“Can you see anything?”

“Yes, wonderful things!”

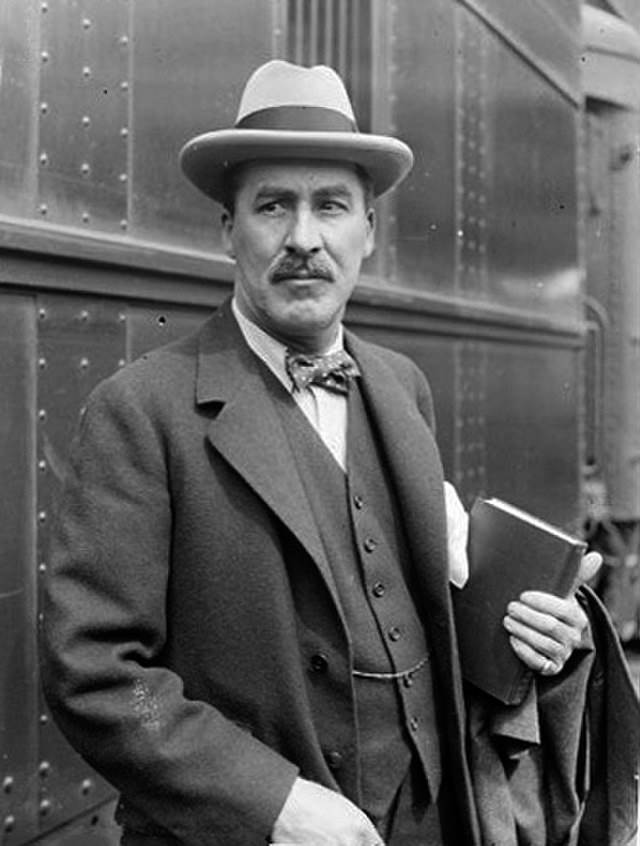

These are the famous words of Howard Carter at the moment when he discovered Tutankhamun’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings.

On 26th November 1922, the British archaeologist and Egyptologist Howard Carter, holding a candle in one hand, made a tiny hole in the doorway of a tomb. Taking his first look, he peered through a small crevice, revealing for the first time, the contents of Tutankhamun’s tomb.

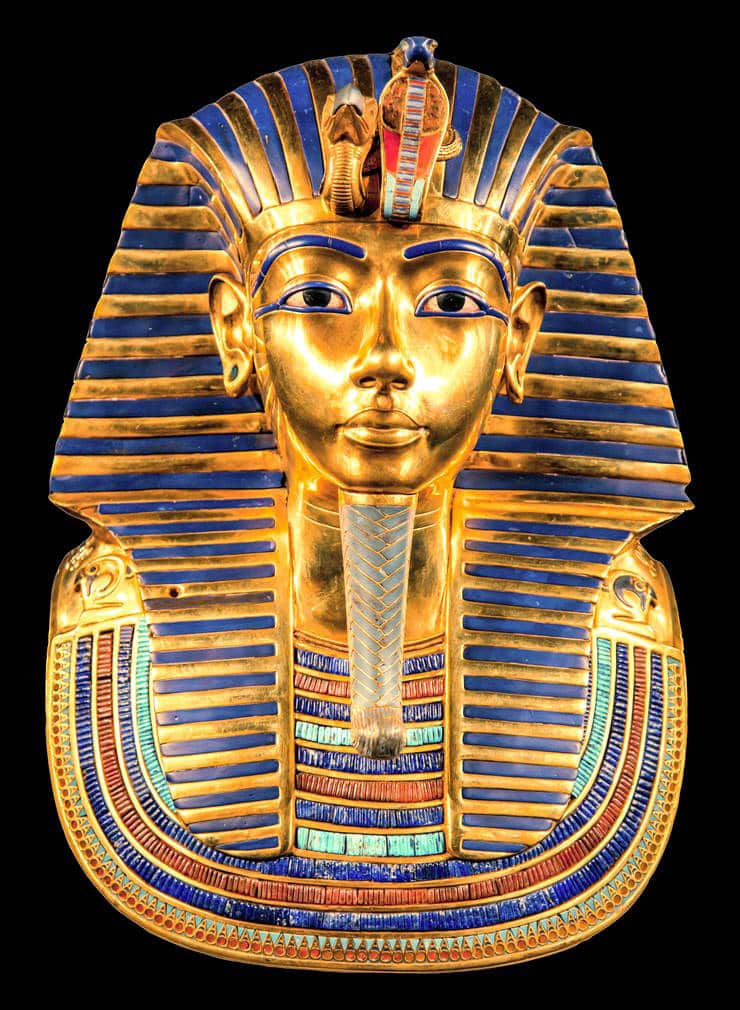

This was an outstanding and legendary discovery that garnered attention from around the world. The discovery of an intact tomb belonging to the 18th Dynasty Pharaoh, the “boy king” Tutankhamun himself, was a breath-taking moment.

