Mention the phrase “The Great Train Robbery” and most people will immediately think of the events of 1963, when a group of robbers held up the Glasgow to London mail train. The most notorious member of the gang, Ronnie Biggs, escaped from prison and fled to Australia and South America before giving himself up in 2001.

The Great Train Robbery is still viewed as audaciously well-planned and executed but it was not unique. Nearly a century earlier, another Great Train Robbery, also known as the Great Gold Robbery, took place on the London to Folkestone section of the route of a train carrying a large quantity of gold bullion.

Transporting and securing wealth had always created problems for those who owned it. Gold, that most precious of gleaming metals, had its own unique allure for the elite and the avaricious, as revealed in numerous legends of buried treasure and the folk tales of Robin Hood. The regular discovery of hidden hoards and the continuing popularity of daring heists shows that the legends have a core of truth. In the mid-nineteenth century, large quantities of gold bullion still needed to be transported between cities, and the use of railways facilitated these transfers as never before.

There was nothing unusual on the evening of 15 May 1855 about transferring three secure boxes from London to Paris that contained gold to the value of £12,000 in coin and bars. The total weight in gold was 224 pounds (102 kg). This weight in gold would be valued at a phenomenal £6,732,000 at October 2024 rates! The gold was carried on the regular South Eastern Railway (SER) mail train service that left London Bridge daily at 8.30 pm for Folkestone, one of three scheduled mail train journeys each day.

Of course, every precaution had been taken to ensure the safe conveyance of the gold. It was carried in wooden boxes that were tightly bound with iron bands and sealed with wax. The seals were those of the bullion dealers Abell & Co, Messrs Bult & Co, and Adam Spielmann & Co. The cases were picked up and transferred to London Bridge by Chaplin & Co. The carriers had weighed and sealed the boxes themselves.

Once they had arrived at the station, the boxes were locked inside dedicated iron travelling safes made by the famous Chubb & Son. These were solid affairs constructed from steel 1” (2.5cm) thick. Each safe had two sets of locks, both identical pairs. Only certain approved railway staff and the captain of the night steamer had access to the keys, no one individual had access to both keys, and the safes were under the care of the guard of the Folkestone night service and the captain of the Boulogne ferry for the duration of the journey. What, as they say, could possibly go wrong?

The safes were collected, as usual, by French counterparts at Boulogne, the Messageries impériales, who were responsible for their train journey to the Gare du Nord and their carriage to the resting place in the vaults of the Banque de France. When they arrived, the boxes were weighed as usual, only to find a major discrepancy in two of them.

The boxes were opened in Paris, and we can only imagine the shock and cries of “Hélas!” “Mais c’est impossible!” when the bank officials discovered the bound and secure wooden boxes were filled not with gold but lead shot! It was a trick worthy of a stage magician, or possibly the world’s least successful alchemist – that of turning gold into lead.”

The English authorities insisted the robbery must have taken place in France; the French authorities refuted it. Somehow, in some manner, the still locked safes had been accessed, the still sealed and bound boxes had been emptied of their gold and lead shot put in to replace it. How on earth was it possible?

A spectacular heist like this had clearly taken a great deal of planning and for nearly eighteen months the authorities on both sides of the Channel investigated the crime without success. There must have been suspicions that it was an inside job, and that was the case. A former employee of the SER, William Pierce, had proposed the crime. Fond of gambling, boozing, and loud suits, Pierce had lost his job with the SER because of his betting and drinking.

One of Pierce’s drinking companions was a burglar and skilled safe-cracker known as Edward Agar. He had made a successful career as a criminal and provided the skills, while Pierce provided insider knowledge and contacts. One of the essential skills of the professional safe-cracker was being a screwsman, as historian Kellow Chesney points out. This was a skeleton key expert.

Blowing safes up with dynamite may make for sensational media coverage, but there were far subtler ways to acquire the gold, as Agar knew. How to acquire the keys was the next and most complex part of the robbery.

It was essential to bring in confederates with access to the safes. One was train guard James Burgess, long-time employee on the SER Folkestone line. No one would suspect the respectable Burgess, but he had found his own income from the company reduced due to hard times and so had a grievance.

