“Born and educated in this country, I glory in the name of Britain.”

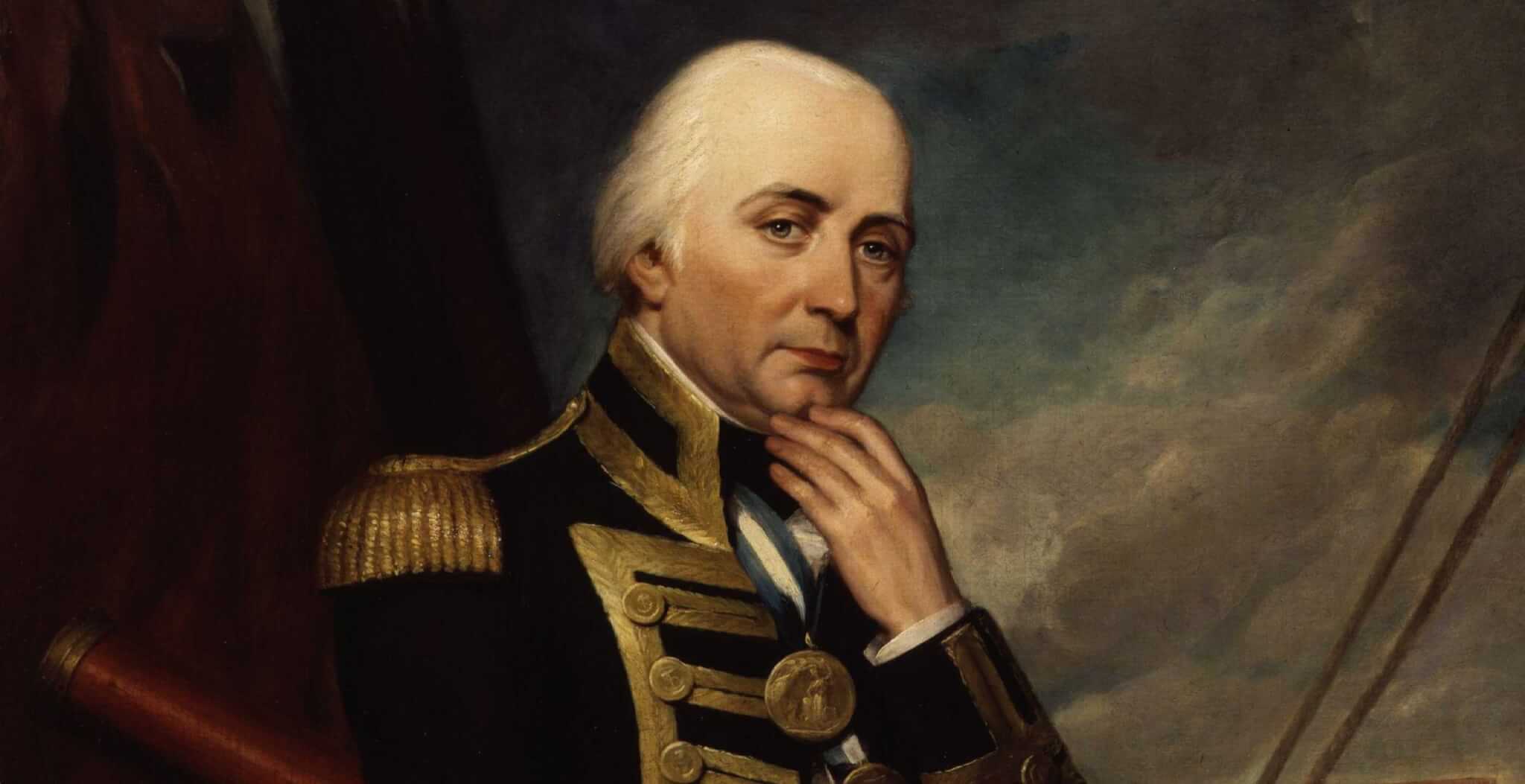

These were the words of King George III, the first in the Hanoverian line to not only be born and raised in England, to speak English with no accent but also to never visit his grandfather’s homeland of Hanover. This was a king who wanted to distance himself from his German ancestors and establish royal authority whilst presiding over an increasingly powerful Britain.

Sadly for George, he would not achieve all of his goals as during his reign, more than ever, the balance of power had shifted from the monarchy to parliament and any attempt to recalibrate it fell short. Moreover, whilst the successes of colonisation abroad and industrialisation led to increased prosperity and the flourishing of arts and science, his reign would become most well-known for the disastrous loss of Britain’s American colonies.

George III began his life in London, born in June 1738, the son of Frederick, Prince of Wales and his wife Augusta of Saxe-Gotha. When he was still just a young man, his father died at the age of forty-four, leaving George to become heir apparent. Now seeing the line of succession differently, the king offered his grandson St James’s Palace on his eighteenth birthday.

