On 5 February 1811, George, Prince of Wales, was declared Regent of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The new Prince Regent had been waiting for this moment for a very long time. Over the years his father, King George III, had suffered several bouts of a mystery illness that had amounted to insanity, but had always recovered before a regency had become necessary. By late 1810, however, the King appeared to be more or less permanently incapacitated. A few months later, the Prince was authorised to rule in his stead.

One of George’s first acts as Regent was to throw a grand party. Two thousand people, all members of Britain’s high society, were invited to an evening fête on 19 June at Carlton House, the Regent’s palatial home on Pall Mall. It was announced that the party was being held for two reasons: firstly to mark the King’s birthday, which fell on 4 June, and secondly to honour those members of the French royal family who were living in England after fleeing Revolutionary France.

By nine o’ clock that warm summer evening, the lines of coaches pulling up outside Carlton House stretched down Pall Mall and St James, blocking the roads as far as Bond Street. The guests were dressed in their finest clothes – the Regent had asked them to wear articles of British manufacture, which no doubt pleased the London modistes and tailors. Some of the guests had also given their support to the local pawnbrokers, who were lending out diamonds for the occasion at eleven per cent interest.

The Regent was dressed to impress in a gorgeous field-marshal’s uniform of his own design and carried a gilded and jewelled sword. His tunic of red velvet, heavily embroidered with gold, was decorated with the Order of the Garter and a glittering diamond-encrusted star. He greeted the guests of honour, who included the Comte de Lille and the Comte D’Artois, the future Kings Louis XVIII and Charles X respectively, in a room hung with silk panels displaying the Bourbon fleur-de-lis.

According to newspaper reports, the guests included ninety-eight earls, thirty-nine viscounts, a hundred and seven lords, and too many barons, counts, admirals and generals to be counted. There were some notable absentees among the glittering crowd, however. These included the Prince’s estranged wife, Princess Caroline, and his mother, Queen Charlotte. Caroline had not been invited, but the Queen had refused the invitation, and had forbidden her five daughters to attend. Charlotte was well aware that whatever the ostensible reasons for the fête, it was in reality a grand celebration of her son’s accession to power – a display of public rejoicing that might well be considered inappropriate, given his father’s condition.

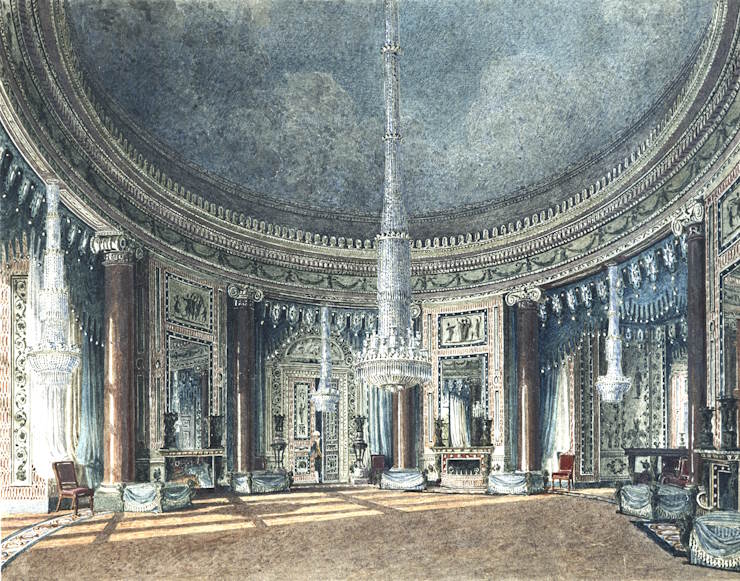

This display of family disapproval did not deter the Prince, who intended to make it a night to remember. The guests entered Carlton House through the Grand Grecian Hall, accompanied by music from military bands. A phalanx of Yeomen of the Guard in their distinctive costumes lined the route through the richly decorated Octagon Saloon and out into the gardens, which were illuminated by thousands of shimmering lights and filled with flowers, ornamental shrubs and miniature fruit trees.

