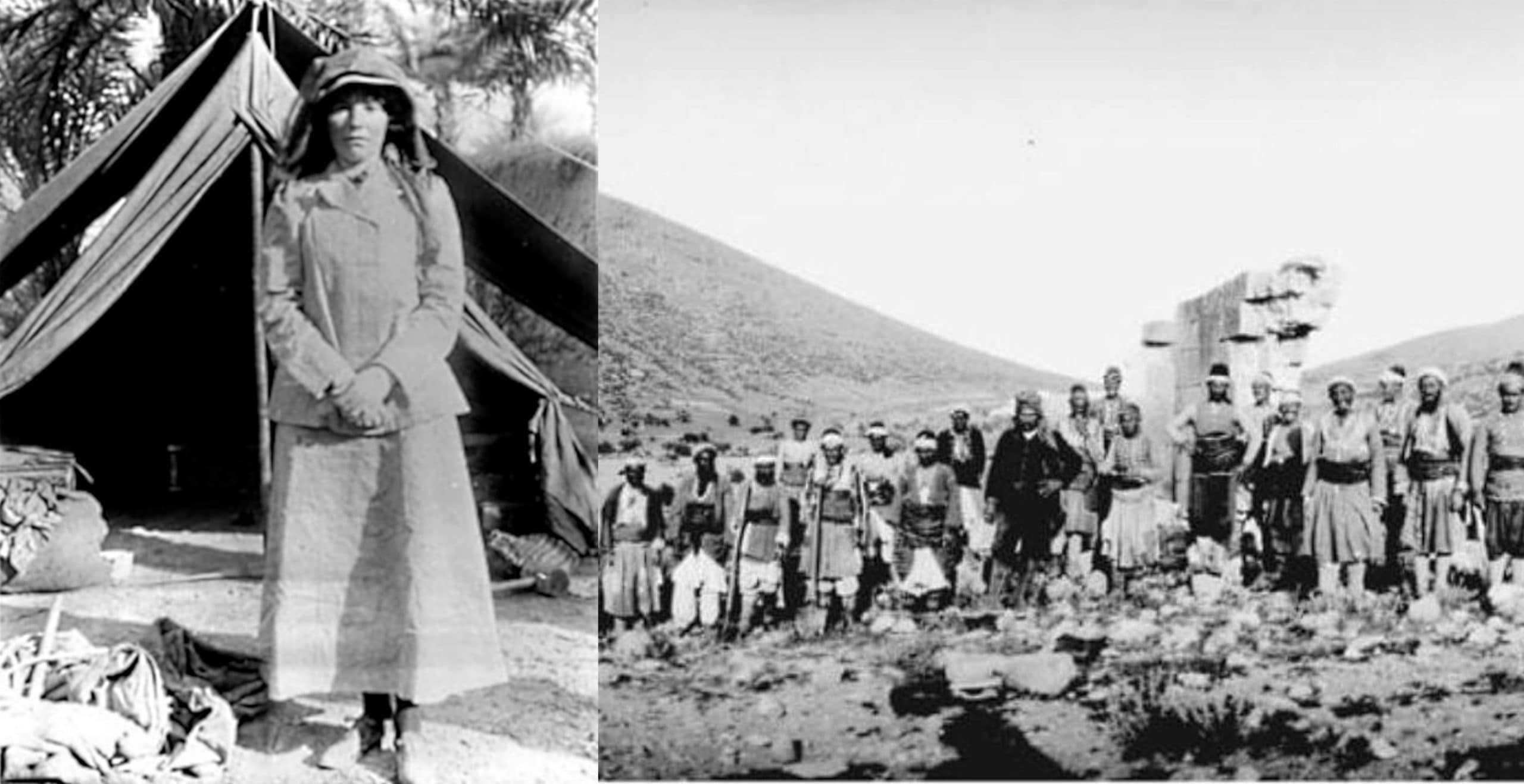

‘Queen of the Desert’ and the female ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ are just some of the names attributed to the intrepid female traveller Getrude Bell. At a time when a woman’s role was still very much in the home, Bell proved what an accomplished woman could achieve.