In the decade that followed, Carter and his team would methodically excavate the contents, which included the pharaoh’s mummified body as well as wall paintings, religious objects and equipment accompanying the king into the afterlife.

Howard Carter, the archaeologist who made this monumental discovery, was born in Kensington, the son of an artist called Samuel Carter. In his youth he experienced poor health which led to him being sent away from the hustle and bustle of London to Norfolk, to live with extended family and be privately schooled at home.

As a young boy he benefited from living near Didlington Hall, a mansion in the area belonging to the Amherst family. Within the home was an impressive collection of Egyptian artefacts which sparked a life-long interest in the subject in young Carter.

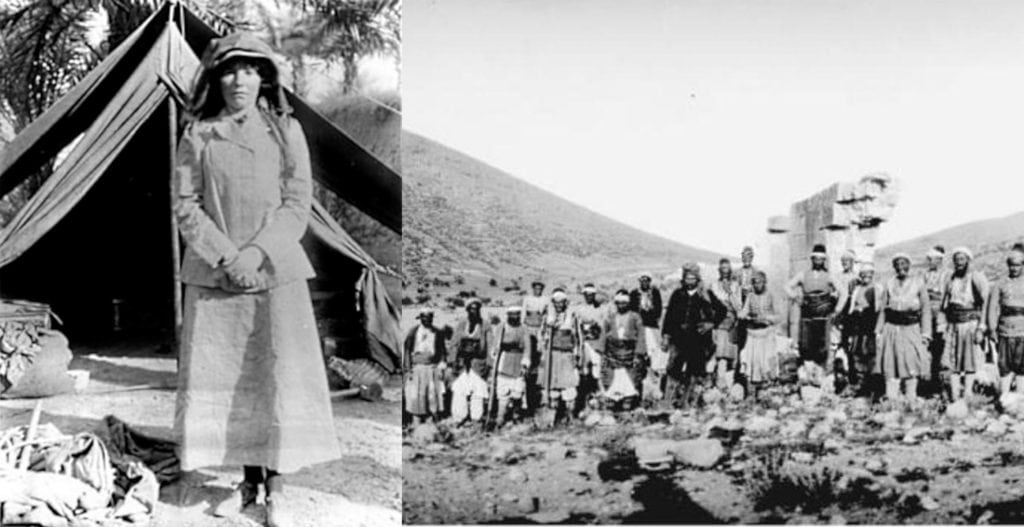

With the help of his father, Howard Carter developed the skills required for Egyptology. With the assistance of the Egypt Exploration Fund, in 1891 he was invited to join Percy Newberry in an excavation of the tombs at Beni Hasan.

The Egypt Exploration Fund is a society founded in 1882 to study and excavate predominantly in Egypt as well as Sudan. As part of their work, numerous archaeological discoveries have been made including the model of Nefertiti from Amarna.

The young Carter would benefit from these important connections. He would go on to learn and work under the leadership and guidance of the esteemed Flinders Petrie in Amarna as well as Henri Édouard Naville, with whom he joined an excavation at the temple of Hatshepsut.

As he continued to hone his craft and learn from the best, in 1899 he was offered a prominent position as Chief Inspector of the Egyptian Antiquities Service. Now in this new job, Carter took a leading role in supervising a number of excavations including that at Thebes.

In 1905, Carter incurred difficulties when a confrontation broke out between Egyptian guards and French tourists. The disruption occurred at Saqqara, a burial site for the Ancient Egyptian capital of Memphis.

Carter evaluated the situation and sided with the Egyptian guards, however this altercation soon escalated and led to an inquiry known by many as the Saqqara Affair. Following this dispute he chose to resign from his position.

However all was not lost for the rising star of archaeology; only two years later, he was introduced to Lord Carnarvon.

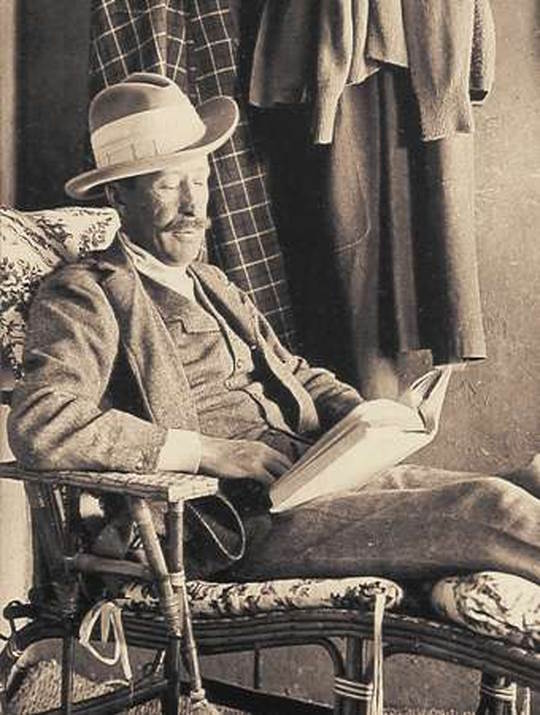

Lord Carnarvon was an English aristocrat and peer by the name of George Edward Stanhope Molyneux Herbert, who inherited the imposing and magnificent Highclere Castle (well-known as the setting for Downton Abbey). He would become famous however for his fiscal support which allowed Carter to discover Tutankhamun’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings.

