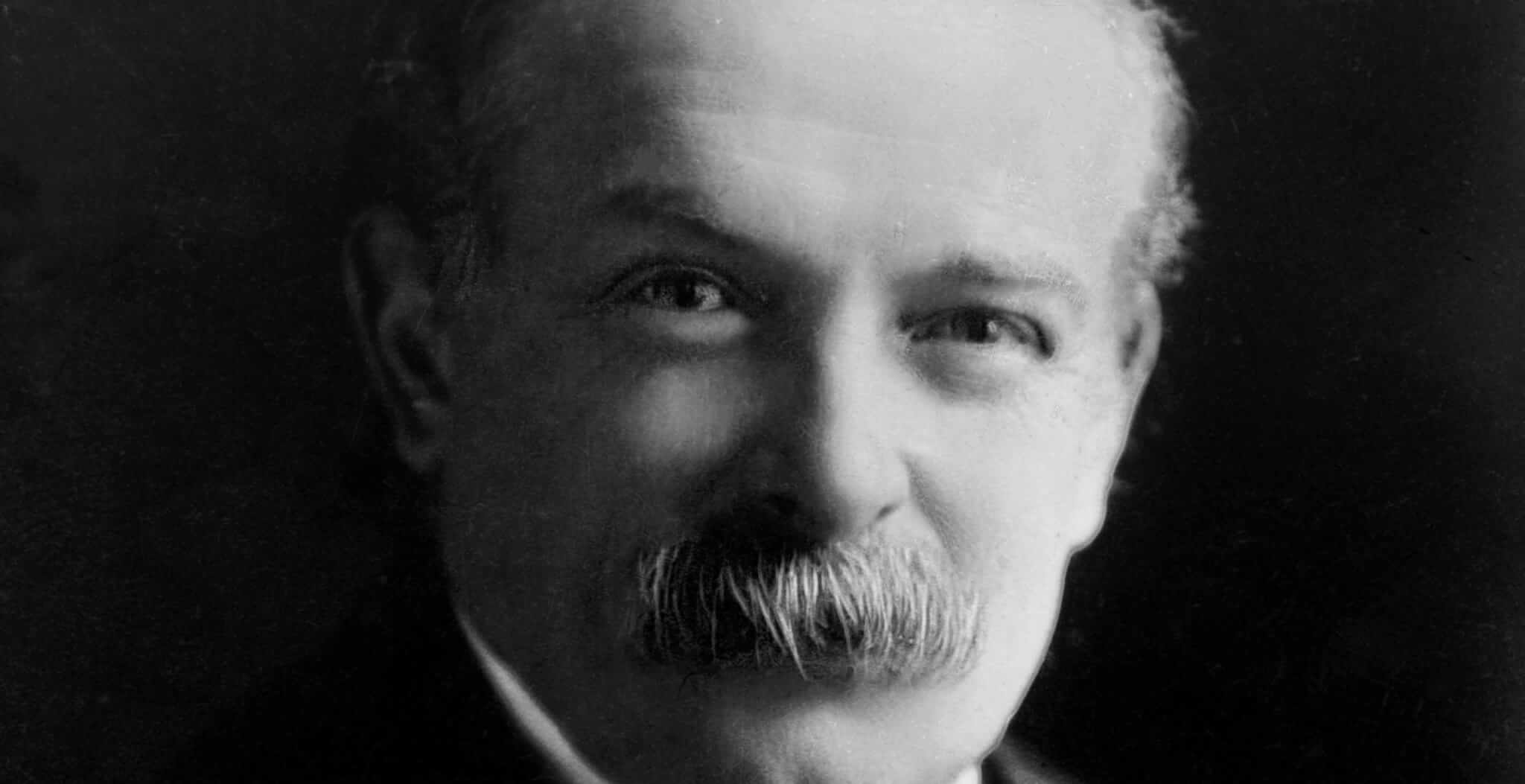

James Keir Hardie, the founder of the Labour Party was born on the 15th August 1856 in Newhouse, Scotland. He became an important Scottish politician, a pioneer of socialism in the United Kingdom and an influential trade unionist. He was a crucial political figure who became the first Labour Member of Parliament and established the movement that has become a mainstay in British politics ever since.

He was the illegitimate son of Mary Keir who worked as a domestic servant and his biological father, William Aitken, a miner who had no contact with his son. His mother Mary would later marry a ship carpenter called David Hardie and subsequently a young James would go on to take his stepfather’s name.

Hardie’s early life was difficult; the family were forced to move frequently in search of regular employment in shipbuilding. The dire family circumstances forced a young Hardie to start work at just seven years of age. He initially worked as a messenger boy, then at a bakers and also, most dangerously, he worked in the shipyard heating rivets. This early experience proved to be very traumatic for a young child forced into an adult world, particularly when a child of his age died working alongside him after falling off the scaffolding. The work was tough and unforgiving for both children and adults alike.

