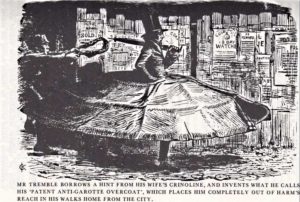

In December 1856, a cartoon in the British humorous magazine Punch suggested a novel use for the new-fangled crinoline frame. Adapted to become Mr Tremble’s “patent anti-garotte overcoat”, it protected him from attack as he made his way home from the office. A would-be garotter reaches in vain to slip a scarf over Mr Tremble’s neck from behind as the frame thwarts him.

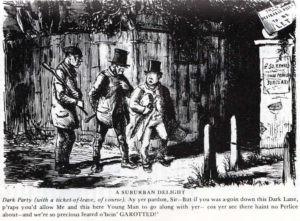

The Punch cartoon was an early comment on a “new variety of crime” that would grip the nation in a few years time. During The Garotting Panic of 1862, newspapers carried sensational reports on the terrifying “new” tactics employed by criminal gangs across the country. Even Charles Dickens was drawn into the debate about whether the crime of garotting was “un-British”, as The Times described it in November 1862.

In fact, garotting was not new, nor was it more “British” or “un-British” than any other crime. Some aspects of the modus operandi of garotting gangs would have been recognised by a member of the medieval or Tudor underworlds. Garotting gangs generally worked in groups of three, consisting of a “front-stall”, a “back-stall”, and the garotter himself, described as the “nasty-man”. The back-stall was primarily a look-out, and women were known to play this part.