Young George, now Prince of Wales, refused his grandfather’s offer and remained guided predominantly by the influence of his mother and Lord Bute. These two figures would remain influential in his life, guiding him in his matrimonial match and also later in politics, as Lord Bute would go on to become Prime Minister.

In the meantime, George had shown interest in Lady Sarah Lennox, who sadly for George, had been deemed an unfit match for him.

By the time he was twenty-two however, his need to find a suitable wife became even more pressing as he was about to succeed the throne from his grandfather.

On 25th October 1760, King George II suddenly died, leaving his grandson George to inherit the throne.

With the marriage now a matter of urgency, on 8th September 1761 George married Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, meeting her on the day of their wedding. The union would prove to be a happy and productive one, with fifteen children.

Only two weeks later, George was crowned at Westminster Abbey.

As king, George III’s patronage of the arts and sciences would be a dominant feature of his reign. In particular, he helped fund the Royal Academy of Arts and also was a keen art collector himself, not to mention his extensive and enviable library which was open to the country’s scholars.

Culturally he would also have an important impact, as he chose unlike his predecessors to remain in England for much of his time, only journeying down to Dorset for holidays which began the trend for the seaside resort in Britain.

During his lifetime, he also extended the royal households to include Buckingham Palace, formerly Buckingham House as a family retreat as well as Kew Palace and Windsor Castle.

Further afield scientific endeavours were supported, none more so than the epic journey taken by Captain Cook and his crew on their voyage to Australasia. This was a time of expansion and realising Britain’s imperial reach, an ambition which led to gains and losses during his reign.

As George took the throne, he found he was dealing with a very different political situation to that of his predecessors. The balance of power had shifted and parliament was now the one in the driving seat whilst the king had to respond to their policy choices. For George this was a bitter pill to swallow and would lead to a series of fragile governments as the colliding interests of monarchy and parliament played out.

The instability would be presided over by a number of key political figures leading to resignations, some of these reinstated, and even expulsions. Many of the political stand-offs which unfolded took place against the backdrop of the Seven Years’ War which led to an increasing number of disagreements.

