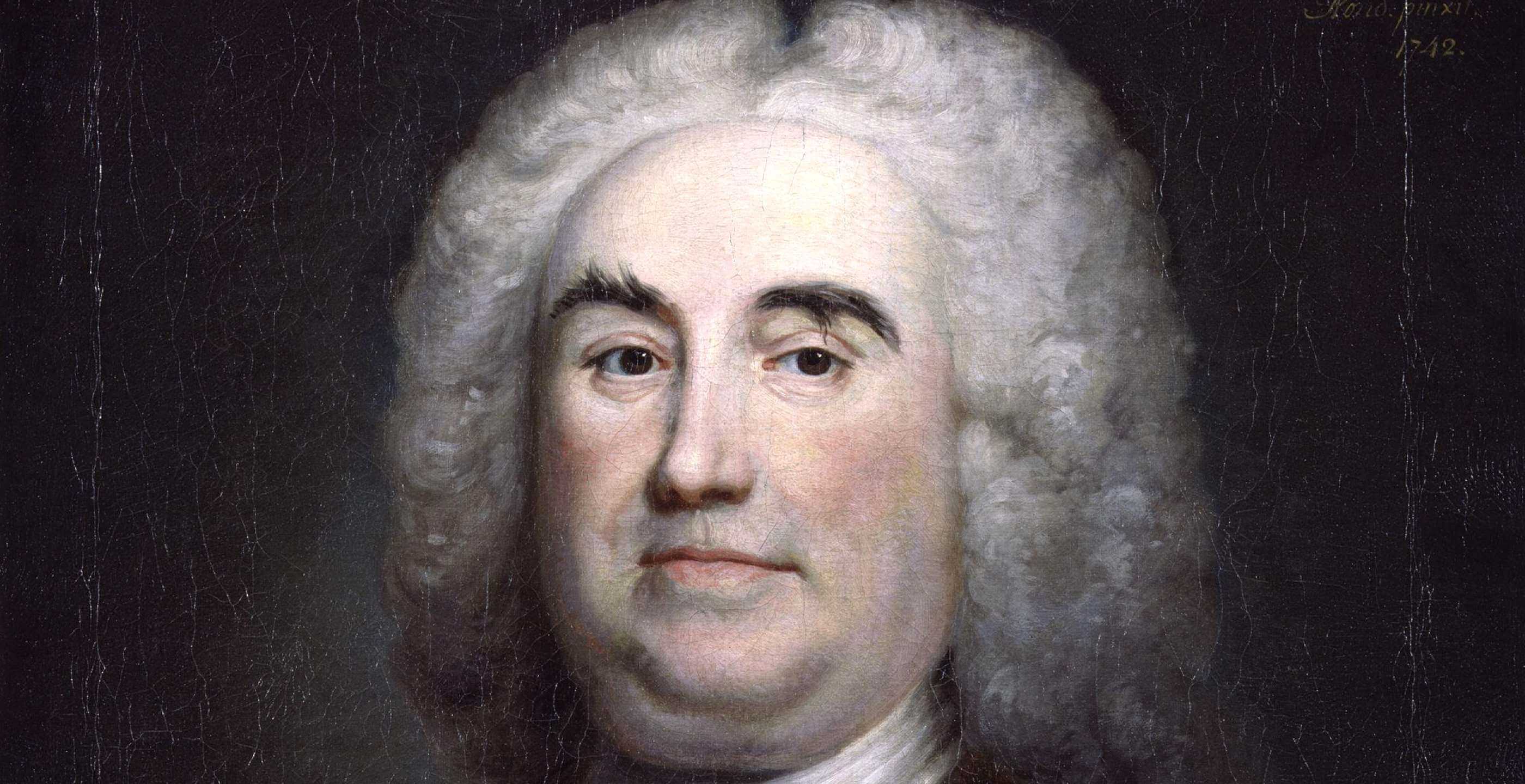

In 1714, the ascendancy of King George I marked the beginning of the House of Hanover in the British monarchy.

His life began in Germany. Born in May 1660 George was the son of Ernest Augustus, the Duke of Brunswick- Lüneburg and his wife, Sophia of Palatinate, the granddaughter of King James I. It was through his mother’s line that he would end up inheriting the throne in 1714, bypassing almost 60 Stuart claims of succession rights.

In 1682, George married his cousin Sophia however the marriage was to end in tatters, culminating in a divorce which he claimed was on the basis of discovered infidelity. Sadly for his wife though, she would find herself imprisoned in her castle, living out the rest of her days in confinement until her death in 1726.

Meanwhile, upon the death of his father and his uncles, he received the titles and lands of the Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg, which increased considerably due to a number of European wars that allowed him to expand his territory.

