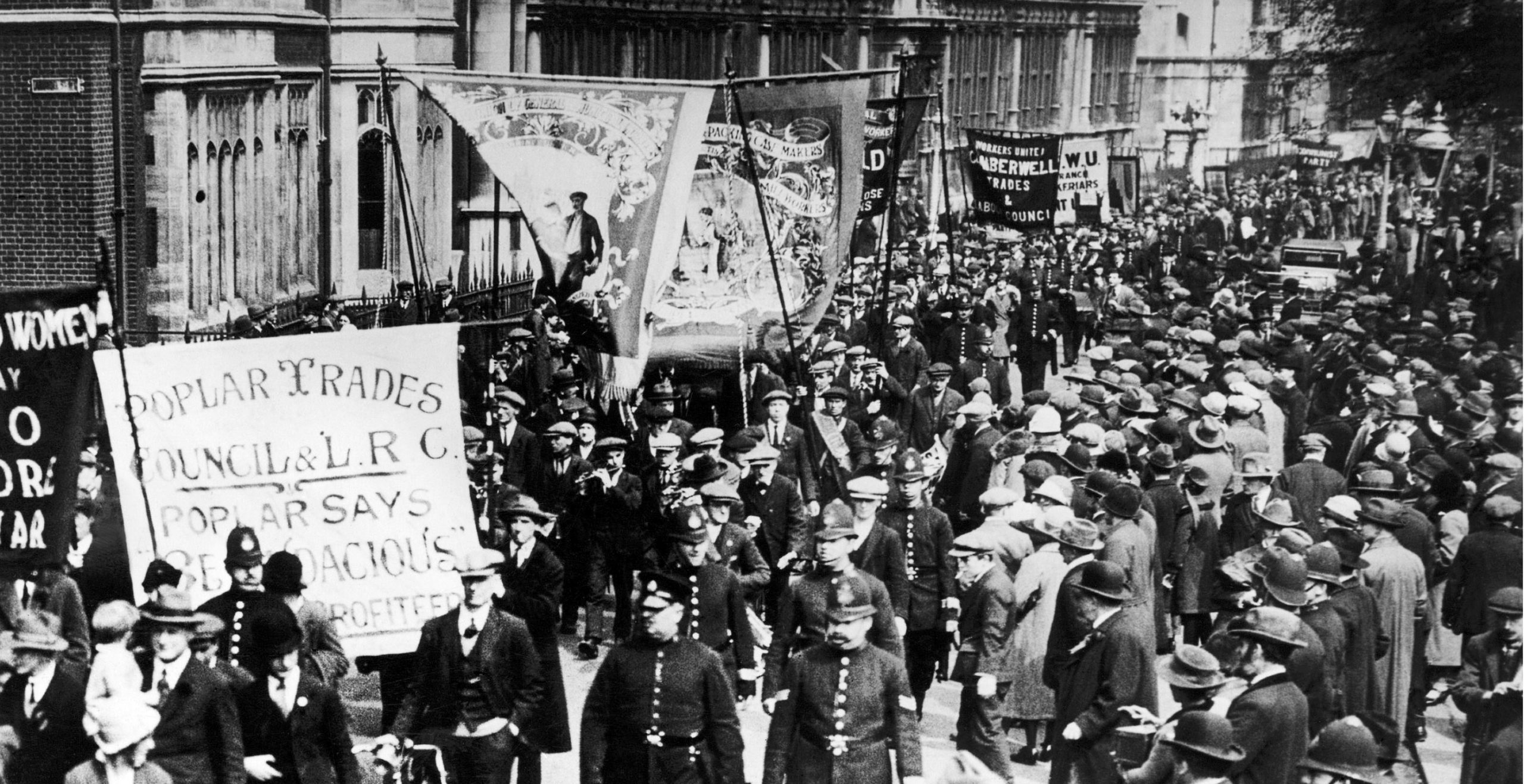

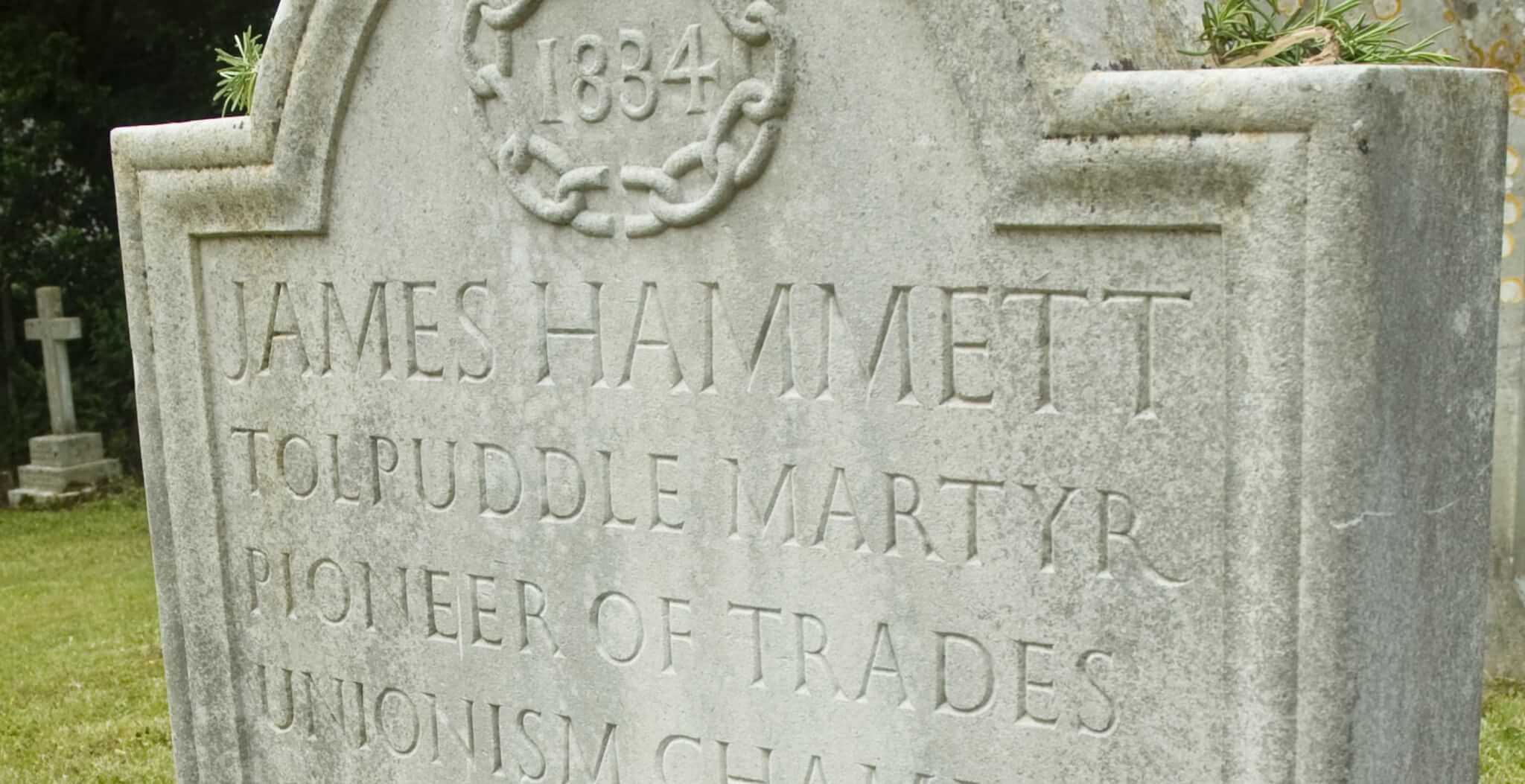

The General Strike, the only one to take place in Britain, was called on 3rd May 1926 and lasted nine days; an historic walkout by British workers representing the dissatisfaction of millions and ushering in the need for change across the country.

On 3rd May 1926, a General Strike was called by the Trade Union Congress in response to the poor working conditions and lessening of pay. This became one of the largest industrial disputes to take place in British history, with millions of people participating in the nine day strike, showing the togetherness and solidarity amongst workers.

There were several reasons contributing to the call for a General Strike. The problems began during the First World War when the high demand for coal lead to a depletion of reserves.

By the end of the war, falling exports and mass unemployment created difficulties throughout the mining industry. This was further impacted by the failure of mine owners to embrace the essential modernisation of the industry as other countries had done such as Poland and Germany. Other countries were mechanising pits in order to increase efficiency: Britain was falling behind.

Furthermore, as the mining industry was not nationalised and was in the hands of private owners, they were able to make decisions such as cutting pay and increasing hours with no repercussions. Miners were suffering: the work was difficult, injury and death was commonplace and the industry was failing to support its workers.

Another factor which worsened the fortunes of the British coal industry was the impact of the 1924 Dawes Plan. This was introduced in order to stabilise the German economy and relieve some of the burdens of wartime reparations, an effective bolster for the German economy which managed to stabilise its currency and re-align itself into the international coal market. Germany began providing “free coal” to French and Italian markets as part of their reparation plans. What this meant for Britain was falling coal prices, impacting negatively on the domestic market.

Whilst coal prices began to fall, they were further impacted by Churchill’s decision to reintroduce the gold standard in 1925. Despite the warnings from the famous economist, John Maynard Keynes, Churchill’s policy was put into practice, a decision that would be remembered as an “historic mistake” by many.

The Gold Standard Act of 1925 effectively had the ill-advised effect of making the British pound too strong against other currencies, adversely affecting the export market in Britain. The strength of the currency needed to be maintained through other processes, such as raising interest rates which in turn proved detrimental for business owners.

