On September 3rd, 1939, the British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, told us “… this country is at war with Germany.”

His words will stay indelibly etched in my memory — even though I was just a six-year-old boy. I had no idea of the seriousness of the occasion, but my parents obviously did. They remembered World War One.

My immediate concern was that if the war lasted more than a week or two, it might interfere with my plans for my seventh birthday, September 29, Michaelmas. I was expecting a chemistry set.

I could make the Prime Minister some gun powder, I thought. “‘E could ‘ave someone chuck it at ‘itler. That’ll take care of ‘im.” Better than any plan the British government seemed to have at the time.

When the 29th came, I changed water into wine and used the charcoal from a spare gas mask to make brown sugar white. And that led me into the dark world of the black market.

Enter rationing. No meat and dairy products? No problem. Shortage of vegetables? Who cares? Strict limits on sweets? Now that was bloody serious. But petrol was first. Its availability for personal use was controlled. Fuel for war-related or commercial activities was dyed red. Misusing it was a punishable offence.

Mr. Montgomery, who was in the limousine business, was particularly interested in my experiments. “If you can do that with sugar, then maybe you can take the colour out of this?” He presented me with a can of restricted-use, red-dyed petrol. “I’ll make it worth your while,” he added. I didn’t know what my while was worth, but the can of colourless petrol I presented to him earned me half-a-crown. I learned, much later, how he exploited my finding.

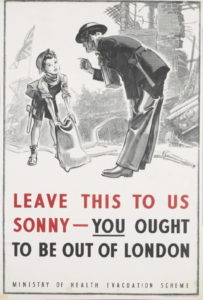

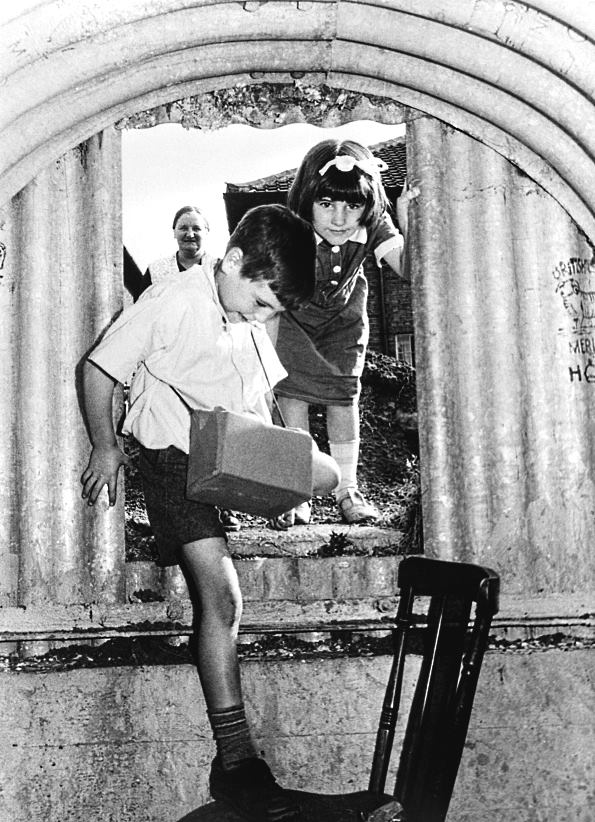

I was initially evacuated to Guildford in Surrey. To “Rookwood.” Surrounded by “acres of green,” the imposing mansion was another world. Servants, gardeners, and fog-free air. On the other hand, I had to deal with a pain-inflicting, sadistic schoolmaster who openly despised Londoners.

A brief stay in Frome, Somerset, came later. My grammar school had temporarily relocated there from London. More pain-inflicting schoolmasters. Not because we were Londoners; just because we were available.

I was nearly eight when I was scheduled to sail on the British passenger ship, the SS City of Benares, leaving Liverpool for Canada on September 13th, 1940. I was then unscheduled. Never knew why. Four days later, the German submarine U-48 torpedoed the City of Benares. Tragically, seventy-seven of the ninety children on board died at sea.

