In the spring of 1839, the British Army of the Indus marched from India through the Khyber and Bolan passes of the Hindu Kush mountains and into Afghanistan, to replace the Afghan leader Dost Mohammad Khan with a figure who would benefit the long-term security of Britain’s grasp on India. After replacing Dost Mohammad in the summer of 1839 with Shah Shuja, who had himself been replaced by Khan in 1809, Britain maintained a garrison in Afghanistan until late 1841, when it was forced to leave following the increasing discontentment felt towards the occupation by the native population.

The subsequent retreat from Kabul in December of 1841 and January of 1842 was one of the most shocking failures of modern British military history, with only a small number of the original 16,000 soldiers and camp attendants surviving the retreat to Peshawar.

The decision to invade Afghanistan was announced by the British Governor-General of India, Lord Auckland in the Simla Manifesto of October 1838, and was based upon several reasons. From the early 19th century onwards, Britain and Russia had been embroiled in a diplomatic cold war over the lands of Central Asia, which formed a buffer zone between Tsarist Russia and the ‘jewel in the crown’ of the British Empire, India. ‘The Great Game’ as it has come to be known, involved the territories of modern-day Iran, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, which were all witness to spying and scheming from both Britain and Russia.

Following the joint Russo-Persian siege of Herat in western Afghanistan in 1837-1838, the British high command in India believed it to be of the utmost importance to have an Afghan regime that would protect British India – Dost Mohammad was considered to have been in league with Russia throughout the 1830’s. Alongside the Russian threat, Britain valued the importance of its allyship with the Punjabi Kingdom of Ranjit Singh, who also preferred Shuja to Khan as ruler of Afghanistan – as evidenced by the Tripartite Treaty between Britain, Shuja and Singh in 1838. Afghanistan and Singh’s Kingdom had skirmished intermittently throughout the 20 years that preceded the war, and so the British decision to enter Afghanistan was founded upon both its desire to protect India from a potential Russian invasion, and to placate the Sikh Kingdom which bordered British India.

The British expedition entered Afghanistan in the spring of 1839, and after a series of short, successful conflicts, such as the Battle for Ghazni, Dost Mohammad was forced to flee the capital of Kabul in the summer of 1839, whereupon Shuja promptly took up his position as de facto leader of Afghanistan. Khan fled but reconvened with a number of loyal troops in late 1840 to face the British forces once again. Despite defeating British cavalry at Parwan Darra, Dost Mohammad Khan surrendered on 2nd November 1840, where he was taken into captivity in India until 1842.

However, although the British had ostensibly overseen Afghanistan through the puppet leader Shuja since the summer of 1839, their hold on power was exceedingly precarious. Discontentment grew throughout 1840 and 1841 with both Shuja’s reign and the British occupation. Rising taxes were needed to fund the Shah’s opulent lifestyle and inflation arose due to the increased demand for foodstuffs which was derived directly from the need to feed the occupying soldiers, and so the British soon became unpopular with the local population. The drinking and licentiousness of the occupying forces further inflamed the Islamic population, the political agent Alexander Burnes being an infamous offender in this regard. Local clerics began to call for holy war (jihad) to dispel the occupying force.

