The last time famine held the people of Paris in its grip, it triggered a series of events which would eventually result in the public execution of the king and the substitution of the French monarchy with the cruel and bloody regime of the Jacobins. In 1794 the leaders of France were once again unable to fill the bellies of the restless Parisians. This proved to be quite a frightening situation as the events leading up to Louis XVI’s execution were still fresh in everyone’s mind.

The hungry masses of the French capital were indeed showing signs of dissatisfaction with their masters as the grain rations grew slimmer and slimmer. This prompted the Robespierre regime to take immediate action: they knew what they were in for if otherwise. The French Committee of Public Safety ordered the local colonial authorities of the French West Indies to collect as much wheat flour as possible from the United States and to ship it across the Atlantic without delay. On 19th April a French convoy of no less than 124 ships under the command of Rear-Admiral Pierre Vanstabel set sail, carrying the precious flour that cost the government one million pounds – an astronomic figure for the time.

.

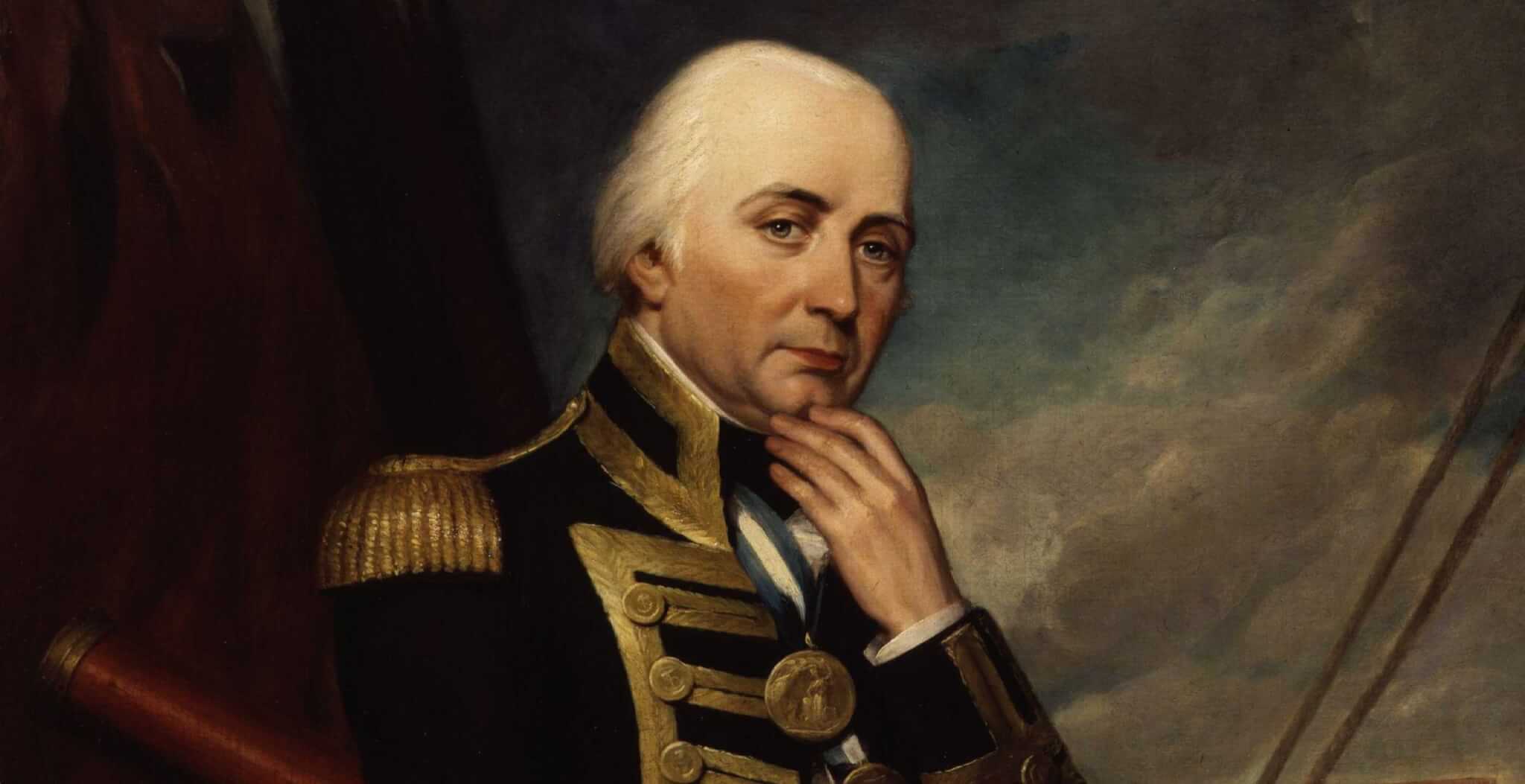

When news of the French transatlantic operation reached England, the Admiralty considered the interception of the convoy as an “object of the most urgent importance”. Indeed, they realised that Robespierre was sitting on a short-fused bomb that certainly would explode if he couldn’t satisfy his “Citoyens” with food at short notice. Realizing this opportunity, they ordered the admiral of the Channel Fleet, Richard Howe, to intercept Vanstabel’s ships. He set course for Ushant in order to observe the movements of the French main battle fleet at Brest and at the same time sent Rear-Admiral George Montagu forward into the Atlantic with a sizeable squadron to search for and apprehend the grain convoy.

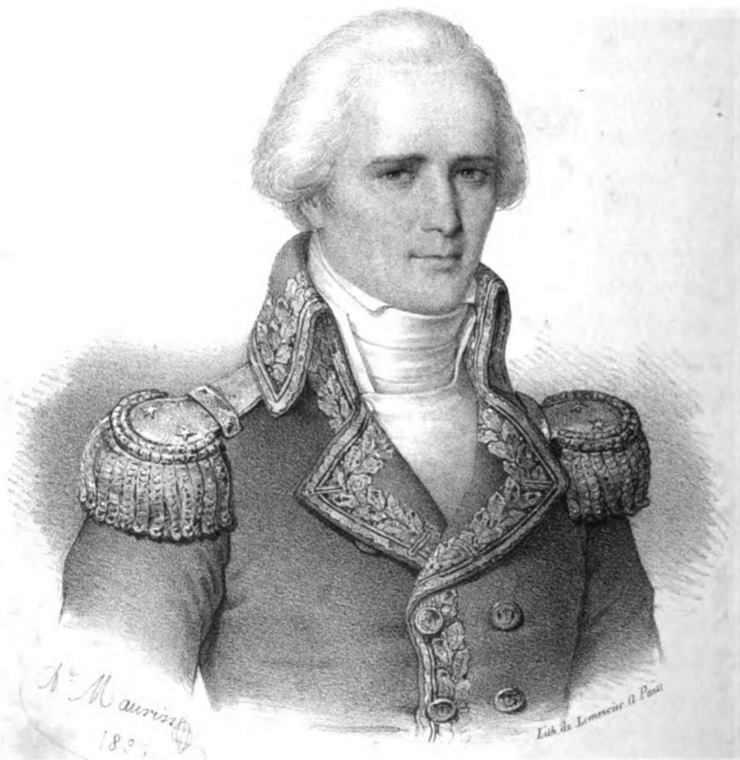