He soon became prince-elector of Hanover by 1708 and six years after that, upon the deaths of his mother and his second cousin Anne who was Queen of Great Britain, George succeeded the throne at the age of fifty-four.

The story of the Hanoverian succession began with the Act of Settlement in 1701 which was a momentous step in determining the future of the monarchy as well as parliament’s relationship with it. The act disregarded several hereditary claims to the throne and instead, Princess Sophia of Hanover, granddaughter of James I was made the legal heir.

The effect of deposing those other descendants of Charles I was to establish a Protestant royal lineage whilst also making clear that it was now Parliament that was authoritative on all matters of succession, bringing the legacy of the divine right of kings to a grinding halt!

Following this shunned Stuart succession in favour of the Protestant Hanoverians, George, ruler of the Duchy and Electorate of Brunswick-Lüneburg became King of Great Britain and Ireland in August 1714 and was crowned at Westminster Abbey.

George I was a Hanoverian through and through, speaking very little English. Unable to acquaint himself with the ins and outs of British political life and society he never gained considerable popularity.

From the start, George was not going to have an easy time as King of Great Britain, as continued efforts to restore the Stuart monarchy came in the form of the Jacobite Uprisings, launched numerous times and often with assistance from France.

In 1715, just one year into his reign, the Jacobites launched a challenge to regain the throne with James Francis Edward Stuart, the half-brother of Queen Anne, also known as the “Old Pretender” being the man to take George’s place.

On 6th September 1715, rebellion broke out in Braemar in Scotland, however by November the Jacobites had suffered defeat at the Battle of Sheriffmuir. Following this in 1716, the Old Pretender and his supporters, still determined in their aim, returned to France.

Trouble however was never far away and in 1722, the Atterbury Plot would lead to the arrest of the Jacobite Bishop of Rochester who faced a lifetime in exile.

The Jacobites would prove unsuccessful in their mission to depose the king. Meanwhile, some of the Tories in parliament showed themselves to have Jacobite sympathies, leading George to turn to the Whigs in order to form a government. Whilst his preference was made clear, George’s relationship with the Whigs was far from serene.

George I was faced with a new political landscape and limits on his power which he had not experienced in Germany. Whilst his language skills provided a barrier to communication, increasing his reliance on his son for translation, George would find himself consistently limited by parliament, representing a shift in the governing balance of power cementing itself in the country.

To compound matters, his relationship with his son, the Prince of Wales, also began to sour.

It was at this time that a politician began to steal the limelight: an influential Whig in the House of Commons, by the name of Robert Walpole. He seized his opportunity to impress the royals and establish himself as the first ever Prime Minister.

His ascendancy up the greasy poll of eighteenth century politics came when the crisis over the South Sea Bubble led to a frenzied and chaotic scenario that threatened the very heart of the monarchy.

The scheme had led to widespread investment, including from Walpole himself who had managed to sell when the market was at its peak, thus making a huge profit unlike so many of his compatriots.

