As a keen amateur historian I’m fascinated with British history, however, I’ve always been drawn to the more unusual and lesser-known stories from our past. It was whilst thinking about what to write about I came across the Dreadnought Hoax of 1910. This incident not only left the Royal Navy of the day red-faced, but also offers a unique glimpse into the rigid social structures of Edwardian England.

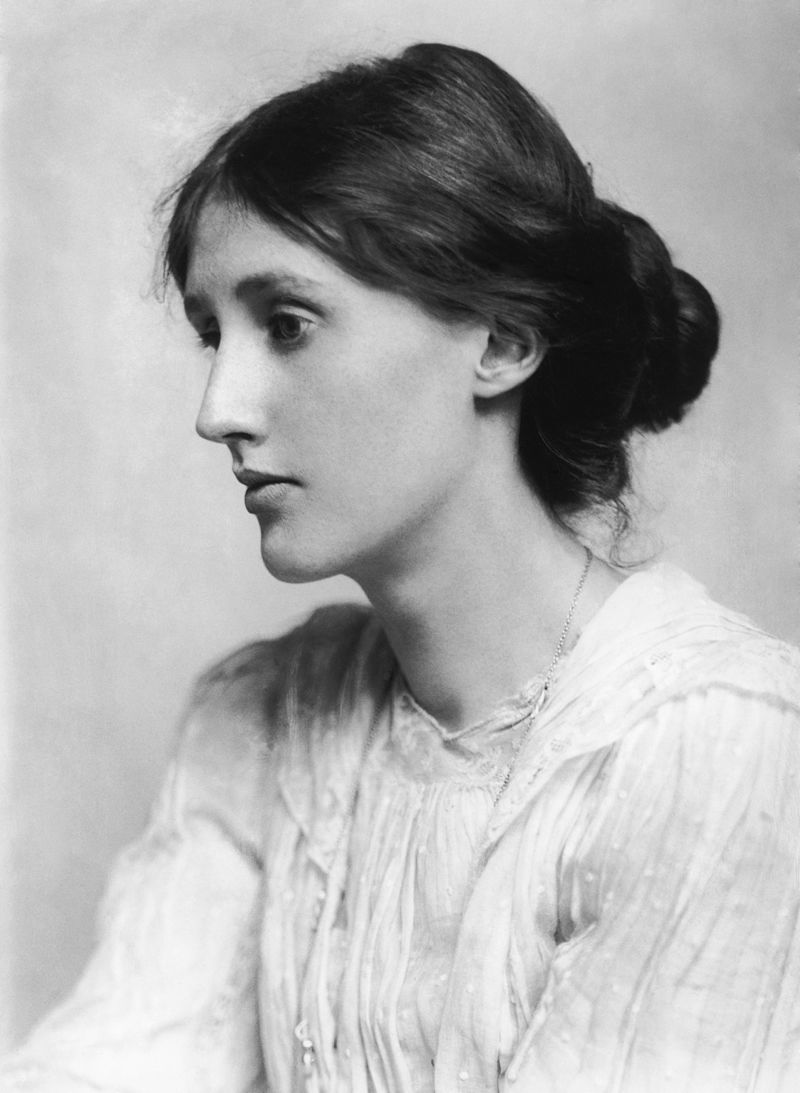

At its core, this brazen escapade was the brainchild of Horace de Vere Cole, a well-known prankster of his day, who along with a group of friends known as the Bloomsbury Group, including the yet-to-be-famous Virginia Woolf, managed to dupe the Royal Navy into giving them a grand tour of HMS Dreadnought, Britain’s most advanced battleship, while posing as Abyssinian royalty. As I delved into various publications and accounts of this event, I found myself not only smiling at the sheer absurdity of this prank but also appreciating how it exposed the cracks in Edwardian society and also British imperial pride.