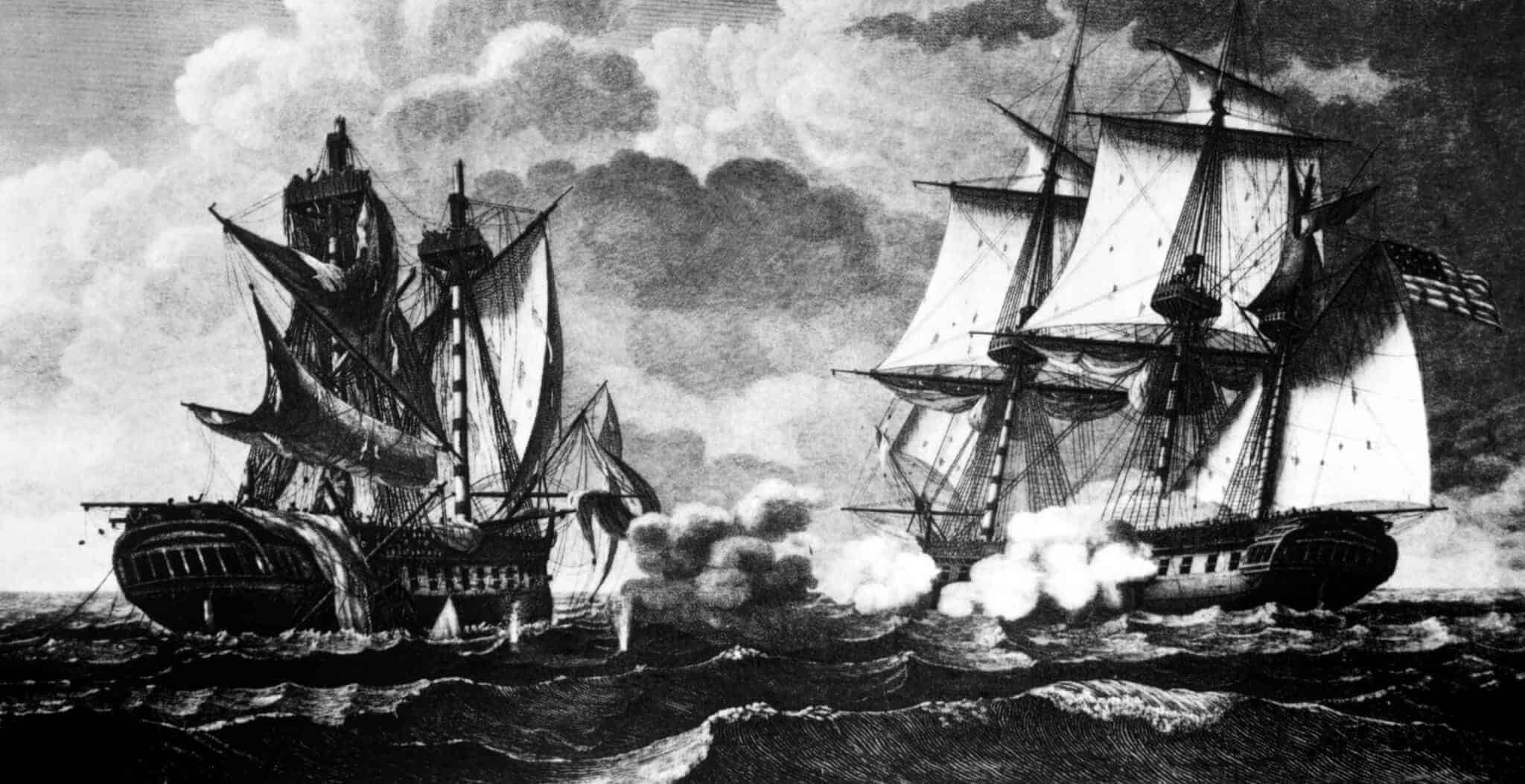

The Seven Years War, which had begun in the reign of his grandfather, met its conclusion in 1763 with the Treaty of Paris. The war itself had inevitably proved fruitful for Britain as she established herself as a major naval power and thus a leading colonial power. During the war, Britain had gained all of New France in North America and also managed to capture several Spanish ports which were traded in exchange for Florida.

Meanwhile, back in Britain the political wrangling continued, made worse by George’s appointment of his childhood mentor, the Earl of Bute as chief minister. The political infighting and struggles between monarchy and parliament continued to boil over.

Moreover, the pressing issue of the Crown’s finances would also become difficult to handle, with debts amounting to more than £3 million during George’s reign, paid by Parliament.

With attempts at staving off political dilemmas at home, Britain’s biggest problem was the state of its thirteen colonies in America.

The problem of America for both king and country had been building for many years. In 1763, the Royal proclamation was issued which limited expansion of American colonies. Moreover, whilst attempting to deal with cash flow problems at home, the government decided that Americans, who were not taxed should contribute something towards the cost of defences in their homeland.

The tax levied against the Americans led to animosity, mainly due to the lack of consultation and the fact that Americans did not have any representation in parliament.

In 1765, Prime Minister Grenville issued the Stamp Act which effectively instigated a stamp duty on all documents in the British colonies in America. In 1770, Prime Minister Lord North chose to tax Americans, this time over tea, leading to the events of the Boston Tea Party.

In the end, conflict proved inevitable and the American War of Independence broke out in 1775 with the Battles of Lexington and Concord. A year later the Americans made their feelings clear in an historic moment with the Declaration of Independence.

By 1778, the conflict had continued to escalate thanks to the new involvement of Britain’s colonial rival, France.

With King George III now viewed as a tyrant and with both king and country unwilling to give in, the war dragged on until a British defeat in 1781 when news reached London that Lord Cornwallis had surrendered at Yorktown.

After receiving such dire news, Lord North had no option but to resign. The subsequent treaties that followed would force Britain to recognise the independence of America and return Florida to Spain. Britain had been underfunded and overstretched and her American colonies were gone for good. Britain’s reputation was shattered, as was King George III.

To compound issues further, an ensuing economic slump only contributed towards the febrile atmosphere.

In 1783, a figure came along who would help change the fortunes of Britain but also George III: William Pitt the Younger. Only in his early twenties, he became an increasingly prominent figure at a difficult time for the nation. During his time in charge, George’s popularity would also increase.

Meanwhile, across the English Channel political and social rumblings exploded leading to the French Revolution of 1789 whereby the French monarchy was deposed and replaced with a republic. Such hostilities threatened the position of landowners and those in power back in Britain and by 1793, France had turned its attentions to Britain by declaring war.

Britain and George III resisted the feverish atmosphere of the French revolutionary zealots until the conflict eventually concluded with the defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

In the meantime, George’s eventful reign also bore witness to the coming together of the British Isles in January 1801, as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. This unity was not however without its problems, as George III resisted Pitt’s attempts to alleviate some of the legal stipulations against the Roman Catholics.

Once more, political divisions shaped the relationship between parliament and monarchy however the pendulum of power was now swinging very much in favour of parliament, especially with George’s health continuing to decline.

By the end of George’s reign, poor health had led to his confinement. Earlier bouts of mental instability had wrought complete and irreversible damage on the king. By 1810 he was declared unfit to rule and the Prince of Wales became Prince Regent.

Poor king George III would live out the rest of his days confined in Windsor Castle, a shadow of his former self, suffering from what we now know to be a hereditary condition called porphyria, leading to his entire nervous system being poisoned.

Sadly, there was no chance of recovery for the king and on 29th January 1820 he died, leaving behind a somewhat tragic memory of his descent into madness and ill health.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: March 24, 2021.