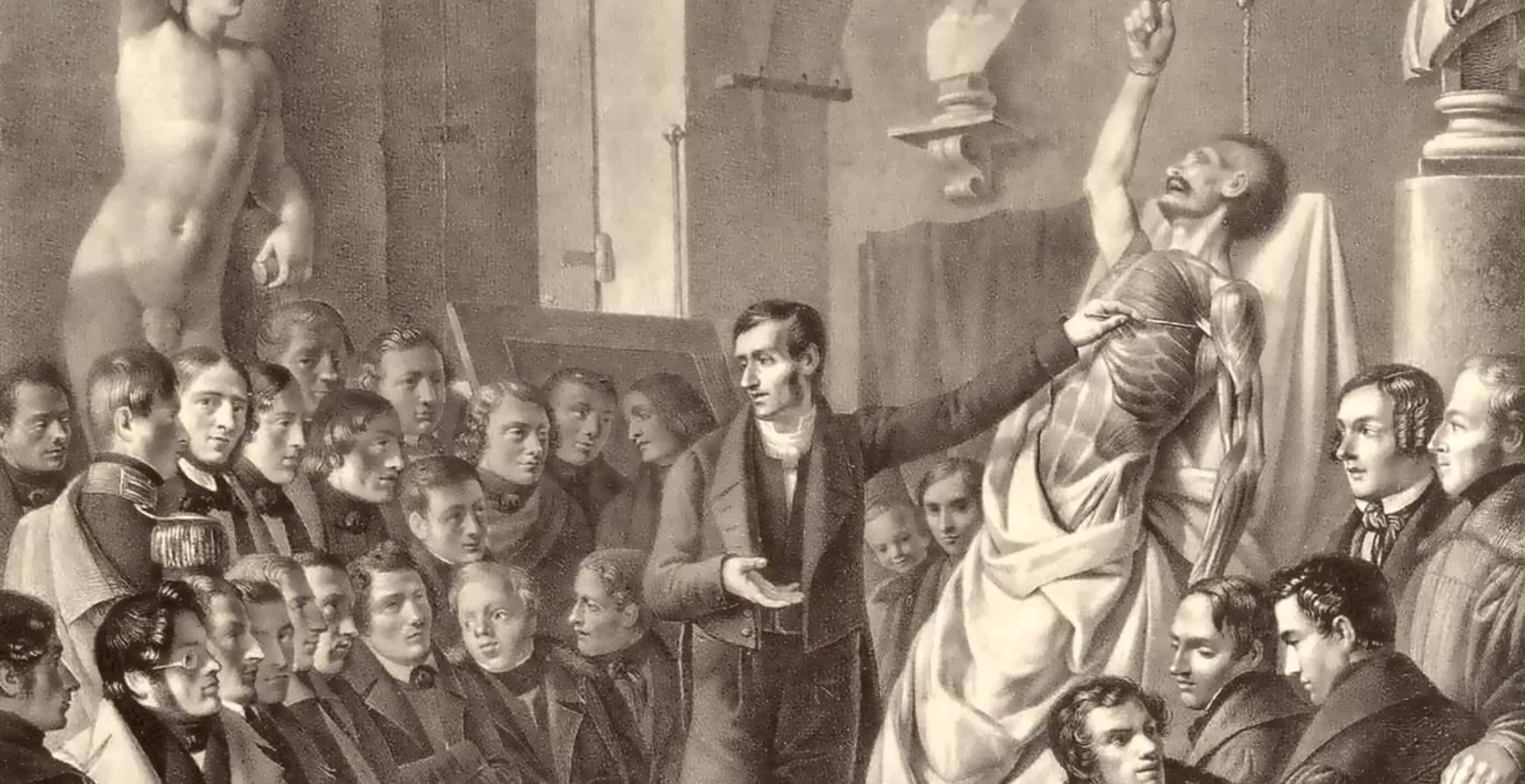

A brave correspondent of the Cornhill Magazine visited one criminal in jail to experience being a garotting victim. He described how: “The third ruffian, coming swiftly up, flings his right arm round the victim, striking him smartly on the forehead. Instinctively he throws his head back, and in that movement loses every chance of escape. His throat is fully offered to his assailant, who instantly embraces it with his left arm, the bone just above the wrist being pressed against the ‘apple’ of the throat”.

While the garotter held his victim in a choking grip, the accomplice quickly divested him of everything of value. Alternatively, the garotter simply stalked the victim silently, taking them completely by surprise as a muscular arm, a cord or a wire suddenly tightened round their neck. The hold was sometimes described as “putting the hug on”, and one of the aspects that concerned the press most was the way young boys – and in one instance, girls under the age of 12, allegedly – copied it. Some of the adult perpetrators are said to have learned it from their jailors while being transported or held on prison ships before being released back into the community.