Meanwhile behind the confines of the port of Brest, Admiral Louis Thomas Villaret de Joyeuse was preparing for his part in the “wheat” operation. The French Committee of Public Safety had appointed the commander of the Brest fleet with the vital task of protecting the grain ships. They made it quite clear to Villaret de Joyeuse to do his utmost to thwart any British attempt to take Vanstabel’s ships. During the dark, foggy night of the 16th to the 17th of May, Villaret de Joyeuse managed to slip past Howe’s fleet into the Atlantic. As soon as the Royal Navy’s commander was made aware of the French escape, he set in for the pursuit. His plan was clear: the main British battle fleet was to deal with Villaret de Joyeuse, while Montagu was to capture the convoy.

On 28th May at 6:30 AM the reconnoitering frigates of the Royal Navy eventually caught sight of the French fleet 429 miles west of Ushant. What followed was a series of small brushes between the opposing sides. While Villaret de Joyeuse was focusing himself on luring Howe away from the convoy, his British colleague danced around the French fleet in order to gain the weather gauge. Having the weather gauge meant that Howe would be upwind of the French.

This position would make him benefit of an approach towards the enemy with obviously more speed, more steerageway and thus more initiative than his opponent. Both succeeded in their intentions. Villaret de Joyeuse’s diverting manoeuvres had put a sizeable distance between the Royal Navy and Vanstabel’s ships. Lord Howe on the other hand had positioned himself windward of the French line on 29th of May, thus gaining the initiative. Two days of dense fog hindered the Royal Navy from taking any further action while the two fleets sailed parallel on a north-westerly course.

At 07:26 on the morning of 1st June, as the sun at last broke through and routed the hazy weather, Howe ordered his ships to clear the decks for action. His plan was for each of his vessels to bear down on Villaret de Joyeuse’s fleet individually and to force a passage through the French line wherever possible, wreaking havoc with devastating broadsides into the enemy sterns and bows during their passage to the other side of the Republic’s fleet.