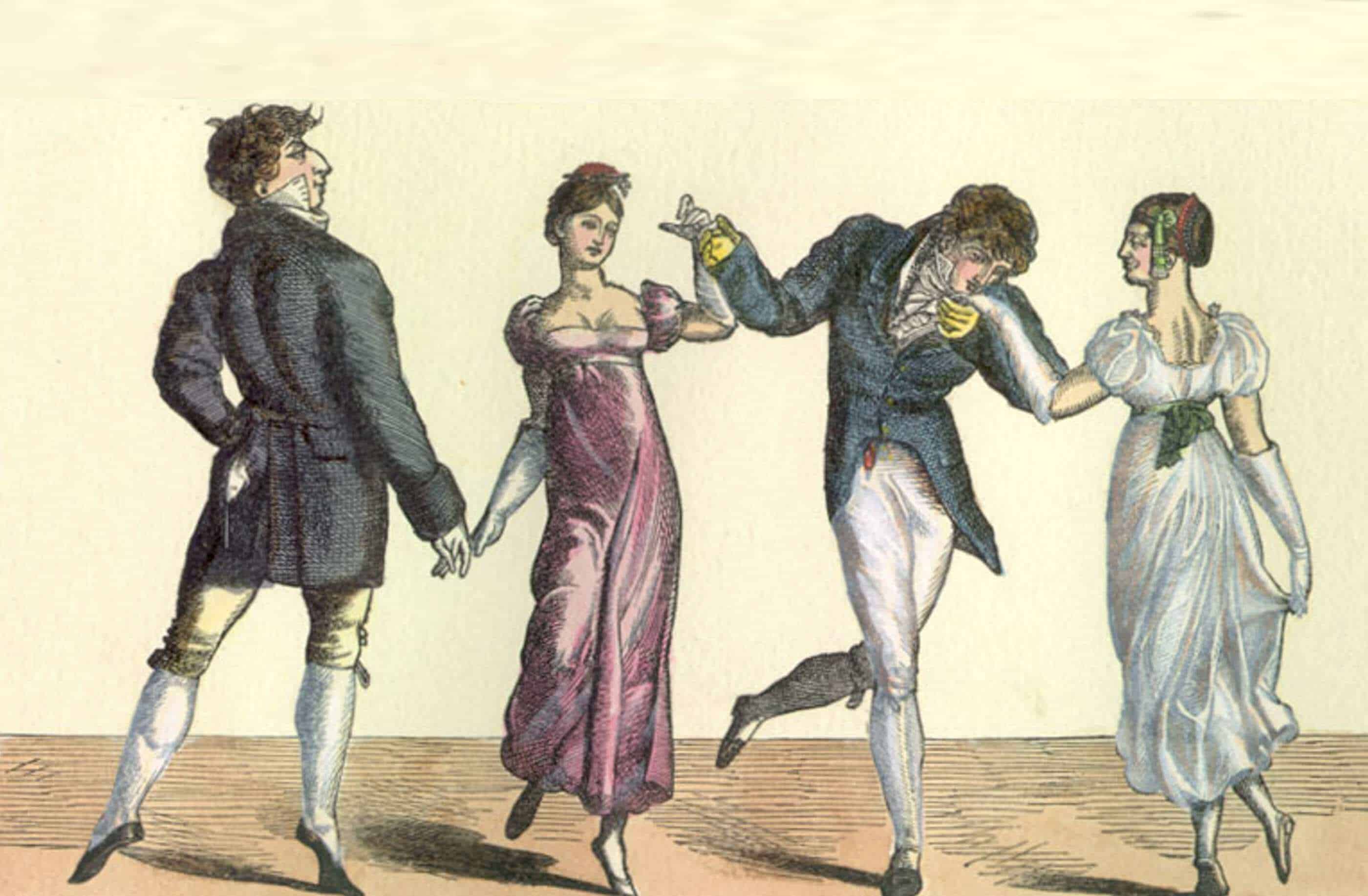

Dancing began at midnight in the ballroom, where Earl Percy and Lady Jane Montague led off the first dance. After a fireworks display, the meal was served at two thirty in the morning. It consisted of all ‘the delicacies of the season’, including iced champagne, fine wines, roasted meats and exotic fruits. As befitted a royal gourmet, the Prince employed some of the best cooks in Europe. The Regent’s head chef, Jean-Baptiste Watier, supervised the preparation of the food for the fête; the desserts were provided by the Duchess of Dorset’s confectioner, an expert in his field, who had been loaned for the occasion.