Gertrude Bell became a crucial figure in the British Empire, a well-known traveller as well as writer, her in-depth knowledge of the Middle East proved to be her making.

Such was the scope of her influence, particularly in modern-day Iraq, that she was known to be “one of the few representatives of His Majesty’s Government remembered by the Arabs with anything resembling affection”. Her knowledge and decisions were trusted by some of the most important British government officials, helping to define a region as well as break new ground as a woman exerting power in the same sphere as her male counterparts.

As a woman seeking to fulfil her own ambitions she benefited enormously from the encouragement and financial backing of her family. She was born in July 1868 at Washington New Hall in County Durham, to a family that was purported to be the sixth richest family in the country.

Whilst she lost her mother at a very young age, her father, Sir Hugh Bell, 2nd Baronet became an important mentor throughout her life. He was a wealthy mill owner whilst her grandfather was the industrialist, Sir Isaac Lowthian Bell, also a Liberal Member of Parliament in the time of Disraeli.

Both men in her life would have an important influence on her as she was exposed to an internationalism and deep intellectual discussions from a young age. Moreover, her stepmother, Florence Bell was said to have had a strong influence on Gertrude’s ideas of social responsibility, something that would feature later in her dealings in modern-day Iraq.

From this grounding and supportive family base, Gertrude went on to receive an esteemed education at Queen’s College in London, followed by Lady Margaret Hall at Oxford to study History. It was here that she first made history as the first female to graduate in Modern History with a first class honours degree, completed in only two years.

Shortly afterwards, Bell began to indulge her passion for travel as she accompanied her uncle, Sir Frank Lascelles who was the British minister in Tehran, Persia. It was this journey which became the focus of her book, “Persian Pictures”, containing a documented account of her travels.

In the following decade she was destined to travel the globe, visiting numerous locations whilst learning a variety of new skills, becoming adept in French, German, Arabic and Persian.

Aside from her linguistic expertise, she also applied her passion for mountaineering, spending several summers scaling the Alps. Her dedication was evident when in 1902 she almost lost her life after treacherous weather conditions left her hanging for 48 hours on a rope. Her pioneering spirit would remain undeterred and she would soon apply her undaunted attitude to new ambitions, this time in the Middle East.

Her tours of the Middle East over the course of the next twelve years, would inspire and educate Bell who would apply her knowledge during the outbreak of World War One.

Intrepid, determined and unafraid to challenge gender roles at the time, Bell embarked on sometimes perilous journeys which were physically demanding as well as potential dangerous. Nevertheless, her appetite for adventure did not quell her passion for fashion and luxury as she was said to travel with candlesticks, a Wedgwood dinner service and fashionable garments for the evening. Despite this love of comfort, her awareness of threats would lead her to conceal guns underneath her dress just in case.

By 1907 she produced one of many publications detailing her observations and experiences of the Middle East entitled, “Syria: the Desert and the Sown”, providing great detail and intrigue about some of the most important locations in the Middle East.

In the same year she turned her attention towards another one of her passions, archaeology, a study which she had grown interested in on a trip to the ancient city of Melos in Greece.

Now a frequent traveller and visitor of the Middle East she accompanied Sir William Ramsay on an excavation of Binbirkilise, a location within the Ottoman Empire known for its Byzantine church ruins.

On another occasion one of her intrepid journeys took her along the Euphrates River, allowing Bell to discover further ruins in Syria, documenting her discoveries with notes and photographs as she went.

Her passion for archaeology took her to the region of Mesopotamia, now part of modern-day Iraq but also parts of Syria and Turkey in Western Asia. It was here that she visited the ruins of Ukhaidir and travelled on to Babylon before returning to Carchemish. In conjunction with her archaeological documentation she consulted with two archaeologists, one of whom was T.E. Lawrence who at the time was an assistant to Reginald Campbell Thompson.

Bell’s report of the fortress of Al-Ukhaidir was the first in-depth observation and documentation regarding the site, which serves as an important example of Abbasid architecture dating back to 775 AD. It was to be a fruitful and valuable excavation uncovering a complex of halls, courtyards and living quarters, all stationed in a defensive position along a crucial ancient trading route.