After the war, the captain of U-48, Kapitanleutnant Heinrich Bleichrodt, was charged with sinking the ship knowing that it was transporting evacuees. He was duly acquitted and died peacefully. An old man. In Germany, at home. In his bed. Surrounded by the many medals bestowed upon him by Adolph Hitler.

Sieg bloody heil!

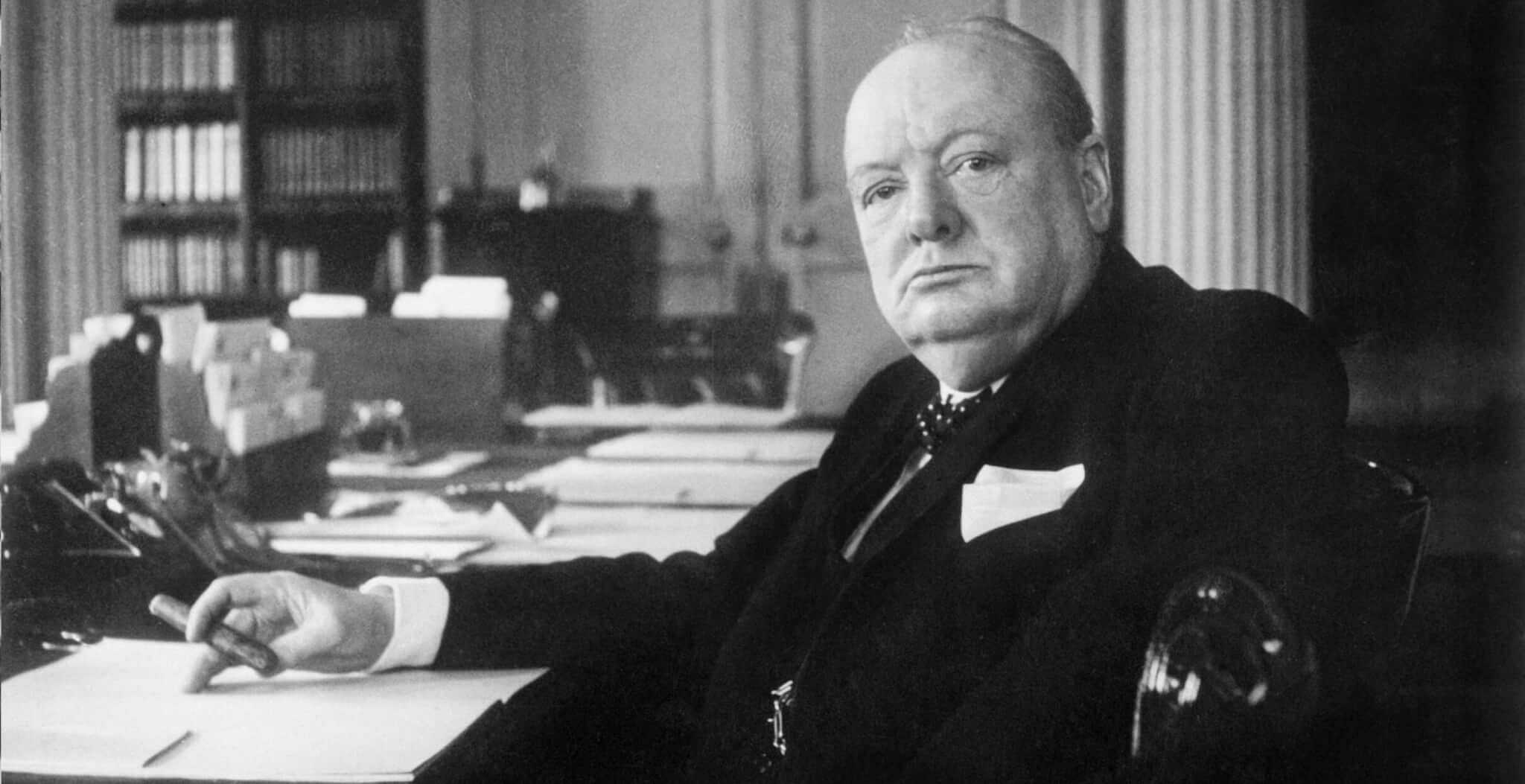

Even as a small boy, I could appreciate how important the BBC was. And the most important program, at least in our house, featured The Right Honourable Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill. Winnie.

