes and their nefarious infections is not such a bad idea after all!

Livingstone had actually been presumed dead already by this time. His letters had not been reaching home, his wife had passed away, he had lost or been robbed of all of his possessions and at the end was incredibly ill. There were some people who traveled into Africa to try and track Livingstone down, and discover whether he was indeed dead or alive. Luckily he was found alive near Lake Tanganyika in October 1871, by another explorer and journalist, Henry Stanley who upon finding Dr. Livingstone, allegedly uttered those famous words, ‘Dr. Livingstone I presume?’. Although in a poor state, Livingstone continued to search for the source of the Nile right up until his death two years later, although he was never to find it.

Dr. Livingstone was a linguist, a doctor, a missionary and an explorer. The man became the myth that became the legend who is renowned to this day for opening Africa up to the West, exposing some of its great mysteries and learning some of its great secrets. Although he died in Africa, his body was returned to Britain where it remains to this day, buried in Westminster Abbey.

By Ms. Terry Stewart, Freelance Writer.