In 1815, the long wars with Revolutionary France finally came to an end with the defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte at the Battle of Waterloo. Britain was to emerge from this period as the most powerful colonial and commercial nation in Europe, but in the immediate post-war years, when import barriers were lifted and continental goods flooded the markets, there was a severe economic slump. The downturn was exacerbated by the demobilisation of around 350,000 soldiers and sailors, causing unemployment levels to soar.

The government’s introduction of a Corn Law in 1815 did nothing to help the poorer classes. The new law was designed to protect British farmers by banning the importation of cheap grain from abroad. The removal of competition forced up the price of domestic grain; in rural East Anglia, the average price of wheat rose precipitately between February and May 1816, from around 54 shillings a quarter to around 77 shillings.

Caricature of the Prince Regent

Caricature of the Prince Regent

The contrast between the poverty in the countryside and the continued extravagance of the royal family added insult to injury. While the poor were being told that their only option was to resign themselves with Christian fortitude to want and hunger, the Prince Regent was spending money like water, redesigning and redecorating the Royal Pavilion at Brighton – between 1814 and 1820 the bills for the project totalled a staggering £155,000. In early 1816, Parliament voted a lump sum of £60,000 to the Regent’s daughter, Princess Charlotte, on her marriage to Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld.

The poorer classes had no access to political power or legal redress, and were forced to resort to protest to make their voices heard in hard times. Food riots were not uncommon. The aims of the protestors were usually local and specific. In times of high prices and hunger, they hoped to force the authorities to bring down the price of wheat or bread. Occasionally, they would seize the foodstuffs themselves, to sell on to the community at an affordable price. The protests were often successful; the authorities would either agree to the demands, or look for a compromise solution.