The Mastermind: More Than Just Prankster

Horace de Vere Cole wasn’t your average prankster. Known in London society for his elaborate public stunts, Cole seems to have had a particular talent for exposing the snobbishness of the upper classes. His pranks ranged from Whoopi cushions at society dinner parties to the more elaborate, such as standing in the middle of Piccadilly Circus dressed as the Sultan of Brunei.

For the Dreadnought Hoax, Cole assembled an unlikely crew. Virginia Stephen (later Woolf) was then a 28-year-old aspiring writer, known more for her sharp wit than her literary prowess. Her brother Adrian Stephen, the black sheep of the family, was always up for a laugh. Rounding out the group were Duncan Grant and Guy Ridley, artists whose skills would prove crucial in the visual presentation of the deception.

What fascinates me about this group is how their backgrounds in art and literature may have influenced their approach to the prank. It wasn’t just about fooling the Navy, it was an early form of performance art aimed at challenging the very notions of identity and authority that underpinned Edwardian society.

HMS Dreadnought: More Than Just a Ship

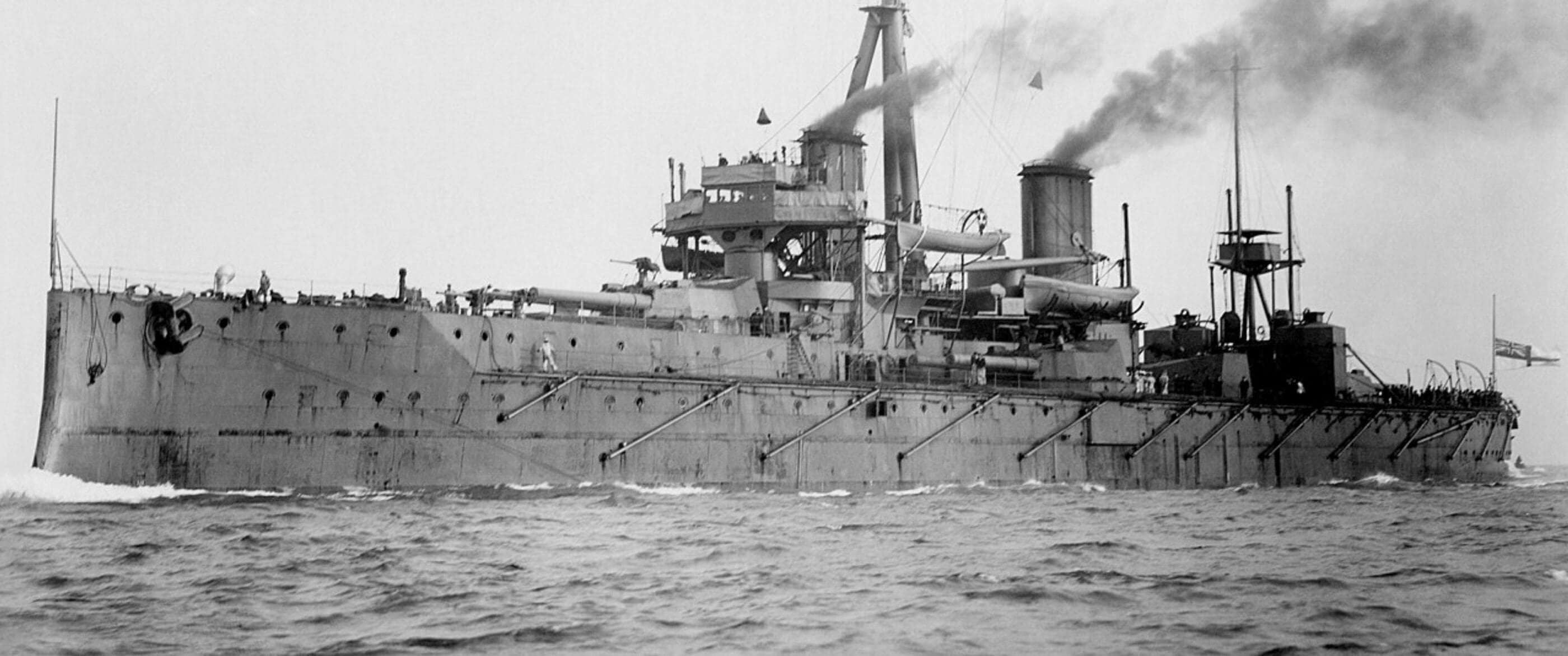

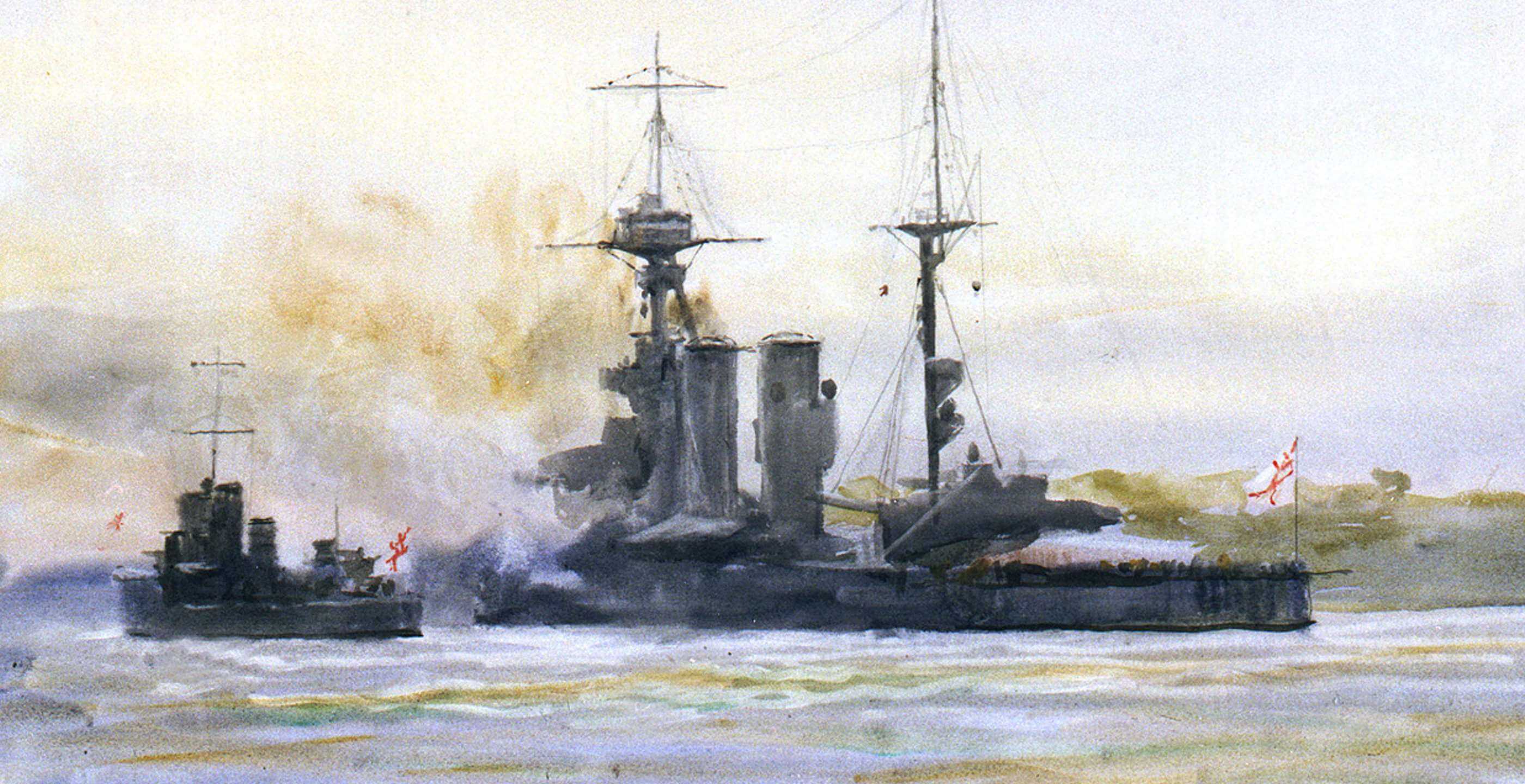