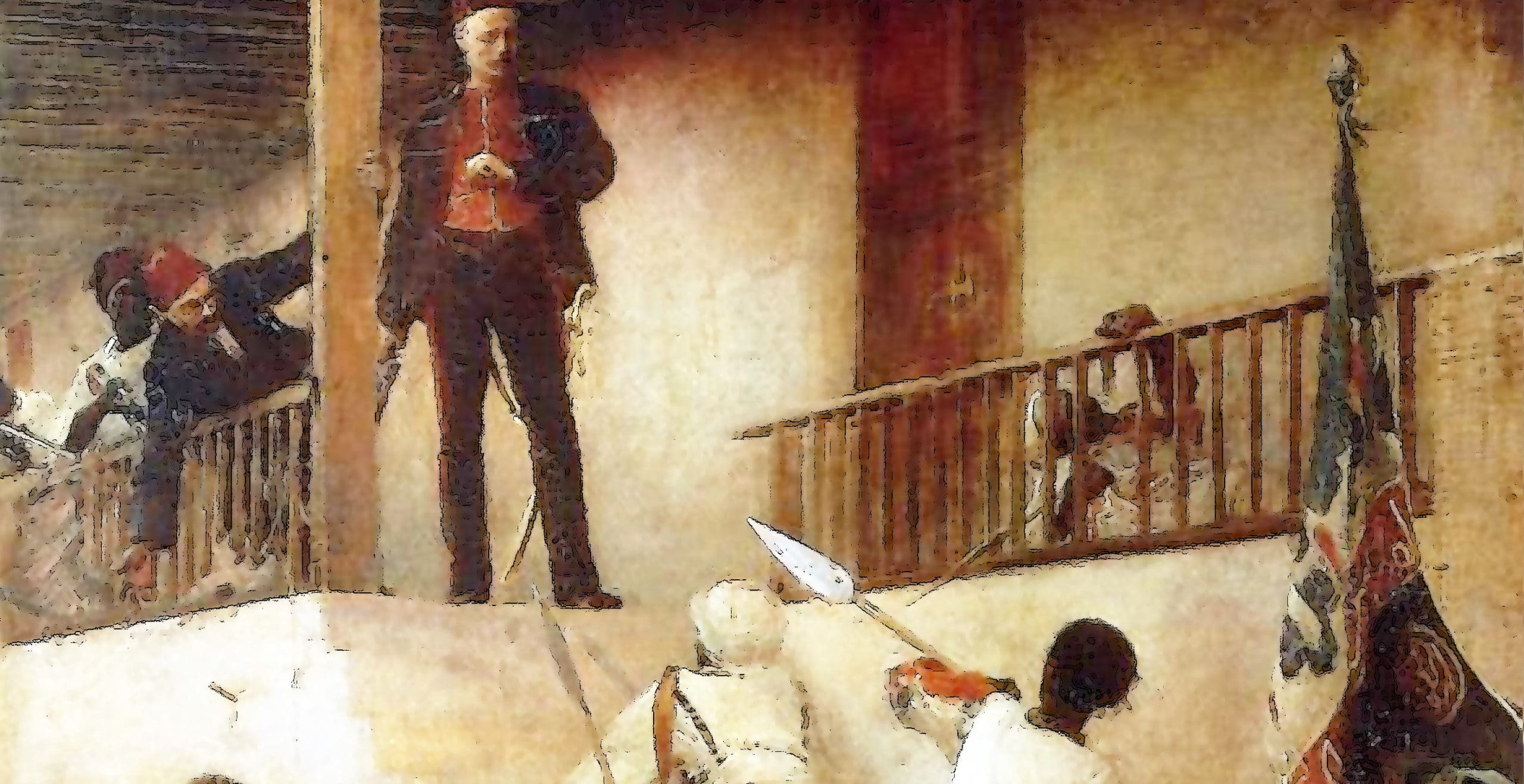

Opposition to British rule was successfully fomented by Akhbar Khan, the son of Dost Mohammad, following his father’s capture and on 2nd November 1841, an insurrection broke out in Kabul against the British occupation. This resulted in the death of Burnes, and so William Hay Macnaghten, another British political agent, was forced to negotiate the British withdrawal from Afghanistan in December.

However, as the troops, families and camp followers made their war to Jalalabad, Afghan tribesmen attacked and harried the force to the point of extinction; out of the 16,000 that left Kabul, a small number were taken hostage, and fewer still were able to make it alive to Jalalabad. The existence of British prisoners in Afghan hands justified a bloody-thirsty Army of Retribution that re-entered Afghanistan in the spring of 1842, to both retrieve the hostages and raze the Kabul bazaar, superficially allowing the British to claim the last word in an otherwise disastrous campaign. Shuja was later killed in Kabul and Khan returned to the throne, rendering the British efforts of the previous 4 years worthless.

Following the failures of 1839-1842, Britain chose not to enter into direct conflict with Afghanistan for the best part of 40 years, until the Second Anglo-Afghan War of 1878-1880, with the inaugural colonial failure perennially haunting successive British, Soviet and American invasions.

Similarly, the unsuccessful campaign struck at the heart of British pretensions to worldly superiority and colonial stability, and so the accumulated failures of 1839-1842 had consequences that echoed into the Indian Sepoy Mutiny of 1857. Rather than stabilising the North-Western Frontier of India, Britain antagonised a dangerous foe whilst internally weakening the symbolic infrastructure that allowed them to control swathes of the world. The war was resultantly described by a contemporary as a ‘war begun for no wise purpose’ and concluded with no obvious success.

By Nye Owen. Nye Owen graduated with a 1st class degree in History from the University of Sheffield in 2022. He is currently working on further projects.

Published: 9th January 2023.