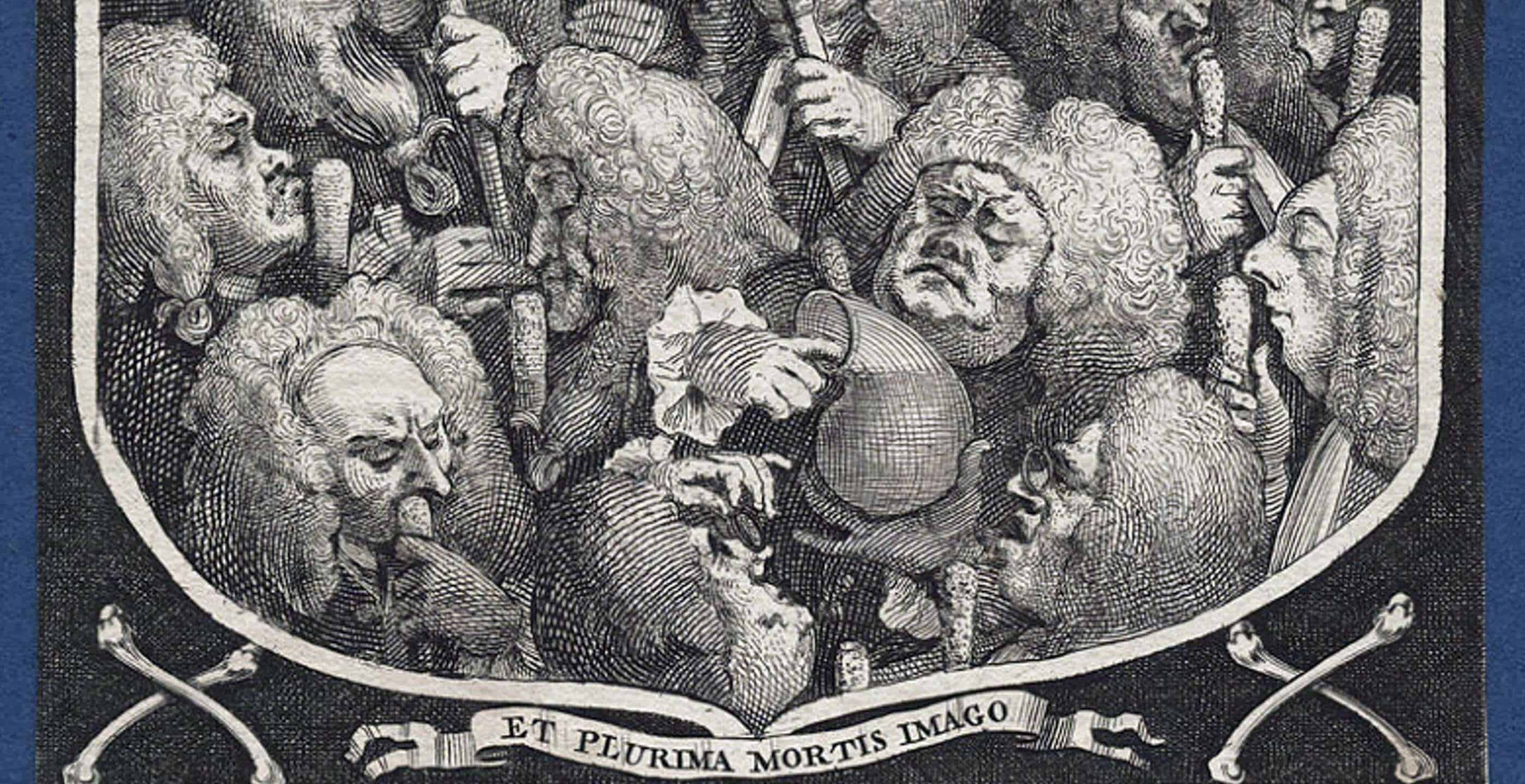

The idea was for the South Sea Company to take on the national debt of the country in exchange for bonds. The belief in this profit-making plan attracted a great deal of attention but by 1720, the company was in the process of collapsing.

The resulting impact was massive, causing thousands to lose their investments overnight. It was a financial crash with huge ramifications for the king as George I had been made governor of the company. With such close ties to the scheme, the king and all those around him became a target of discontent, threatening to invoke the Jacobite sentiment and end the Hanoverian line before it had had a chance to start.

In the midst of this mayhem, Walpole rose to the occasion and was able to not only bring calm in a moment of chaos, but was able to defend and reconcile the status of both the king and the Whig party whose association with the scheme had tainted both monarchy and parliament, earning him the nickname, “Screen-Master General”.

Walpole handled the situation with great oratory skills and political flair, allowing him to dominate the political scene by showing the public first-hand his credentials in dealing with the South Sea Bubble Crisis. The wheels were in motion for a new political power shift and Walpole was most definitely at the helm, whilst George relied on the political astuteness of this Whig politician to dig him out of a monarchical disaster.

Walpole rectified some of the damage inflicted by the financial crash by using the estates belonging to the directors of the company in order to redistribute funds to those most in need. The stock was also split between the East India Company and the Bank of England.

By 1721, Walpole was serving as First Lord of the Treasury as well as Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the Commons, establishing himself as the de facto Prime Minister by taking control of an ailing political situation. During his tenure he also helped to foil the Francis Atterbury plot and eventually quash the Jacobite tendencies, dashing any last hopes of restoring the Stuarts.

As Walpole’s political trajectory continued to prosper, so did George’s royal influence dwindle, in conjunction with this new modern system of governance. In time, George I became less and less involved in the government, leaving the fate of a nation in the capable hands of Walpole and others.

George would never regain any considerable popularity or likeability. His time in Britain had not been personally fruitful, he clearly had always felt more at home in Germany under a different system of governance and with a far greater power base.

Times were changing in Britain and the king was left to see out his reign increasingly in the background, whilst Whig-dominated politics took centre stage.

His beloved Hanover was never far from his thoughts and in June 1727 he ended his days in his homeland where he was subsequently buried.

George I’s reign marked a turning point in British history, representing the declining power of the monarchy in favour of the increasing power of government. Walpole, the recognised first Prime Minister, was to be the first in a long line of politicians to seize control in this new modern system of distributed power. George meanwhile, was to be the first in a line of Hanoverians. Succeeded by his son, the line would end with perhaps the most famous royal of them all, Queen Victoria.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: March 8, 2021.