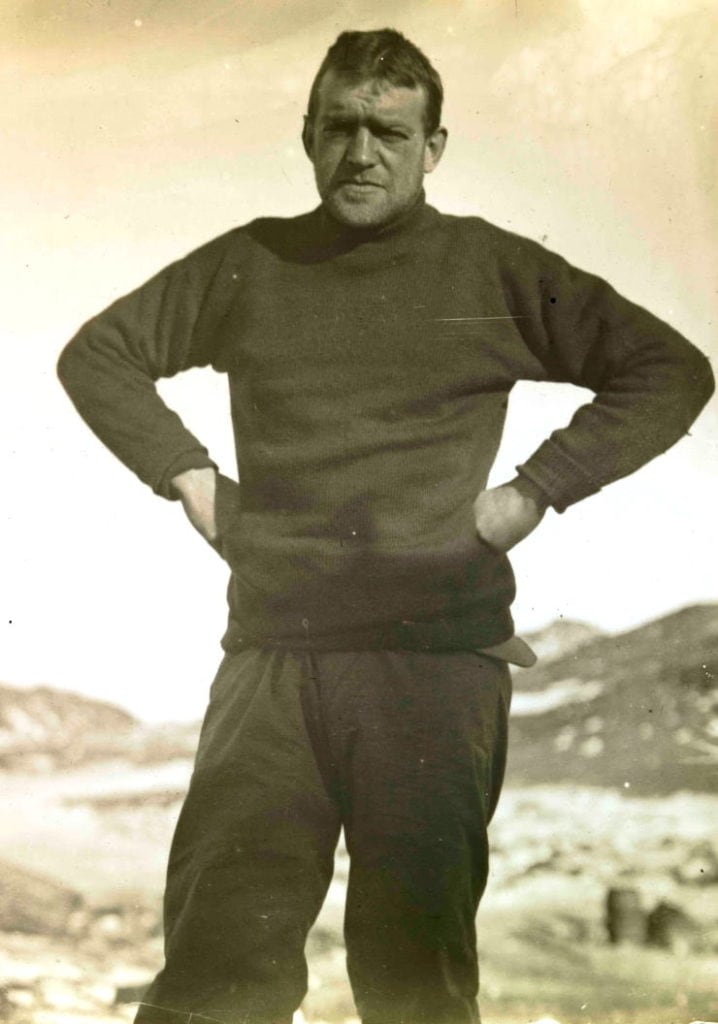

Sir Ernest Shackleton, the intrepid explorer, is best remembered for embarking on a fateful voyage aboard the Endurance in a bid to cross the Antarctic.

An Anglo-Irish adventurer, he became a pivotal figure in the era later characterised as the “Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration”, thanks to the laudable and ambitious efforts of Shackleton and others like him.

In August 1914, against a backdrop of war in Europe, Shackleton embarked on an expedition to the Antarctic which almost cost him his life.

His ability to survive and keep the rest of his crew safe whilst stranded for two years still remains a remarkable story celebrating his heroism and leadership.

Shackleton’s early life began in February 1874, born in County Kildare in Ireland, the second of ten children. His family soon uprooted and moved to London where Shackleton grew up.

Intent on following his own path, at the age of sixteen he joined the Merchant Navy, subverting his father’s wishes for him to attend medical school. By the age of eighteen he had already achieved the rank of First Mate and only six years later was a certified Master Mariner.

His time in the Navy proved to be an enlightening experience for an adventurous young man like Shackleton as he was able to explore and expand his horizons, ultimately spurring him on to achieve greater goals.

In 1901, he joined his first expedition to the Antarctic, led by the esteemed British naval officer Robert Falcon Scott. The journey involved a challenging trek to the South Pole and was a joint venture with the Royal Society and the Royal Geographical Society.

Referred to as the Discovery Expedition, named after the ship, Scott and his team embarked on their voyage on 6th August 1901 with much support from King Edward VIII.

The venture had various aims, some of which were scientific and motivated by the Royal Society’s involvement, whilst other goals were simply exploratory. Of the latter, a major accomplishment was about to follow as a trek to the South Pole took Scott, Shackleton and Wilson to a significant latitude, only around 500 miles away from the pole. This was a marvellous achievement, the first of its kind, however the journey back proved too much for Shackleton.

