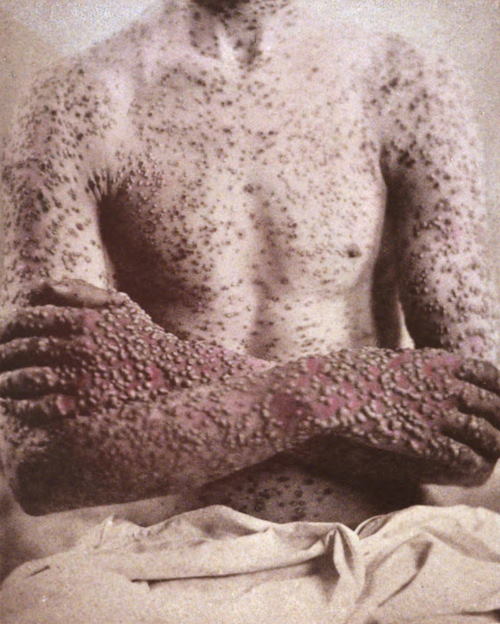

Just over 300 years ago, in April 1721, a smallpox epidemic was raging in England. The aristocratic writer Lady Mary Wortley Montagu was shut up in her house in Twickenham to escape infection, sending her servants out to glean news of the dead.

January had been unseasonably warm in England that year. Smallpox seemed to ‘go forth like a destroying Angel.’ Mary lost a young cousin, Lady Hester Feilding, to the disease in the first few months as well as her great friend and neighbour, James Craggs.

Seven years earlier, Mary’s beloved only brother had died from the smallpox. When she also fell ill, only two years after her brother’s death, she narrowly escaped with her own life. Her skin now bore the tell-tale scars left by the disease. Her eyes suffered too. She could never look at bright light again. She also lost all her eyelashes and forever afterwards had what her friends referred to as ‘the Wortley stare.’

Soon after her own battle with smallpox, Mary went to live in Constantinople with her husband, who had been made the British ambassador there, along with young son Edward. Their only daughter, young Mary, was born during their time living in Turkey.

There, Lady Mary had witnessed the Turks employing a technique known as ‘engraftment’ against smallpox. A small sample of pus would be taken from someone who had the disease, wounds opened on the wrists and ankles of the volunteers, and the pus mixed into their bloodstreams.

Another term for ‘engrafting’ was ‘inoculation’- a word taken from botany, literally meaning ‘in-eyeing’.

As a result of inoculation, smallpox was far less virulent in Turkey than it was back in England. Mary was the first Western woman to be invited to dine alone with the wives of senior Turkish officials. Her hostesses there assured her that inoculation was totally safe.

The previous British ambassador to Turkey had ensured his two sons were inoculated before they returned home, so Lady Mary was determined to protect her own son as well while she was there. When her husband was away on diplomatic business, she and their household surgeon, Dr Maitland, had young Edward inoculated. Young Mary was still only a babe in arms at the time, so her mother decided against protecting her as well.

Lady Mary was shrewd enough to recognise that doctors would be wary of introducing inoculation back in England. After all, they would stand to lose the fees they charged for attending the bedsides of their many smallpox patients.

When Mary’s husband was recalled to England, and the family returned home, they found that smallpox outbreaks back here were becoming ever more frequent and severe. There was yet another outbreak the year after their return. Despite knowing that she had a solution and that her little daughter was at risk, Mary kept quiet.

But a couple of years later, in 1721, spurred on by the deaths of those close to her, Mary decided to take action. She was no longer prepared to leave her 3-year-old daughter unprotected.

She wrote to Dr Maitland, the surgeon who had been with them in Turkey, summoning him to Twickenham. The reason for her request she kept deliberately vague, in case her letter was intercepted.

When he arrived, Maitland was nervous. Mary’s husband was yet again absent. He would surely disapprove of their actions? Maitland’s own professional reputation was also at risk. But Mary’s iron will won the day. She held young Mary still, while Maitland used his surgeon’s lancet to make the shallow wounds and inoculate the little girl against the deadly disease.

After just ten days young Mary ran a temperature and displayed a few harmless spots. Lady Mary invited ‘Several Ladies and Other Persons of Distinction’ to visit the sick room and inspect the patient. Mary kept a protective guard at the nursery door, while the little girl smilingly allowed herself to be examined, unaware that she was the first person in the West to be inoculated.

One of these people was a physician named Dr James Keith. He had lost his two oldest sons to the smallpox in the 1717 outbreak, when Mary herself had fallen ill. HIs only surviving son Peter was born soon afterwards and Dr Keith now asked if they would inoculate Peter.

Dr Maitland – only a humble surgeon – was in awe of the eminent Dr Keith, so it was agreed that young Peter should be bled and purged before the inoculation, even though Mary and Maitland knew it was unnecessary. He survived.

The medical profession at first mistrusted Mary’s new-fangled inoculation. But eventually they accepted it, provided it was accompanied by bleeding and purging. From the start, Mary pointed out that bleeding and purging were potentially dangerous, weakening the patient.

For the next few years Mary spent much of her time travelling in her coach between friends’ households, inoculating whoever asked for her help- masters and servants alike. Her daughter, young Mary – who often travelled with her – remembered the ‘looks of dislike’ that often greeted them and the ‘significant shrugs’ of sceptical bystanders.

Lady Mary told her family that nearly every day for the rest of her life she would regret having put the process in motion. She saw for herself ‘what an arduous, what a fearful and, we may add, what a thankless enterprise it was.’

When young Mary grew up, she fell in love with John Stuart, Earl of Bute. Her parents opposed the marriage but agreed that it could take place. Lady Mary made the mistake of telling her daughter what she thought of Bute. In her opinion he was honest but inclined to be hot-tempered. Inevitably this caused a rift between mother and daughter.

The Earl and Countess of Bute had a good marriage, with eleven surviving children. They shared a love of gardening and were instrumental in the creation of Kew Gardens.

As for Lady Mary herself, she went to live abroad for over twenty years, separated from her husband. She and her daughter were gradually reconciled in the letters they wrote to each other.

When Lady Mary’s husband died, she finally returned home to London, knowing that she herself had breast cancer and did not have long to live. She was reunited with her daughter and the son-in-law she had not thought much of. During Lady Mary’s few months in London, he became Prime Minister.

By Jo Willett. ‘The Pioneering Life of Mary Wortley Montagu: Scientist and Feminist’ is due for publication by Pen & Sword Books in April 2021 (the 300th anniversary of Mary’s inoculation experiment). Jo has been an award-winning TV drama producer all her working life.