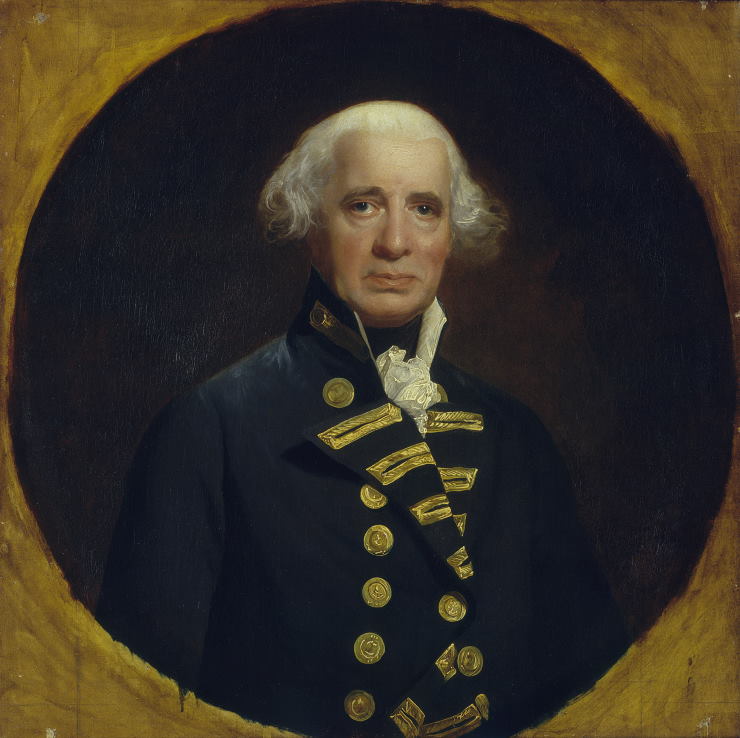

He envisioned his men-o’-war to subsequently reform to leeward of Villaret de Joyeuse’s ships in order to cut off their escape route. For the greater part Howe had based his tactics on those of Admiral Sir George Rodney (1718-1792) at the Battle of the Saintes (1782). In theory, this was such a brilliant manoeuvre that Lord Adam Duncan (1731-1804) would later re-use this stratagem at the Battle of Camperdown (1797).

Many of Howe’s captains, however, failed to apprehend the admiral’s intention. Only seven of the twenty-five British battleships managed to cut through the French line. The majority on the other hand weren’t able or did not bother to pass through the enemy and engaged to windward instead. Consequently, after the victory, a wave of inquests swept through the fleet with several officers, such as Captain Molloy of HMS Caesar, being dismissed from command due to neglect of the admiral’s orders. The British nevertheless bested their opponents thanks to their superior seamanship and gunnery.

The first shots were fired at around 09:24 and the battle soon developed into a series of individual duels. One of the most notable actions was the intense exchange of fire between HMS Brunswick (74) and the French ships Vengeur du Peuple (74) and Achille (74). The British ship was so closely hauled to her opponents that she had to close her gunports and fire through them. The Brunswick would suffer heavy damage during the onslaught. There were in all 158 casualties aboard this third-rater, amongst whom the much-revered captain John Harvey (1740-1794) who would later succumb to his wounds. The Vengeur du Peuple on the other hand became so badly damaged that she sank shortly after the engagement. The sinking of this ship would later become a popular motive in French propaganda, symbolising the heroism and self-sacrifice of the Republic’s sailors.

The Glorious First of June was swift and fierce. Most of the fighting had ceased by 11:30. In the end, the Royal Navy managed to capture six French ships with another one, the Vengeur du Peuple, being sunk by the devastating broadsides of the Brunswick. In total, around 4,200 French sailors lost their lives and a further 3,300 were captured. This made the Glorious First of June one of the bloodiest naval engagements of the eighteenth century.

The butcher’s bill of the French fleet was perhaps one of the most catastrophic consequences of the battle for the Republic. Recent studies have shown that on that fateful day Britain’s nemesis had lost about 10% of her able seamen. The manning of warships with experienced crew members would indeed prove to be a major issue for the French navy for the remainder of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. The British casualty rate was also relatively high with about 1,200 men killed or wounded.