A special top table was laid inside the Gothic Conservatory for a hundred and forty of the Prince’s closest friends. The majority of the guests sat in adjoining rooms and in marquees in the gardens. The Prince’s table, which was nearly two hundred feet long, ran the entire length of the conservatory. He sat at the head of it on a crimson velvet throne edged with gold.

The guests at this VIP table were served by sixty servants, including one man in a full suit of medieval armour. The diners ate off a magnificent gold dinner service, made by the royal goldsmiths, Rundell, Bridge and Rundell. It had been a lucrative commission for the firm, as the whole service, which had been created over several years and made its first appearance at the fête, had cost over £60,000. It became known as the ‘Grand Service’ and is still used for state occasions.

At the top end of the table, where the Prince sat, a miniature fountain ran into a silver-lined channel, forming a river which flowed down the length of the table. Live goldfish swam in the little stream, which was edged with banks made of mosses and flowers. Sadly, few of the fish survived the evening. According to one report, ‘at the height of their honours and glory, the greatest any of their kind had ever attained before, they were seen, with astonishment and dismay, to turn on their backs, the one after the other, and to expire’.

The fête, which was rumoured to have cost a mind-blowing £120,000, continued into the early morning, the last guests leaving at six o’ clock. This elaborate and lavish party had an unfortunate postscript, however. The Regent decided to open Carlton House over the following three days, to allow the public to view the scene of the great event.

The open days were advertised as ‘by ticket only’, but thousands of curious sightseers flocked to Pall Mall. On the last day, a crowd of around thirty thousand tried to gain entry. The Prince’s naval brother, the Duke of Clarence, clambered onto the garden wall in an attempt to control the situation, but chaos ensued, ending in a wild stampede in which some visitors were trampled and injured, a number of women lost their shoes, and others had their gowns ripped from their bodies. The next day, a large tub of shoes was placed outside Carlton House, for people to reclaim their lost property.

The newspapers described the fête as an evening ‘no less brilliant than one of those so glowingly described in the Arabian Nights’, but not everyone was impressed by this display of magnificence. The British economy was suffering from wartime inflation and high unemployment, and the Prince Regent’s profligacy was seen in sharp contrast to the widespread poverty among the lower classes.

The lawyer and politician Sir Samuel Romilly, who had been a guest at the party, had remarked on the inappropriateness of the lavish splendour of the event in the face of ’the misery of the starving weavers’. Shortly before the fête had taken place, the distressed weavers of the north-west of England had submitted a petition to the House of Commons begging for help. The Prince may have had this in mind when asking his guests to wear British clothing, but the gesture was a mere drop in the ocean.

The extravagance of the Regency fête epitomised the Prince’s life-long love of excess. He ate and drank recklessly: it was not unusual for him to drink three bottles of wine at dinner, then continue throughout the evening with stronger drinks, such as punch and cherry brandy.

He did not moderate his habits after he inherited the throne as George IV in 1820. A few years later the Duke of Wellington noted that the King ‘drinks spirits morning, noon and night … and he is obliged to take laudanum to calm the irritation which the use of spirits occasions’. The main constituent of laudanum, a widely used medication, was opium, and it was highly addictive. George IV died in 1830 at the age of sixty-seven, his health ruined by his over-indulgence.

Elaine Thornton is a writer of articles on British history and the author of a biography of the opera composer Giacomo Meyerbeer, Giacomo Meyerbeer and his Family: Between Two Worlds (Vallentine Mitchell. 2021).

Published: 17th May 2024