The mine owners therefore, feeling threatened by the economic decision-making around them and yet unwilling to concede a declining profit margin, made the decision to cut wages and increase working hours in order to maintain their business outlooks and profit potential.

The miners’ pay in a seven year period was reduced from £6.00 to a miserly £3.90, an unsustainable figure contributing to severe poverty for a generation of workers and their families. When the mine owners announced their intentions to reduce wages further, they were met with fury by the Miners Federation.

“Not a penny off the pay, not a minute on the day”.

This was the phrase which echoed around the mining community. The Trade Union Congress subsequently backed the miners in their plight, whilst in government Stanley Baldwin, the Conservative Prime Minister felt it necessary to provide a subsidy to maintain the wages at their current level.

Meanwhile, a Royal Commission was set up, under the guidance of Sir Herbert Samuel with the intention of investigating the root causes of the mining crisis and thus finding the best possible solution. As part of this commission, the mining industry was investigated for its impact on families, those who were dependent on the coal industry as well as its possible impact on other industries.

The conclusions drawn from the report were published in March 1926 and provided a series of recommendations. Some of these included the reorganisation of the mining industry with the view of making necessary improvements if applicable. Another included the nationalisation of royalties. However, the most dramatic recommendation which would have far-reaching implications was to reduce miner’s wages by 13.5%, and at the same time advising the withdrawal of the government subsidy.

The Samuel Commission was thus accepted by the Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, allowing mine owners to offer their workers new terms of employment with their contracts. This was the beginning of the end for miners who had already been enduring less pay and more work, only to be offered an extension of the working day accompanied by a damning reduction of their wages. The Miners’ Federation refused.

By 1st May all attempts at a final negotiation had failed, leading to the TUC’s announcement of a general strike arranged in defence of the miners’ wages and working hours. This was organised to begin on Monday 3rd May, at one minute to midnight.

Over the next two days tensions built, worsened by tabloid reporting including most notably, a Daily Mail editorial condemning the general strike, labelling the dispute as revolutionary and subversive rather than based on tangible industrial concerns.

As the anger mounted, King George V himself tried to intervene and create a semblance of calm, but to no avail. Matters had now escalated and the government sensing this began to implement measures to deal with the strike. As well as introducing the Emergency Powers Act to maintain supplies, the armed forces, bolstered by volunteers, were used to keep basic services running.

Meanwhile, the TUC chose to limit participation to railwaymen, transport workers, printers and dock workers as well as those in the iron and steel industry, representing other industries which were also in distress.

As soon as the strike began, buses full of blackleg strikebreakers were escorted by police, with troops on guard at bus stations in case any protests got out of hand. By 4th May, the number of strikers had reached 1.5 million, an astounding figure, drawing people from all over the country. The startling numbers overwhelmed the transport system on the first day: even the TUC was shocked by the turnout.

As Prime Minister, Baldwin was becoming increasingly aware of the discontent, particularly with the publication of articles championing the cause of the strikers. Churchill, Chancellor of the Exchequer at the time, felt the need to intervene, saying the TUC had less of a right to publish their arguments than the government. In the British Gazette, Baldwin referred to the strike as “the road to anarchy and ruin”. The war of words had begun.

The government continued to use the newspapers in order to rally support for parliament and reassure the general public that no crisis was being caused by this large-scale walkout. By 7th May, the TUC were meeting up with the commissioner of the previous report on the mining industry, Samuel, in order to bring the dispute to an end. This was unfortunately another dead-end for negotiations.

In the meantime, some men were choosing to return to work, a risky decision as they would face a massive backlash from their striking colleagues, forcing the government to take action to protect them. Meanwhile, the strike rolled on into its fifth, sixth and seventh days. The Flying Scotsman was derailed near Newcastle: many continued to maintain the picket line. The government was managing to maintain a grip on the situation whilst strikers remained defiant.

The turning point came when the general strike was identified as not being protected by the Trade Dispute Act of 1906, except for the coal industry, meaning that the unions became liable for the intention to breach contracts. By 12th May, the TUC General Council met at Downing Street, to announce that the strike was being called off with the agreement that no striker would be victimised for their decision, despite the government stating it had no control over employer’s decisions.

The momentum had been lost, unions faced potential legal action and workers were returning to their place of employment. Some miners continued to resist for as long as November but to no avail.

Many miners faced unemployment for years whilst others had to accept the bad conditions of lower wages and longer working hours. Despite incredible levels of support, the strike had amounted to nothing.

In 1927 the Trade Disputes Act was introduced by Stanley Baldwin, an act which banned any sympathy strikes as well as mass picketing; this act is still in force today. This was the final nail in the coffin for those workers who had taken part in one of the biggest events in industrial history in Britain.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.