An enthusiast for Egyptology, he employed Carter’s expertise and provided the necessary financial backing to search for Tutankhamun’s tomb. Based on a recommendation, Carnarvon felt that Carter possessed the necessary modern methods and techniques to apply to the many excavation projects which he financed. In 1907 the partnership began, with Carter employed as the principal supervisor for all of Lord Carnarvon’s excavations.

In 1914, the outbreak of the First World War halted proceedings, with Carter spending the wartime years working in the diplomatic service. During this time, he was both a courier and translator, however at the end of 1917 he was finally able to resume his usual activities.

For several years, archaeological digs were underway but the legendary discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb proved elusive. In the coming years, Lord Carnarvon grew impatient with the lack of progress and informed Carter that he would remove his financial backing after one more season, if nothing could be found.

Hearing this, Carter returned to the site of the Valley of the Kings and began re-evaluating a line of huts which he had investigated some years previously. This time, he asked his employees to remove the huts as well as the debris underneath.

On 4th November 1922 a startling discovery was made by a boy who was carrying water and found himself falling over a stone. This was not just any piece of rock: this was in fact the beginning of a flight of steps.

The steps led down to a doorway decorated with seals and hieroglyphics. Immediately, Carter realised the potential of this and asked for the staircase to be filled in, so as not to reveal the potentially ground-breaking discovery. Keeping details close to his chest, he sent a telegram to Lord Carnarvon informing him and two weeks later, on 23rd November Carnarvon arrived, keen to uncover the mysteries which lay behind the sealed door.

On 26th November 1922, the first steps towards uncovering Tutankhamun’s tomb were made. Very carefully and using a chisel, Carter made a small hole in the top left hand corner of the doorway. Using a candle for light, he peered through the small gap in the doorway and was amazed to see dazzling gold treasures glistening back at him.

This was the moment, the defining moment of his career. The rest as they say was history for Carter, Lord Carnarvon and the rest of the archaeological world.

In the weeks and months that followed, precise cataloguing of the antechamber took place under the watchful eye of Pierre Lacau, director of the Department of Antiquities of Egypt. Lord Carnarvon and his daughter Lady Evelyn Herbert were frequent visitors to the burial chamber during this time.

After much laborious and intricate work, on 16th February 1923 Carter opened the sealed doorway, revealing for the first time the sarcophagus of Tutankhamun. This startling discovery was made even more special by the fact that it proved to be one of the most intact pharaonic tombs in the Valley of the Kings.

It was not long after the seal was broken and the contents revealed, that Carnarvon and Carter disagreed over the management of the tomb by the Egyptian authorities. The squabble in fact led to a temporary closure, however soon enough, Carnarvon apologised and they continued working on the tomb.

This discovery was however to be the last for Lord Carnarvon, as he passed away on 5th April 1923 after contracting blood poisoning, sparking rumours of a curse.

In no time at all, around the world press attention spiralled out of control. Speculation was rife about a curse inflicted on anyone responsible for breaking into the pharaoh’s tomb.

Over the coming years, the legend of the curse gained more traction, as some members of the excavation team died in mysterious circumstances. Whilst some dismissed this as drivel, others began to believe in the curse, fuelling further rumours.

Carter meanwhile was allowed to continue working on the site and went on to catalogue thousands of objects held within the tomb. After completing this laborious process, he subsequently retired and chose to become a collector of artefacts. He would go on to spend the latter part of his life in museums and giving lectures, inspiring and igniting interest in Egypt and Tutankhamun.

In the meantime, as the heightened level of interest in Ancient Egypt did not look as if it was abating, the speculation over the curse of the tomb continued to circulate, with the likes of Arthur Conan Doyle telling the press of an “evil elemental spirit” which was used to protect the mummy. Nevertheless, the evidence of such a curse was never found in the tomb.

Whilst many involved in the excavation went on to live long lives, the story of the mummy’s curse lives on to this day.

Sadly, in 1939, after succumbing to Hodgkinson’s disease, Howard Carter also passed away. After dedicating much of his life to the discovery of Tutankhamun, his epitaph, a quote from the Wishing Cup of Tutankhamun, appears as an apt dedication for a man who uncovered the last resting place of a legendary king:

“May your spirit live, may you spend millions of years, you who love Thebes, sitting with your face to the north wind, your eyes beholding happiness”.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 15th February 2023.