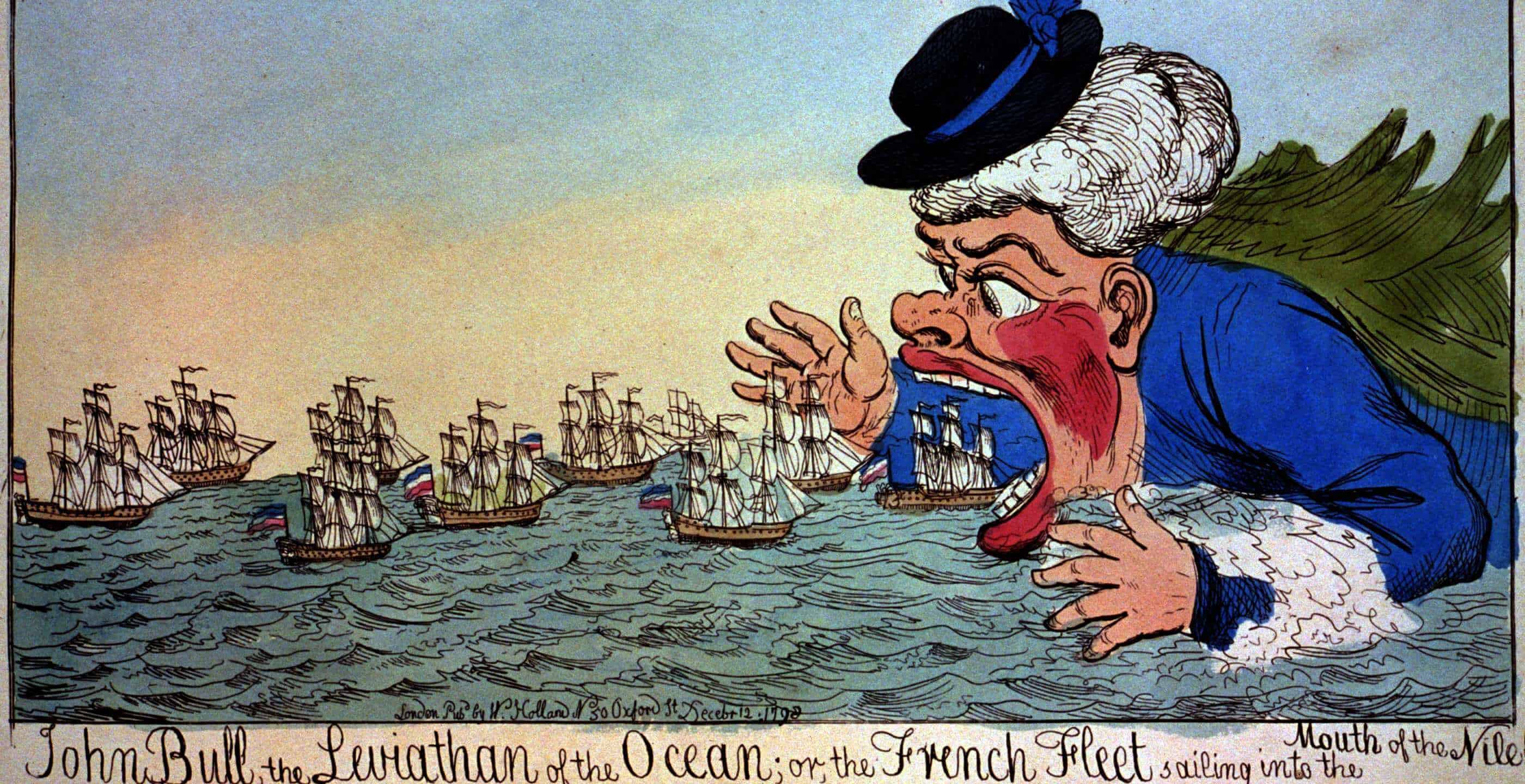

When word reached Britain, there was a general rejoicement among the populace. It was claimed as a glorious victory, regardless of the escape of the convoy, which Montagu’s squadron had failed to apprehend. The British however had good reason in perceiving Howe’s engagement with Villaret de Joyeuse in such a way. In terms of numbers, the Glorious First of June was one of the Royal Navy’s biggest victories of the eighteenth century. Howe instantly became a national hero, being honoured by King George III himself who later visited the admiral on his flagship, HMS Queen Charlotte, in order to present him a bejewelled sword.

Meanwhile in Paris the Robespierre regime was doing its utmost to emphasize the strategical success of the campaign, pointing out that the wheat flour had safely arrived in France. It proved to be quite difficult however to present such a crushing tactical defeat as a triumph. The loss of seven ships of the line must have felt as an embarrassment which in turn further undermined the already low credence of the current government. One month later Maximilien de Robespierre would end up on his favourite instrument of power, the guillotine. Thus ended the Reign of Terror while Britain proudly relished its moment of glory.

Olivier Goossens is currently a bachelor student of Latin and Greek at the Catholic University of Louvain. He has recently obtained his master degree in ancient history at the same university. He researches the hellenistic history of Asia and hellenistic kingship. His other major field of interest is British naval history.

Published: 18th January 2022.