On the brink of physical exhaustion, his body could not take any more of the gruelling challenges and he was forced to leave the expedition early and return home.

When he returned to England, Shackleton made a major career move: after serving so long in the Navy, he decided to embrace a career in journalism instead.

In the space of a few years he also made an unsuccessful attempt to become a Member of Parliament as well as serving as part of the Scottish Geographical Society.

Whilst he pursued many different ventures, the expedition to succeed in reaching the South Pole was still very much on his mind.

In 1907 he made a second attempt to achieve this goal, this time reaching a location which took him almost within 100 miles of his target. Leading his own group on the ship “Nimrod”, Shackleton and his men were able to climb Mount Erebus before being halted due to poor conditions and forced to return.

As part of his expedition, important scientific data had been accumulated, earning Shackleton a knighthood on his return to England.

Nevertheless, only a few years later Shackleton was disappointed to discover that his dream of reaching the South Pole had already been accomplished by another, a Norwegian explorer by the name of Roald Amundsen.

This achievement was followed by his former commander, Robert Scott who also reached the South Pole but sadly lost his life on the return home.

Whilst this success proved to be a blow for Shackleton both professionally and personally, his desire to explore remained undeterred. Forced to rethink his aims, his new goal was even more ambitious: to cross the continent of Antarctica.

So the date was set; in 1914 Shackleton made his third trip to the Antarctic as part of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition aboard the ship “Endurance”. The brainchild of Shackleton, his determination to create a lasting legacy of exploration was at the heart of this ambitious project to make the first land crossing of the Antarctic.

The task for Shackleton and his men was a daunting one and required a great deal of preparation. The plan was to sail to the Weddell Sea and land near Vahsel Bay where they would embark on a march across the continent via the South Pole.

Unable to achieve these goals in just one group, an additional party of men would set up a camp in McMurdo Sound from where a series of depot spots would be set up in order to ensure enough supplies to sustain the trekking party throughout their journey.

Two ships were used: Aurora, for the supply depot team and Endurance, a three mast sailing vessel for Shackleton and his intrepid voyagers. The ship was built and completed in 1912 in Sandefjord by the master shipbuilder Christian Jacobsen who would ensure that the ship was built for durability.

Map of the routes of the ships Endurance and Aurora, the support team route. Red: Voyage of Endurance. Yellow: Drift of Endurance in pack ice. Green: Sea ice drift after Endurance sinks. Dark Blue: Voyage of the lifeboat James Caird. Light Blue: Planned trans-Antarctic route. Orange: Voyage of Aurora to Antarctica. Pink: Retreat of Aurora. Brown: Supply depot route

Map of the routes of the ships Endurance and Aurora, the support team route. Red: Voyage of Endurance. Yellow: Drift of Endurance in pack ice. Green: Sea ice drift after Endurance sinks. Dark Blue: Voyage of the lifeboat James Caird. Light Blue: Planned trans-Antarctic route. Orange: Voyage of Aurora to Antarctica. Pink: Retreat of Aurora. Brown: Supply depot route

On 1st August 1914, just as war loomed on the horizon, Shackleton and his twenty-seven man team departed from London and set sail on this intrepid trip to the South Pole and beyond.

In just a couple of months, the ship reached South Georgia in the southern Atlantic which, unbeknown to Shackleton and his crew, would be their last time on dry land for almost five hundred days.

On 5th December 1914, they continued on their scheduled journey, however their strategy of reaching their next base was thrown up in the air when they became trapped by pack ice in the Weddell Sea before they had a chance to reach their intended station at Vahsel Bay.

As the situation worsened, the ship was crushed by the ice and began to drift in a northerly direction.

As the ship began to sink, Shackleton and his crew were forced to accept their fate, stranded on a sheet of ice in the brutal Antarctic winter of 1915.

With the ship eventually sinking into the depths, Shackleton and his crew now set up in camps on precarious sheets of ice.