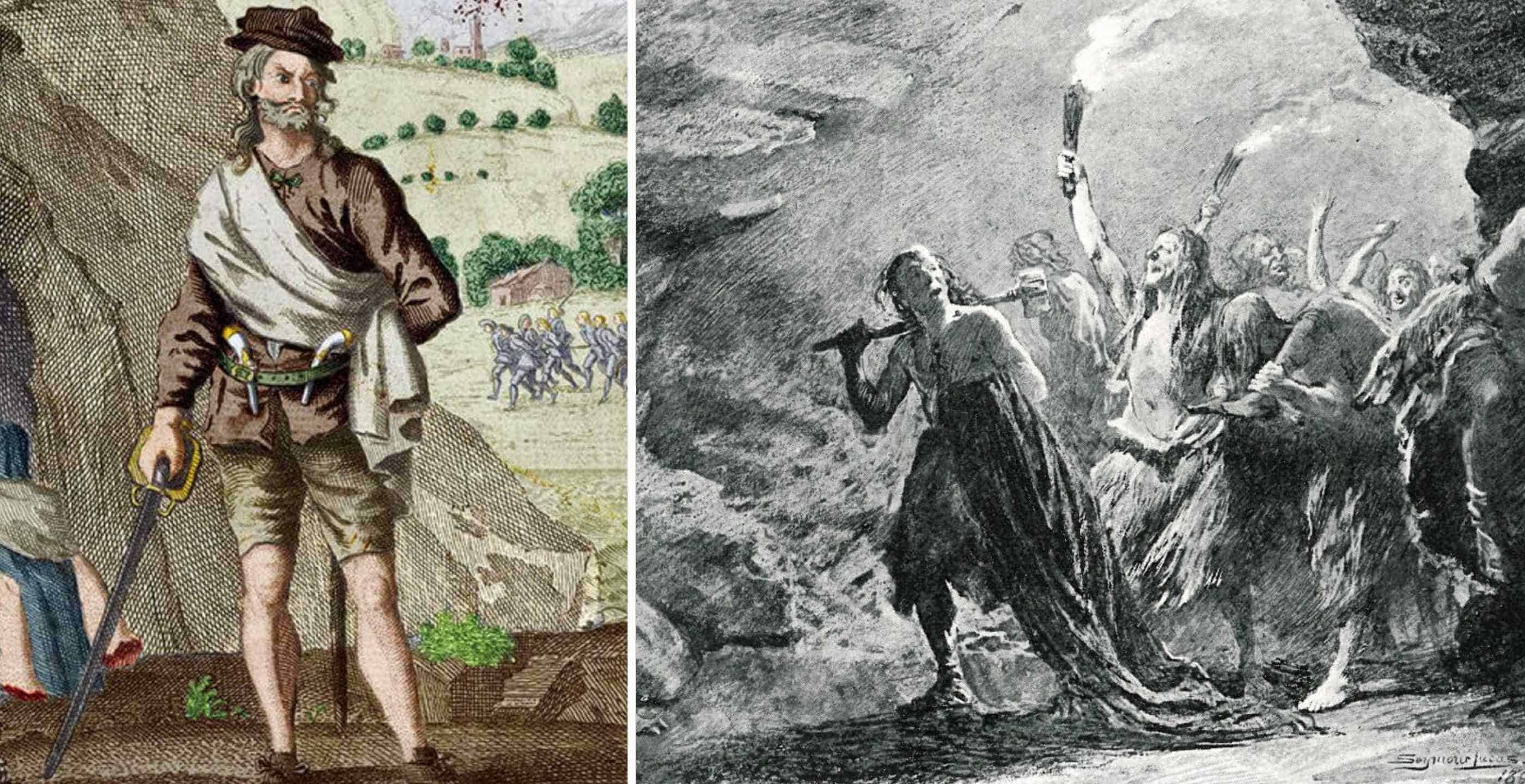

Bizarrely, while apparently suggesting that the crime held some sort of unnatural glamour for youngsters, The Times also compared garotting unfavourably to the dashing British highwayman and his “challenge and parley”. The Observer even went so far as to describe highwaymen as “gentlemanly” in comparison with the “ruffianly” garotter. What marked the one from the other was engagement in dialogue before the robbery, and physical contact. If press reports were to be believed, the British preferred to be robbed if the robbery was preceded by a cocked pistol and a “Stand and deliver!” rendered in a fashionable accent, rather than a choke and a grunt.

The idea that garotting was novel, un-English or un-British, and somehow the product of undesirable foreign influences, took root and grew. It was fuelled by deliberately sensational press comments such as “the Bayswater Road [is now] as unsafe as Naples”. Dickens, taking up the theme, had written in an essay of 1860 that the streets of London were as dangerous as the lonely mountains of Abruzzo, drawing on images of isolated Italian brigandage to describe London’s urban environment. The press vied with one another to create comparisons that were intended to alarm the population, from French Revolutionaries to “Indian ‘thuggees’”.

The problem was that most of the fear was manufactured. Not every journal or newspaper entered into the competition to produce sensational copy. Reynold’s Newspaper described it as a load of “fuss and bother” based on “club-house panic”, while The Daily News made cautionary comments about “a social panic”, “wild excited talk” and “exaggerated and fictitious stories”. The newspaper even compared the panic with the venerable old English pantomime tradition and said it appealed to the British sense of humour: “Owing to our peculiar constitutions and our peculiar taste for peculiar jokes, garotting is far from being an unpopular crime.” What with children playing at garotting in the streets, and comic songs being sung about it: “Who can wonder after this that we are problems to our foreign neighbours?”

However, no-one doubted that garotting, though a rare crime, was one with serious consequences for victims. In one case, a jeweller who had fallen into the garotter’s trap when approached by a “respectable looking female” had his throat crushed so badly that he died of his injuries shortly afterwards. The non-fatal but damaging garotting of two notables, one an MP named Pilkington who was attacked and robbed in daylight near the Houses of Parliament, the other an antiquary in his 80s named Edward Hawkins, had helped create the panic. As with all sensational cases, these examples captured the imagination of the public.

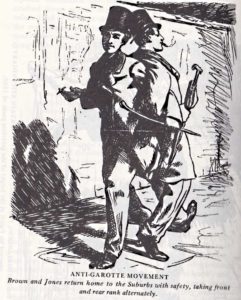

Popular myth suggested that garotters lurked around every corner. Punch produced more cartoons showing wittily ingenious ways in which people might tackle the “crisis”. Some individuals wore Heath Robinson style contraptions; others set out in groups with uniformed escorts and a selection of home-produced weapons. In fact, both these approaches existed in reality, with escorts for hire and defensive (and offensive) gadgets for sale.

The cartoons also served as an attack on both the police, who were believed to be ineffective, and campaigners for prison reform such as Home Secretary Sir George Grey, who was considered to be soft on criminals. The police responded by redefining some minor offences as garotting and treating them with the same severity. In 1863, The Garotter’s Act, which restored flogging for those convicted of violent robbery, was quickly passed.

Though short-lived, the Garotting Panic of the 1860s had lasting consequences. Those who had called for prison reform and the rehabilitation of prisoners were so pilloried in the press, and by Punch in particular, that it had an affect on their campaigns. The critical attitude to the police may have influenced the dismissal of a quarter of the Metropolitan force in the latter half of the 1860s.

Additionally, as a result of the 1863 Garotting Act there had been an increase in actual corporal punishment and death sentences, particularly in regions deemed to foment trouble. In some cases, even innocent men wearing scarves were picked out as potential “garotters”!

Finally, there had also been an increase in vigilante attitudes, as a Punch poem from 1862 shows:

I won’t trust to laws or police, not I,

For their protection is all my eye;

In my own hands I take the law,

And use my own fists to guard my jaw.

Miriam Bibby BA MPhil FSA Scot is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant. She is currently completing her PhD at the University of Glasgow.