Nurses in World War One frequently found themselves thrust closer to the frontline than women in previous conflicts. They also led the way in breaking down cultural and racial barriers.

The story of Gertrude Fenn, a nurse from the idyllic countryside of north Essex so vividly captured in the paintings of John Constable, is that of a trailblazer, along with a small group of similarly strong-minded British nurses. They became the first British women to care for Indian soldiers, not on the Western Front but in the searing desert heat of Mesopotamia.

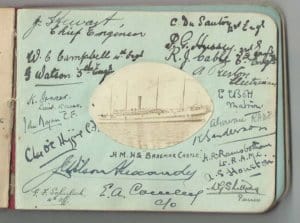

In April 1915, aged 28, Fenn volunteered for war service with the Queen Alexandra Imperial Military Nursing Service (Reserve) and by mid-May was on her way to Malta where the casualties from Gallipoli were pouring in. There she made a positive impact on the men she nursed – probably not difficult for a young female nurse in a predominantly male environment – and she collected many affectionate messages and drawings by British and Australian troops in her autograph books. One written by Sergeant L. Farely of the 3rd Battalion of the Australian Imperial Force on 19 July 1915 is typical of dozens of entries.

“In the lonely spot of Malta

Far from what to me is dear

I find you so kind and lovely

The only one to make me cheer!”

By the spring of 1916 she was serving on the Hospital Ship Braemar Castle, again dealing with casualties from Gallipoli as they were moved from Alexandria to Malta. She was in Alexandria when the call came for QA nurses to volunteer for service in Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq) following fall of Kut.

The capture of Kut by the Turks after a long siege was seen as a catastrophic military failure with the collapse of the medical services in particular viewed as a major scandal.

New commanders were appointed and General Stanley Maude took overall command. One of the first major changes was that all field ambulances and stationary hospitals were combined, ending the inefficient division between British and Indian medical facilities. It wasn’t quite a full integration as British and Indian troops would still be separated within the ambulances and hospitals, but it was a big step forward. They split into sections dedicated to the care of the different nationalities, catering for their different religious, cultural and dietary requirements but with much greater flexibility to allocate medical and nursing resources.

At the start of the campaign, the policy was not to send any women to serve in the fiercely hostile Mesopotamian climate. However, among the medical teams drafted in after the fall of Kut was a 46 year old Irish doctor serving with the Indian Medical Service, Thomas Kelly, who had been caring for Indian soldiers and their families for 20 years. He arrived with a brief to sort out the chaos of thousands of ill and wounded men following the fall of Kut and found hospitals struggling to cope with overflowing wards. He knew the answer lay in going further than just combining British and Indian medical facilities and urged the authorities to send experienced QA nurses to Mesopotamia. The army thought otherwise but Kelly fought General Maude all the way to the High Command and won.

The first nurses arrived in August 1916. Initially they were allocated only to British hospitals, in particular those caring for officers. Their arrival turned a few heads. One Royal Army Medical Corps officer, Campbell Begg described the scene when the first contingent sailed up the Tigris in his post-war memoire ‘Surgery on Trestles’:

“Most of us hadn’t seen a woman – black, white or brown – for the best part of a year. All the British troops who could wangle it converged on the Arab village and took up points of vantage as at a regatta; hundreds lined the banks as the P-boat passed slowly – I was one of them. Cheers resounded along the ranks when the uniforms of the QAIMNS appeared on deck. The sisters were middle-aged and capable-looking; any sex-appeal they had was damped down by their martial dress. But they wore the badge of femininity and they brought with them the aura of homes, and wives and children to the married men; and, to the rest of us, the nostalgic memory of an almost forgotten world which we scarcely hoped to see again.”