Her passion and increasing knowledge of history, archaeology and the culture of the region became increasingly evident as her final Arabian trip in 1913 took her 1800 miles across the peninsula, encountering some dangerous and hostile conditions.

With much of her time taken up by travelling, educational pursuits and pastimes she never married or had any children, although she did engage in an affair with a couple of individuals from the British colonial administration, one of whom sadly lost his life during World War One.

Whilst her personal life took a backseat, her passion for the Middle East would serve her in good stead when the ensuing global conflict of World War One necessitated intelligence from people who understood the region and its people.

Bell was the perfect candidate and soon worked her way up through the colonial ranks, breaking new ground as she had done at university, to become the only woman working for the British in the Middle East.

Her credentials were essential for British colonial success, as a woman who could speak several local languages as well as having travelled frequently enough to become accustomed to the tribal differences, local allegiances, power plays and such, her information was invaluable.

So much so, that some of her publications were used in the British army as a kind of guide book for the new soldiers arriving in Basra.

By 1917 she was serving as Chief Political Officer to the British Resident in Baghdad, providing the colonial officials with her local knowledge and expertise.

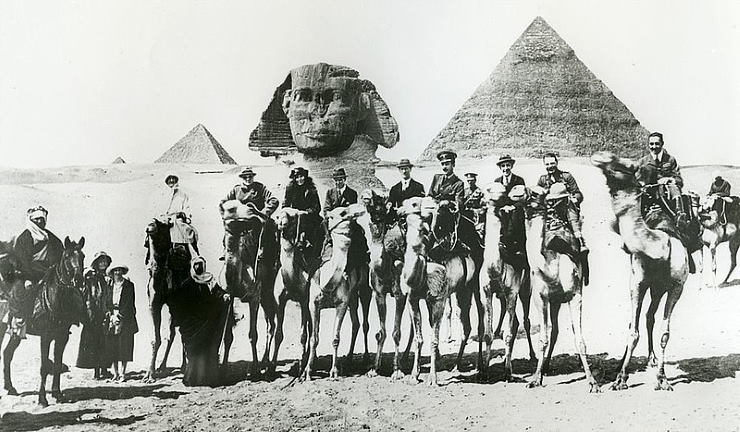

During her time serving the British Army in the Middle East she also encountered T.E Lawrence whilst working in the Arab Bureau in Cairo, gathering intelligence on the Ottoman Empire.

The British attempts to defeat the Ottoman Empire were significantly challenging, suffering numerous defeats, until that was, Lawrence launched his plan to recruit local Arabs in order to propel the Ottomans out of the region. Such a plan was supported and assisted by none other than Gertrude Bell.

Eventually this plan came to fruition and the British bore witness to the defeat of one of the most powerful all-encompassing empires of the last few centuries, the Ottoman Empire.

Whilst the war was over, her influence and interest in the region had not diminished as she took on a new role as Oriental Secretary. This position was that of a mediator between the British and Arabs, leading to her publication, “Self-Determination in Mesopotamia”.

Such knowledge and expertise led to her incorporation into the Peace Conference of 1919 in Paris followed by the Conference of 1921 in Cairo attended by Winston Churchill.

As part of her post-war role, she would prove instrumental in shaping the modern-day country of Iraq, initiating borders as well as installing the future leader, King Faisal in 1922.

Her dedication to the region continued as she was keen to preserve Iraq’s rich cultural heritage and for the rest of her time dedicated herself to such a task.

The new leader, King Faisal, even named Gertrude Bell as the director of antiquities at the new National Museum of Iraq housed in Baghdad. The museum opened in 1923 owing much of its creation, collections and cataloguing to Bell.

Her involvement in the museum was destined to be her last project as she died from an overdose of sleeping pills in Baghdad in July 1926. Such was her impact that King Faisal arranged a military funeral for her and she was laid to rest in the British Civil Cemetery in Baghdad, a fitting tribute to a woman who had dedicated and spent much of her life absorbed in the culture and heritage of the Middle East.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: November 3, 2020.