After months of surviving in such unimaginable circumstances, in April 1916 Shackleton embarked on a mission to escape and reach land. A dangerous and risky endeavour, he led his men with a resolute bravery despite all the obvious obstacles to their survival.

The crew embarked on this voyage, leaving the ice sheets and crowding into three small boats in order to reach the intended destination of Elephant Island, a mountainous island in the outer reaches of the South Shetland Islands.

Eventually, after seven treacherous days at sea, the crew arrived safely at their destination. Whilst thankful to be stepping on firm ground, they were still no closer to being rescued on such a remote and uninhabited island, far away from any other human life.

With little prospect of surviving on the island, Shackleton took matters into his own hands and set out once more in one of his small lifeboat vessels with five of his men in order to find help.

Miraculously, the vessel and its occupants managed to navigate back towards South Georgia and in sixteen days reached the island in order to ask for assistance.

Now closer than ever to having a rescue mission come to the aide of his men, Shackleton made one final trip across the South Georgia island to where he knew a whaling station was positioned.

From this new location and with help now in tow, Shackleton did not let his men down and launched a successful rescue mission to Elephant Island where the rest of his crew were waiting.

Rather remarkably, none of the twenty-seven man team or Shackleton died in these treacherous circumstances. In August 1916 a rescue mission recovered the “Endurance” men from Elephant Island and all were safely returned home.

As for the rest of the Trans-Continental team, the supply depot party had also run into trouble with the ship Aurora but continued to lay the supplies nonetheless. Eventually, needing rescue, the party of men sadly lost three lives in the process.

Whilst the trans-continental trek was not achieved, Shackleton had accomplished a feat perhaps even more impressive. The ability to save and protect his men, living on ice sheets for months, sailing in a small boat for sixteen days across an ocean and trekking across an island to organise a rescue, the success story was their survival.

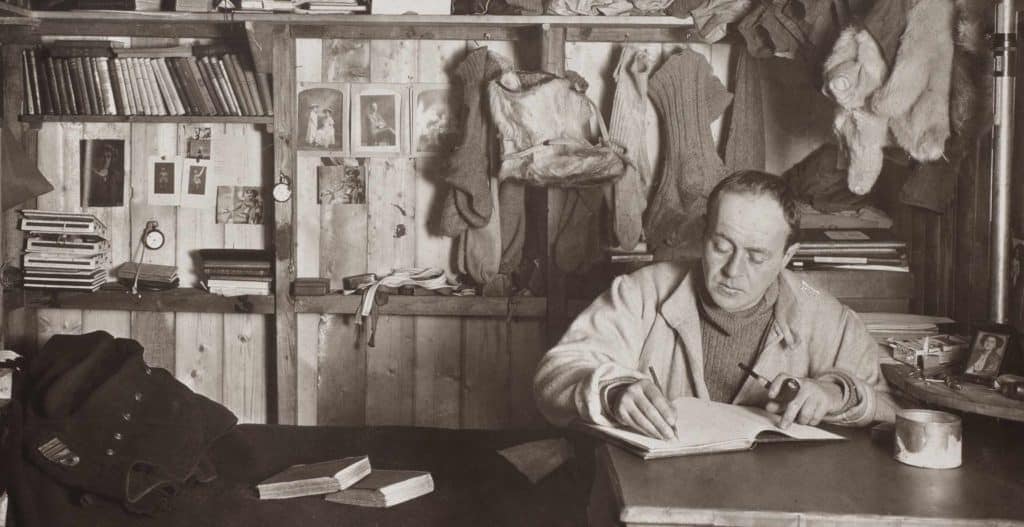

In 1919 Shackleton recorded the accounts of this remarkable endeavour in his book “South” which documented the unbelievable and astonishing story.

Living for seventeen months on ice, fending off disease, escaping predators and ensuring the survival of the entire crew was destined to be the legacy left behind by Shackleton.

In 1921, once again he set off to accomplish his dreams of exploration: sadly, this fourth expedition was to be his last as he died of a heart attack in January 1922.

Whilst Shackleton did not fulfil his ultimate goal, his successful rescue mission was much more epic than anyone, including himself, could have ever imagined.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 5th August 2020.