Clerk William Tester was in a key role at London Bridge station as assistant to the superintendent. He provided inside information about the movement of the gold and the times that Burgess would be the train guard on the Folkestone train. One more character would play a part in the robbery and its aftermath. That was Fanny Kay, former railway employee and Agar’s partner.

Tester took advantage of some repairs being done to the safes to acquire the keys briefly and take wax imprints. In his anxiety he made the mistake of duplicating just one key, twice! Agar and Pierce managed to get an imprint of the second key later while the office staff were distracted elsewhere. Agar also managed a dummy run with some gold acquired with his own wealth to gain further insight into how gold transfers were managed.

Agar and Pierce stocked up with lead shot to be carried in bags and prepared for the night when Burgess would be on the rota as guard for the trip. They boarded the train and Agar hid himself, while Pierce remained in one of the compartments and watched.

Before the train reached Redhill, Agar had applied his skills to successfully empty one safe and box of its gold bars and replace it with the shot. The gold was handed to Tester at Redhill, who returned to the SER offices and provided himself with an alibi.

Only one of the keys had been needed, since only one lock had been locked, rather than both. Agar drew out the rivets from the iron bands round the boxes and nailed them back after the gold had been removed and replaced by the lead shot. The broken seals of the bullion dealers had been replaced with seals that would pass a cursory glance in dim light. To all intents and purposes, nothing had changed between London and Paris, and damage to the boxes noted on their arrival in France was presumed to have existed from the start of their journey.

The other two boxes, containing American Gold Eagle coins and more gold bars, were emptied and shot placed in them before Folkstone. The weights did not match as the conspirators did not have enough shot, so Pierce and Agar left some gold bars behind. They left the train at Dover, no doubt looking like bulky passengers with gold-stuffed courier bags under their coats, and hefting weighty gold-crammed Gladstone bags. Exchanging the American gold coins, and melting down the gold bars, they prepared to enjoy the fruits of their crime.

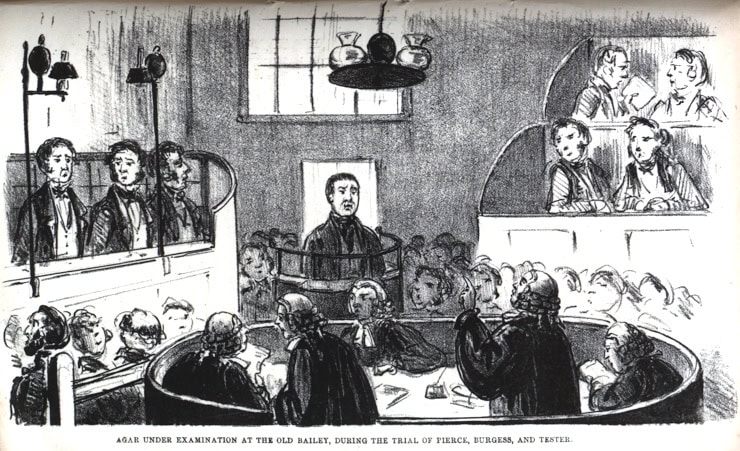

Despite the offer of a reward of £300, they would have got away with it too, if it hadn’t been for Agar falling foul of the law for something else. As was so often the case, it was lack of honour among thieves that led to the downfall and arrest of members of the gang. Edward Agar was accused of the crime of forgery for another incident, although he may have been innocent. Confined to jail, he asked Pierce to give some of his loot to Fanny Kay, the mother of his child, whom he’d left for another woman. Pierce didn’t do this.

Understandably annoyed, Fanny Kay spilled the beans to the Newgate prison governor, naming Pierce, Burgess, and Tester as accomplices. Edward Agar, in Pentonville Prison under threat of transportation to Australia, corroborated her story. Burgess, Tester and Agar “got the boat”, in other words were sentenced to transportation, but did not serve their full term. Pierce served two years hard labour in England.

The story of the Great Gold Robbery of 1855 provided the theme for a novel by Michael Crichton in the 1970s (“The Great Train Robbery”) and a farcical comedy film (“The First Great Train Robbery”) based on Crichton’s book. A starry cast including Sean Connery, Donald Sutherland and Lesley-Anne Down acted out the story what remains one of the most audacious robberies ever committed.

Dr Miriam Bibby FSA Scot FRHistS is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published: 12th February 2025