To fully understand Cole’s chosen target, we need to understand what HMS Dreadnought represented in 1910. Launched just four years earlier, this battleship was a floating embodiment of British naval supremacy. With its revolutionary design heavy armament and steam turbine engines, Dreadnought when launched rendered all other nations naval battleships obsolete overnight.

Here is a correspondences account from the Times printed in 1906.”As the HMS Dreadnought emerged from the mist, her sheer size and unprecedented armament left us awestruck. Her sleek profile and towering guns seemed to redefine naval power in an instant. Never before had such a vessel appeared on the seas, marking anew era in naval warfare.”

It is set against this backdrop that makes Cole’s and the Bloomsbury Groups choice of target all the more poignant. By infiltrating the pride of the Royal Navy, the group wasn’t just embarrassing a few naval officers, they were poking fun at the very fabric of British imperial confidence.

The Plan: Absurdity Meets Meticulous Detail

The genius of the plan lay in its blend of the ridiculous and the plausible. The idea of impersonating Abyssinian royalty might seem an odd choice today, but in 1910, Ethiopia (then known as Abyssinia) was one of the few African nations to successfully resist European colonization. Its royal family held a certain mystique in the eyes of the British public.

The attention to detail was impressive. The group invented a language that was a mishmash of Swahili, Greek, and Latin, peppered liberally with nonsense words. The artists Duncan Grant and Guy Ridley together came up with the costumes and face paints. The group even went so far as to request that all white objects be removed from sight during the tour, claiming it was taboo in their culture, a clever ruse to prevent them from having to sign the visitor’s book.

Virginia Woolf later wrote in her diary, “Never have I seen such a sight as the officers of the Dreadnought bowing and scraping to us, desperately trying to make sense of our gibberish.” The absurdity of the situation clearly stuck with her, influencing her later explorations of identity and perception in novels like “Orlando.”

The Execution: And So It Begins

And so, it began. Cole, posing as “Herbert Cholmondeley” of the Foreign Office, sent a formal telegram to the Royal Navy requesting a tour of HMS Dreadnought for the Abyssinian delegation. The Royal Navy, eager to impress important guests, hastily arranged for a special train to transport the “princes” from London to Weymouth.