When Churchill addressed the nation, my mother immediately stood to attention. Well, it seemed that way. Armed with paper and pen, she used her fast and accurate shorthand to record all of Churchill’s speeches. Probably captured his every lisp and stammer too.

While the radio wasn’t much fun for kids, a few comedy programs helped. One of my favourites was “ITMA: It’s That Man Again.” Making fun of Hitler always made him seem less frightening.

A weekly address by the traitor, William Joyce, almost fell into the comedy category. Nicknamed Lord Haw-Haw, we laughed at everything he said. Joyce was later found guilty of treason and hanged.

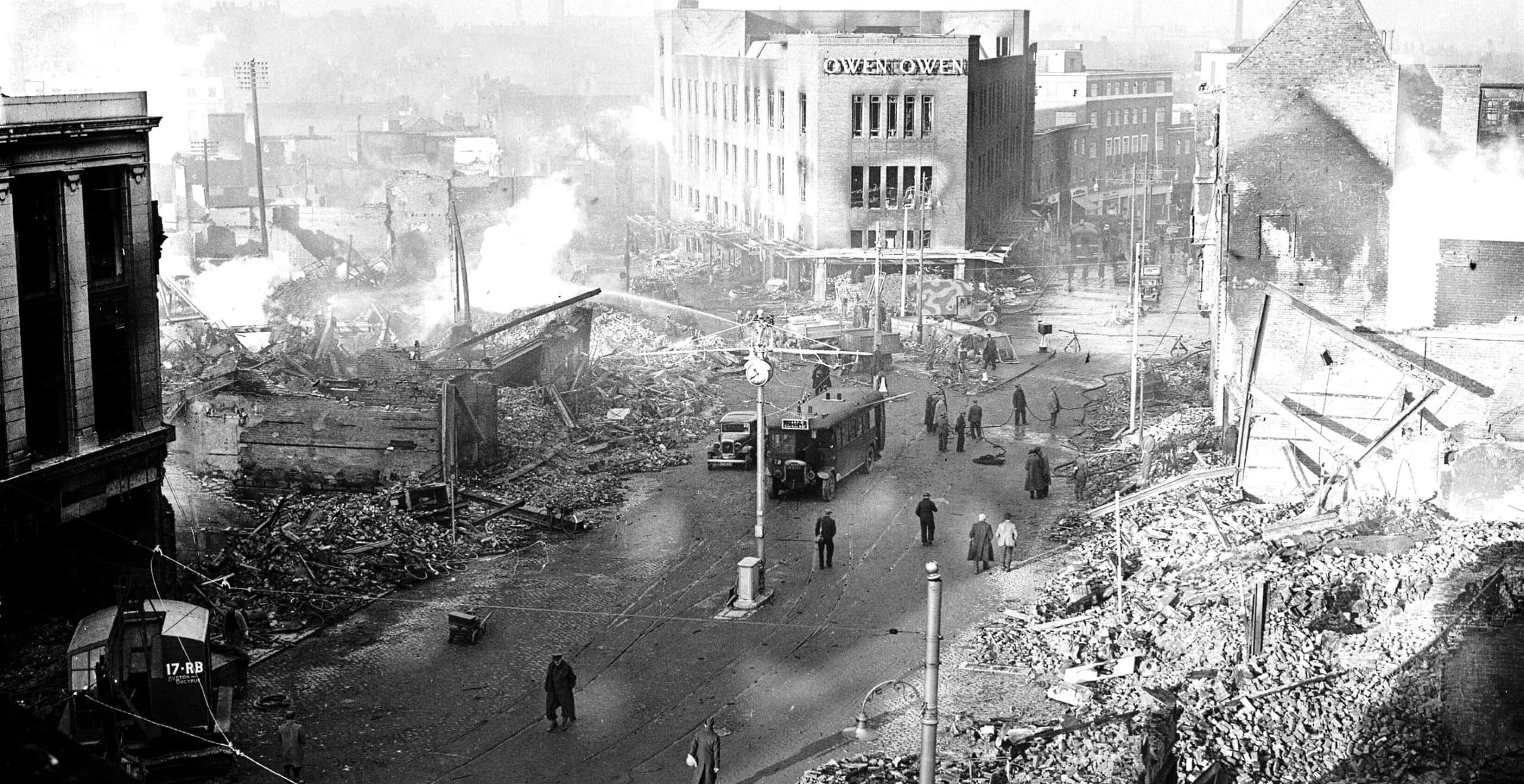

I saw Winnie once. Up close. Following a brutal air raid, he visited and watched while our neighbours and friends were digging through rubble, looking for other neighbours and friends. I was disappointed that he didn’t invite us to join him for tea and biscuits.

A week later, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth came to call. They didn’t invite us to join them either.

From my perspective, the Blitz was, above all, exciting. Initially, anyway. And, with typical British aplomb, those around me simply “got on with it.”

Brit Grit at its best.

Daytime air raids came first. Target: the East End of London. Right where I lived. The skies filled with planes – twisting and turning. Pursuing and pursued. Surely this was the ultimate spectacle for a young boy.

Night time raids followed. Less to see; no less to fear.

Following the “All Clear” siren, like vultures swooping down on carrion, my friends and I would roam the streets gathering the scattered, jagged fragments of shrapnel. I was very proud of my collection.

I heard my mother and her friend talking about a neighbourhood teenage girl who was “sex mad.” “She slept around,” they said. I didn’t know what sex mad was, but I must be too. I’d also been sleeping around. In different shelters. All over London. Street Shelters, Anderson Shelters, Morrison Shelters, and the platforms of London tube stations.