The precarious financial situation worsened when a lockout occurred at Clydeside shipyard forcing the workers to be sent home for a period lasting six months. With his father out of work, Hardie became the main breadwinner of the house, in the same period as one of his siblings passed away. Unfortunately for the family, a young Hardie lost his job after turning up late for work. There was no longer any other option; his stepfather was forced to work out at sea to support the family whilst his mother moved back to Lanarkshire.

Hardie, now ten, worked in the mines, operating the ventilation doors. Despite the time consuming nature of his work, his parents ensured that he could both read and write, which became paramount for his future career. Apart from being educated at home, he also joined night classes at Holytown. Whilst his work remained tough and unrelenting, his mother was guiding him towards better prospects.

In his teenage years he became known as “Keir” and was desperate to find work outside of the mines. With the help of his mother, he began learning shorthand and also joined the Evangelical Union, attending church in Hamilton where David Livingstone had also attended. Meanwhile, Keir was also became strongly aligned to the Temperance Movement after witnessing his stepfather’s alcoholism.

His participation in both the Movement and the church introduced him to the art of oration, an important step in becoming a prominent public speaker for the mining community. For many around him, his skills were to be put to use, serving as a chairman during meetings and listening to grievances. His reputation amongst the workers caused him to be blacklisted by the mine owners who viewed him with suspicion.

In 1879, the Scottish mine owners were forcing a reduction of wages, which had the effect of boosting unionisation and Keir Hardie, undeterred, was appointed the Corresponding Secretary of the miners, giving him communication with others across Scotland. Only a few months later he was appointed Miners’ Agent and his career in the trade unionist movement was flourishing. Meanwhile, the union continued to operate with small funds but he remained at the forefront, helping wherever he could, including setting up a soup kitchen in his home with his wife, Lillie Wilson.

Hardie became a sought after character due to his dynamism and hands-on approach. He continued to work in the unions but also took up journalism in order to make a living. He wrote for a local paper with pro-labour Liberal views, prompting him to join the Liberal Association and continue his work in the Temperance Movement. By 1886, Hardie’s work was beginning to bear fruit when the Ayrshire Miners Union was created with Hardie serving as Organising Secretary.

Unfortunately, Hardie quickly became disillusioned with the Liberals, questioning Gladstone’s economic policies and the impact on the working classes. Sensing there was no-one advocating strong enough reform he decided to stand for Parliament and in April 1888 he was an independent Labour candidate. Although he came last, he remained unfazed by the task ahead and later that year the Scottish Labour Party was founded with Hardie as secretary.

Hardie’s political career was gaining momentum and in 1892 he stood for the West Ham South seat and won. This was a major breakthrough for the working classes and Hardie was not afraid to make his feelings known, especially concerning the formal “parliamentary uniform” which he sought to reject. Although lambasted for this manoeuvre, Hardie focused on the issues he felt to be important such as free education, pensions, women’s right to vote and the abolition of the House of Lords. Hardie had many suggestions for reform and by 1893 with the help of others, the Independent Labour Party was formed, a worrying development for the Liberals.

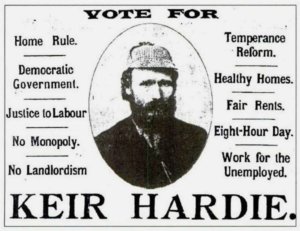

Election poster circa 1895

Election poster circa 1895

One of Hardie’s most controversial manoeuvres was when, after a terrible explosion in a Welsh mine killed many, he asked that a message of condolence be passed on. This note of sympathy was asked to be added to the congratulations issued for the birth of Edward VIII and was subsequently refused. Hardie, disgusted by the refusal, made a dramatic speech in parliament attacking the monarchy and castigating the future king. His reaction was the final nail in the coffin for many who did not agree with his reformist and revolutionary attitude, and in 1895 he lost his seat.

Despite the setback Hardie’s views and determination were unwavering and over the next five years, he made speeches and held meetings with trade unionists and socialist groups continually building the Labour movement. Hardie would also represent Labour as a junior MP in the South Wales Valleys and continued to do so until his death.

By 1906 the political landscape was changing and the Liberals won with a sweeping majority whilst, most poignantly, twenty-nine Labour MPs were elected, an important breakthrough for the party. Two years later Hardie resigned as leader but continued as a campaigner, working with the likes of Sylvia Pankhurst and also calling for an end to segregation in South Africa and self-rule in India. His pacifist tendencies won him little support during the outbreak of the First World War, when he was often heckled and booed by the crowd, yet he stuck to his principles, no matter how unpopular.

By 1915 he was in very poor health and on the 26th September he passed away. His popularity amongst politicians having been poor, no political representatives attended his funeral and the press condemned his politics and legacy. The tough and unyielding views from his critics dominated at the time, however his ideals, the party itself and the people who supported it were ultimately a much louder force.

Hardie’s legacy is evident in our political institutions today: whether loved or loathed, his belief and determination has left an indelible mark on party politics in both the twentieth and twenty-first century.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.