Gertrude was among those first women to travel to a country suffering the fiercest heatwaves on record, with temperatures regularly reaching 115°F (46°C). She arrived in Basra and joined the staff at the 3rd British General Hospital at the beginning of August 1916, moving to become Matron-in-Chief at the 40th British General Hospital at Basra in November. Not long after arriving there she suffered a personal reminder of why Mesopotamia was such an unforgiving place to serve when on 1 December, two days before her 30th birthday, she was admitted with a bout of dysentery. She was by no means alone among the nurses in falling ill, as more than half were admitted at some stage during their time in Mesopotamia.

Gertrude Fenn wasn’t going to let this put her off and she was back nursing on the wards just in time for Christmas.

Her patients in Basra thought every bit as highly of her as did those she cared for in Malta. Lance Corporal A. Crisp from the Suffolk Regiment was clearly appreciative of her care:

“In this book I write of Sister Fenn

Who while in hospital on me did attend

Her great kindness and goodness to us,

Will remain dear in our memory from morn till dusk”

She was still at the 40th BGH in Basra when the decision to allow female British nurses to work on Indian wards in the new combined British and Indian hospitals was eventually made in April 1917. She was selected to be among the first six experienced nurses sent to Nasariyah to start the experiment under the leadership of Matron Phoebe Exshaw at the 83rd Combined Stationary Hospital (CSH), one of the new generation of large combined stationary hospitals.