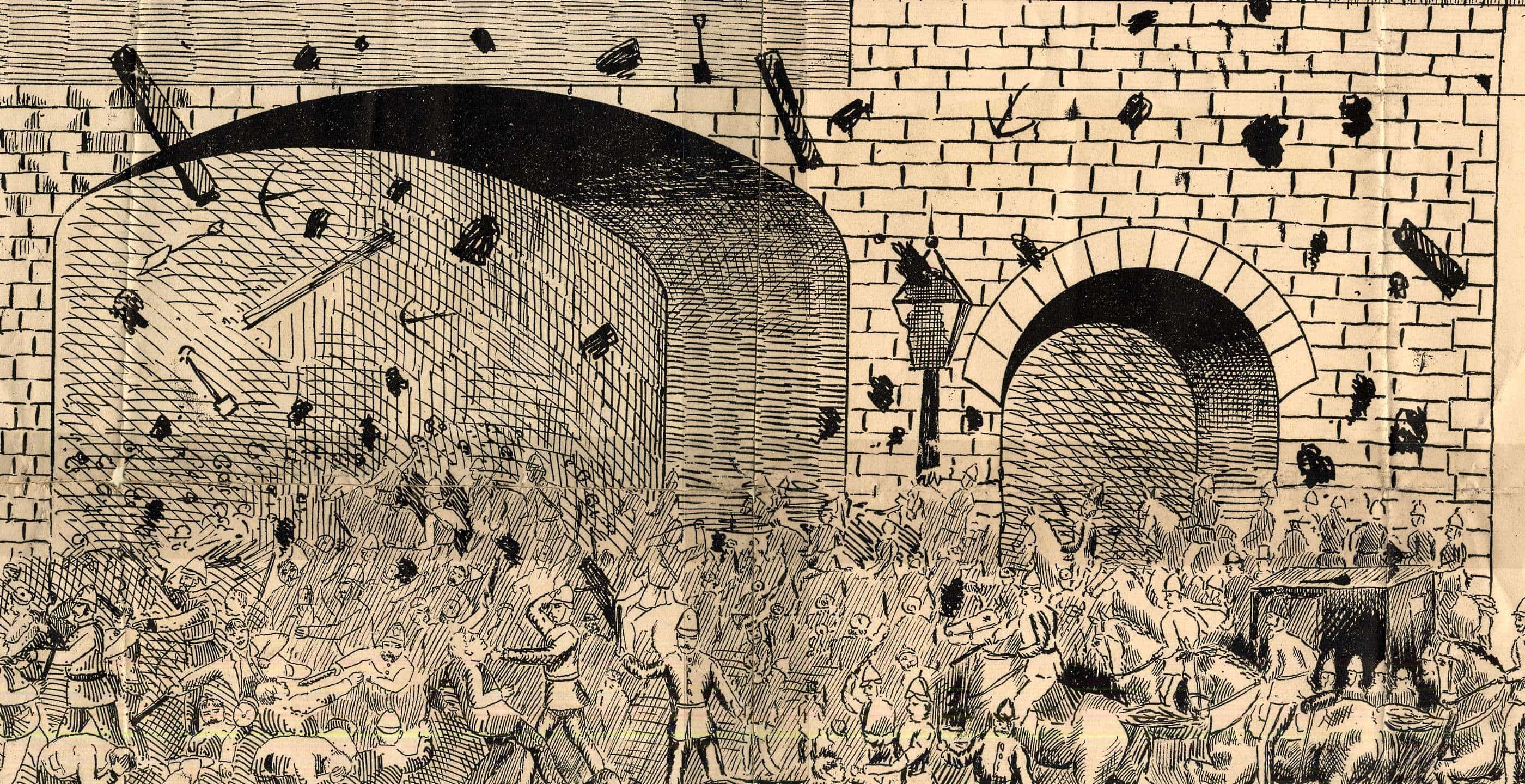

In the late spring of 1816, the anger and desperation in East Anglia erupted into riots. The largest of the disturbances took place in the neighbouring towns of Littleport and Ely. The riots began on the evening of 22 May, when a large group of labourers congregated at the Globe Inn in Littleport to demand a rise in wages and a decrease in the price of flour. The situation quickly grew out of hand as the men began to target the houses and businesses of individuals who they felt were responsible for their plight: the local vicar, the overseers of the poor, millers, farmers and shopkeepers.

The angry crowd, armed with clubs, sticks and iron bars, went from door to door forcing householders to hand over money as a ‘contribution’ to their cause. As the evening went on and some of the crowd continued drinking, their behaviour became rowdier. Demands for money were increasingly accompanied by assault, theft, and the destruction of goods and furniture. Old age and frailty were no protection: the rioters assaulted a retired farmer in his seventies and his wife, before stealing a hundred guineas from him and ransacking his home for valuables. The Littleport vicar, with his wife and invalid daughter, had to flee his house, which was subsequently wrecked by the rioters.

The men decided to march on Ely the next day, to demand concessions from the magistrates there. They armed themselves for this encounter with guns, gunpowder and shot, as well as pitchforks, cleavers and bludgeons. Their most fearsome-looking weapon, a farm wagon on which they had mounted four large fowling-piece guns, resembled a primitive tank.

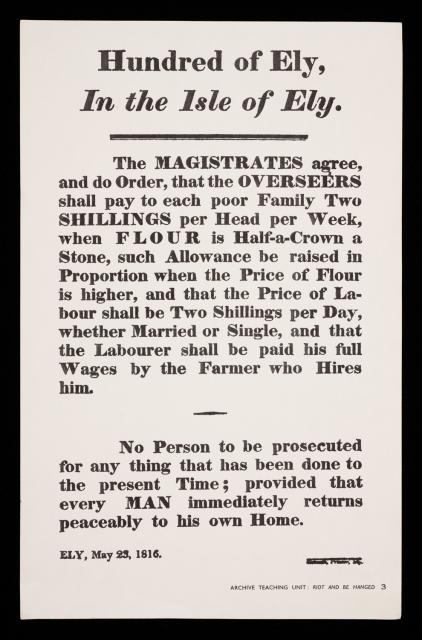

The Ely magistrates, finding themselves surrounded by a threatening, armed crowd, capitulated quickly. They issued a proclamation promising a raise in wages and a cap on the price of wheat. They also promised that, if the men went quietly home, no one would be prosecuted for any crime committed up to that point – an assurance that, as was later pointed out, they were not legally empowered to give. Some of the protestors returned to Littleport, but others, emboldened by this success, continued drinking and rioting in Ely.