My father, too old and unfit for active duty, was an Air Raid Precaution warden. And the ARPs need for boys, aged 14 to 18 as messengers, was appealing; I’d become an RAF Spitfire pilot later. Unfortunately, they didn’t wait for me.

In June, 1944, the Germans introduced their “weapons of retaliation.” They called them Vergeltungswaffen. First came the V-1s. Londoners called them flying bombs, buzz bombs, doodlebugs, anything to avoid saying Vergeltungswaffen. That would be too bloody difficult. And so…unEnglish.

If a V-1 was overhead when its engine cut out, we had about twelve seconds to know whether the next explosion was to be the last thing we’d ever hear. That period of silence became increasingly terrifying. To wait for the explosion. To wait for death.

Their unstoppable, high-altitude V-2 rockets were next. But at least Allied bombing rendered the V-3, a long range supergun, unusable. The V-4, the V-4-Victory hand gesture, popularized by Churchill, was ours. A symbol of defiance and hope.

Some fifty years after the end of World War II, my wife and I visited the places where I’d lived and/or attended school during the war.

British Street? My street? Gone! Cannibalized by the adjacent hospital. Coopers, my grammar school in London? Founded in 1536. Moved. The Kings Arms pub at the end of British Street? Been there since 856 BC. Not any longer. It was enough to drive me to drink — if I could get one. “Rookwood” and its magnificent grounds? Now dozens of upscale townhouses. Coopers temporary school in Frome? Couldn’t find anyone old enough to remember where it was.

But the places I’d lived in and the schools I’d attended weren’t really that important. The people in my early life in England were. Sadly, my wartime family, friends, and neighbours were all gone too.

“Fings ain’t wot they used t’be.”

After completing his BSc and PhD degrees at Imperial College, London and a long career in pharmaceutical research, Charles Berkoff published his award-winning novel, ‘PreMedicated Murder’. His World War Two memoirs followed. He lives in Sarasota, Florida, with his wife, Heide, and his rescue dog, Landy. www.charlesberkoff.com.