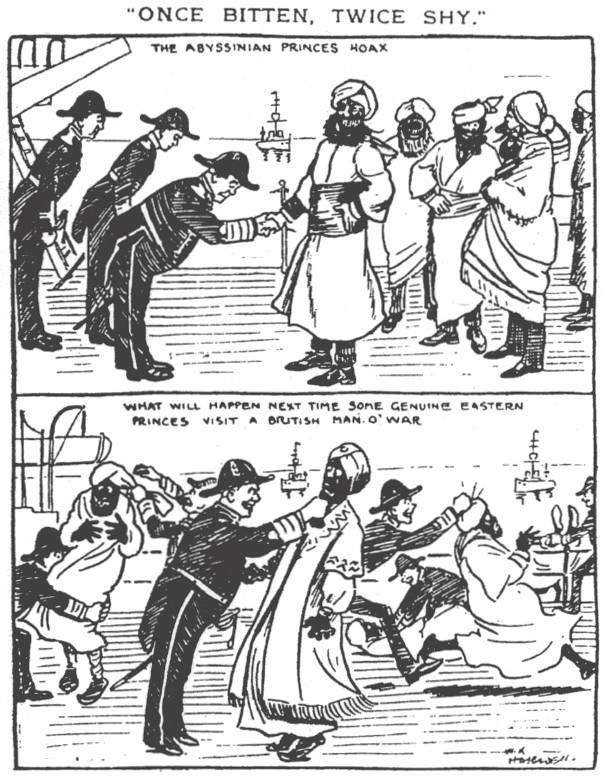

On February 7, 1910, the group boarded the special train to Weymouth, where HMS Dreadnought was docked. Eyewitness accounts describe a scene of the arrival of the Abyssinian delegation at Weymouth station as carefully orchestrated chaos. The “princes,” resplendent in flowing robes and turbans, with their faces darkened by makeup, were greeted with full military honours. The Navy band, caught off guard by the hastily arranged visit, played the national anthem of Zanzibar, apparently the only “African” tune they knew. No one seemed to notice or care that Zanzibar and Abyssinia were entirely different countries, thousands of miles apart.

As the tour of ship went ahead, the royal delegation maintained their façade with diligent commitment. Duncan Grant, acting as the interpreter, would solemnly translate the naval officer’s explanations of the ships working into the groups made-up language, eliciting enthusiastic cries of “Bunga! Bunga!” This phrase, which became synonymous with the hoax, was apparently inspired by a character in a popular children’s story of the time.

One officer, perhaps sensing something amiss, allegedly muttered to a colleague, “I could swear I’ve seen that tall fellow at the Gaiety Theatre.” Not knowing in a few days’ time, he would be proven right.

The Aftermath: Laughter and Lesson

A few days later, an anonymous letter was received the Daily Mirror, revealing the visit to be a prank, this sent shockwaves through British society. The Admiralty was furious, the public was amused, and the pranksters were briefly concerned about potential legal action. In researching this article, I came across a little-known fact that highlights the Navy’s embarrassment.

Apparently, some sailors were ordered to scrub the deck where the “Abyssinian princes” had walked, which can only be interpreted as a symbolic attempt to cleanse the ship of the perceived slight. The incident sparked a broader debate about security and protocol in the armed forces. Questions were raised in Parliament, and there were calls for Cole’s prosecution. However, as one witty MP reportedly quipped, “If we start arresting everyone who makes fools of us, we’ll have to lock up half the opposition.”

The Legacy: More Than Just a Laugh

While the Dreadnought Hoax is often remembered as a brilliant prank, its significance run deep. It exposed a system built on rigid hierarchies and unquestioning deference to authority. The ease with which Cole and the Bloomsbury group managed to gain access to one of Britain’s most secure military assets, revealed uncomfortable truths about the assumptions underpinning imperial power.

For Virginia Woolf, the experience seemed to bring about themes she would explore throughout her literary career; the fluidity of identity, the performance of social roles, and the absurdity of societal conventions. In her 1928 novel “Orlando,” the protagonist’s ability to change gender and move through the centuries could possibly echo her experience of becoming an “Abyssinian prince” for a day.

The phrase “Bunga Bunga” took on a life of its own, entering the English language as a shorthand for absurd or nonsensical behaviour.

Conclusion: A Prank for the AgesAs I reflect on the Dreadnought Hoax over a century later, I’m struck by its timelessness. It’s a tale that combines the best elements of farce, mistaken identities, elaborate disguises, bumbling authority figures, with a sharp satirical edge. Cole and his friends didn’t just pull off a great prank, they delivered a masterclass in the power of creativity to poke fun and highlight some of the absurdities and class structure in British society. Today in an era of “fake news” and online hoaxes, the Dreadnought incident reminds us of the thin line between appearance and reality, authority and subversion, is nothing new. It stands as a testament to the enduring human desire to have fun and find humour in the most unlikely of places, even on the deck of the world’s most formidable battleship.

As Virginia Woolf herself might have said, sometimes it takes a little bit of “Bunga Bunga” to shake up the world.

Richard Clements is an avid amateur historian and writer with a passion for uncovering and reviving unusual and overlooked stories from history. He aims to bring these narratives to a wider audience, giving them a new lease on life. Richard has authored various articles on a broad range of topics, contributing to multiple online publications that explore history’s many mysteries.

Published: 14th June 2024