The terrified magistrates sent an urgent message to the Home Secretary, Lord Sidmouth, reporting the ‘alarming and dreadful state of our district’ and begging for ‘the most powerful assistance’. The government’s only option was to send in the military – there was no police force in England until 1829. Detachments of the 1st Royal Dragoons, the Royston Yeomanry, and the Cambridgeshire militia were despatched to Ely.

The protestors had no chance. Soon after the arrival of the soldiers there was an exchange of shots between the military and the mob. A dragoon and several rioters were wounded in the melee, and one protestor, a labourer called Thomas Sindall, was killed while running away after trying to wrest a gun from a trooper. At the subsequent inquest, his death was as recorded as ‘justifiable homicide’. The rioters fled, pursued by the troops on horseback. By that evening, eighty-six men had been rounded up and placed in custody. The trials of those involved in the most serious crimes took place a month after the riots.

Although food riots had been common throughout the century, the authorities’ response to crowd protest had begun to change in the aftermath of the French Revolution. The government suspected popular disturbances of being politically motivated, and having wider aims than the traditional restoration of fair prices. The unusual level of violence at Ely and Littleport was seen as particularly alarming. Consequently, the trials were seen as events of national importance, and government ministers were determined to make a public example of the worst offenders, to scotch what they feared was a growing revolutionary threat.

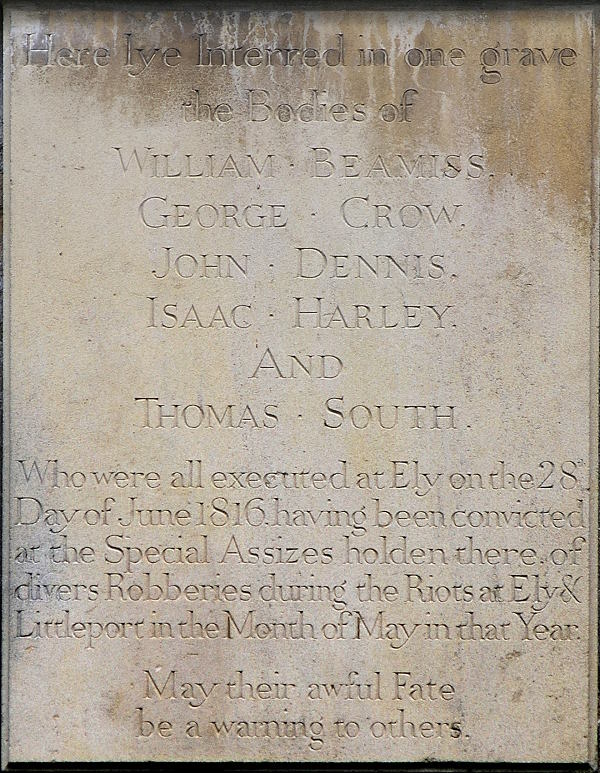

The trials were held in Ely, at a special Assizes, with two judges sent down from London to preside in conjunction with the Isle’s Chief Justice. The cases tried at the Assizes consisted principally of robberies and thefts, which were capital crimes. Thirteen charges were heard over a five-day period. Twenty-four of the defendants were initially sentenced to death, although nineteen were later reprieved. Nine of the reprieved were transported, and ten were given a term of imprisonment in Ely gaol. The remaining five were condemned to hang: William Beamiss, George Crow, John Dennis, Isaac Harley and Thomas South.

The executions of the five men were scheduled to take place on Friday 28 June. The occasion was deliberately orchestrated to provide an impressive and solemn spectacle: three hundred ‘gentlemen of Ely’ accompanied the magistrates on horseback to the place of execution, carrying white wands and accompanied by a band of constables who had been specially sworn in for the occasion. The condemned men were brought to the place of execution in a cart with raised seats covered in black cloth. They were hanged in front of a crowd of their neighbours, friends and families.

Although they were from Littleport, the hanged men were buried in Ely in a communal, unmarked grave in St Mary’s churchyard. A wooden plaque was fixed to the tower of the church, recording their names with the comment, ‘May their awful Fate be a warning to others’.

Elaine Thornton is a writer and the author of a biography of the opera composer Giacomo Meyerbeer, Giacomo Meyerbeer and his Family: Between Two Worlds (Vallentine Mitchell. 2021).

Published: 7th November 2023.