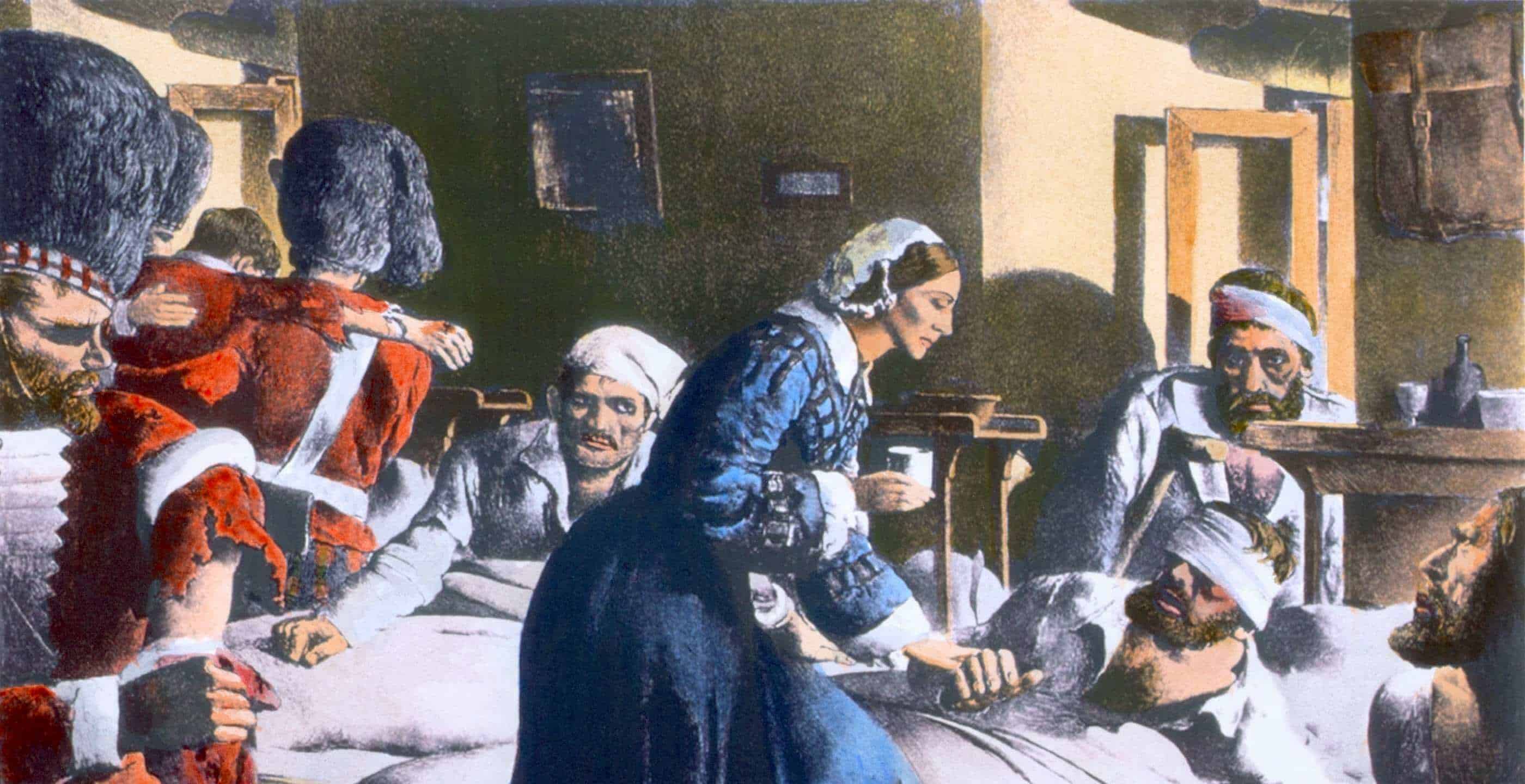

Indian medical units in the field had never had female nurses – they relied on male Indian nursing orderlies – but the Royal Army Medical Corps looking after the British medical units were accustomed to being supported by British nurses, a long tradition made famous back in the middle of the previous century by Florence Nightingale’s exploits during the Crimean War, another conflict where the treatment of the sick and wounded fell far below what was expected.

The 83rd CSH was a 1500 bed hospital with a series of field hospitals and ambulances all the way up the Euphrates to Baghdad and was commanded by the fiercely single-minded Lt. Col. Kelly. He had been battling with his commanding officers again. He wanted the QA nurses to work on the Indian wards too but General Maude was opposed, as he made clear in a memo sent to the War Office in London:

“I agree that theoretically it is desirable that female nurses should look after Indians in Hospital, but practically there are many obstacles. First and foremost the Indian will have to be educated up to the idea of permitting females in a public institution to attend to his needs”.

Just two weeks after that memo was sent, Kelly got his way and in April 1917 the team of six nurses was entrusted to Kelly to prove Maude’s doubts unfounded. The summer had started to gather ominous force as the nurses settled into their hastily arranged and furnished accommodation with just a basic kit consisting of a spare uniform and underclothes, a few possessions and a camp kit that came in a large green bag containing a bed, a canvas bath and basin and a small bucket.

The deployment was a success and the British nurses were accepted on the Indian wards as they quickly became attuned to the sensitivities of the different religions and the caste system.

For Gertrude Fenn there was a personal legacy of her service in the desert.

A year after arriving in Nasariyah, and having not taken any leave for three years, she married Kelly – nearly 20 years older than her – in the Roman Catholic Church of the Holy Name in Bombay (now Bombay Cathedral) on 29 April 1918.

Their two daughters, Brigid and Rosemary were born in India (as it still was before partition), in a hill station at Naini Tal and in Rawalpindi respectively. Rosemary, now 97, is still alive.

When Kelly retired from the IMS in the mid-1920s they settled in Jersey until the outbreak of the Second World War. Her husband, despite being in his 70s, spent that war at sea as a ship’s surgeon in the Merchant Navy while Gertrude used her nursing skills as a volunteer in the shelters at St Martin-in-the-Fields for those made homeless by the Blitz.

She died back in Essex in December 1979, having outlived her husband by 30 years.

All photos courtesy of David Worsfold.

The story of Thomas Kelly’s remarkable life, as well as Gertrude Fenn’s, is told in ‘Fighting for the Empire’ by David Worsfold. ISBN 9781781220061. Hardback, 240 pages. Lavishly illustrated, colour throughout. Available through the publisher Sabrestorm, good bookshops and Amazon.