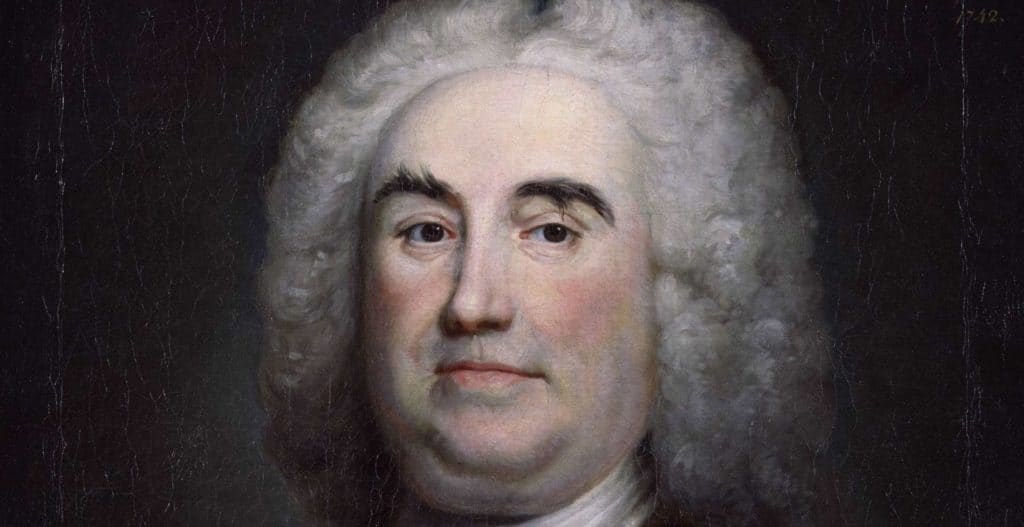

Robert Banks Jenkinson, Lord Liverpool is not generally viewed as one of Britain’s greatest prime ministers – Disraeli’s sneer at him as the “Arch-mediocrity” in his 1844 novel ‘Coningsby’ is only too well remembered. Yet, as my new book ‘Britain’s Greatest Prime Minister’ shows, when you look at what he achieved, as a wartime and a peacetime leader, he deserves to rank very high indeed.

Liverpool’s greatest achievements were in economics, not the strong point of Disraeli, or of Liverpool’s remarkably few biographers. As War Secretary in 1809-12, he devised an economic and military strategy to beat Napoleon that relied on constant moderate pressure over several years, rather than the massive short-term coalitions that had previously been unsuccessful. By capturing France’s remaining colonies and the attritional Peninsular War, he increased the pressure on France’s loot-driven economy until Napoleon was forced into an invasion of Russia in 1812 that proved fatal.

After 1812 as prime minister, Liverpool increased the pressure further, providing subsidies to Britain’s potential allies, and pulling together a coalition that won the key Battle of Leipzig in October 1813. The road to victory was a rocky one, however; in June 1813 Liverpool and Vansittart (Chancellor of the Exchequer) were reduced to begging the Bank of England for Treasury bill rollovers week by week, until Wellington’s victory at Vitoria improved Britain’s credit standing.

As victory approached, Liverpool set out the basis for a peace settlement, which Castlereagh (his Foreign Secretary) followed at the Congress of Vienna. Instead of punishing Britain’s enemies after victory, Liverpool decided on a peace that imposed no direct reparations, left France with most of her colonies and brought Britain no additional colonial gains. His moderation, and the deft management of Castlereagh and the Austrian minister Metternich, produced a European peace that lasted for almost 100 years. Their distant successors at the 1919 Congress of Versailles would have done well to follow their example.

The Waterloo campaign was also a masterpiece of organization, with Wellington (then in Vienna) assembling the Allies into a coalition as soon as Napoleon’s return was known, and Vansittart raising £27 million of Consols four days before Waterloo – forty times the funds that Napoleon had available.

Once peace was restored, Liverpool faced three economic problems. The government debt was far too high, the highest it has ever been in terms of the economy. The pound was unanchored, its value governed largely by the Bank of England’s note issues; Liverpool believed the country should return to gold. Agriculture had been over-expanded during the war, with marginal lands planted. Liverpool believed some protection was necessary, to avoid bankrupting landholders and ensure the maximum food self-sufficiency in any future war.

Liverpool tackled the agriculture problem first with Corn Laws that allowed free imports if the corn price was above 80 shillings per quarter, but blocked imports below that price. This allowed farmers to adjust; it also stimulated corn growing in Ireland, which since 1806 could sell freely into the rest of the U.K. 30 years later, Irish corn crops were a modest offset to the notorious potato famine.

The debt was the biggest problem. Vansittart reduced non-debt-service public spending by 69% in three years, balanced the budget, and kept it balanced, raising taxes in 1819 to do so. Liverpool passed legislation that year returning Britain to the Gold Standard, which took effect in 1821. Sound debt management and the Gold Standard helped Britain’s credit rating and reduced interest rates, so holders of Consols (which had no maturity) received a capital gain of over two thirds of national output in the nine years 1815-24. That capital gain financed the industrial take-off of the early 1820s, and offset the deflation caused by the return to gold (prices fell by 40% in the same period). By the time Liverpool left office, economic growth had made the debt much less burdensome – Victorian chancellors like Gladstone had it very easy by comparison.

The first few years after the war were difficult. There was a deep recession in 1816-17, following the crop failure of the 1816 “Year without a summer” then another painful recession in 1819-20 caused by the deflation accompanying the return to gold. Both recessions caused unrest, which Liverpool and his Home Secretary Lord Sidmouth handled deftly. Sidmouth used informants to watch for revolution, arresting the participants in the 1820 Cato Street Conspiracy before they could break into a Cabinet dinner and assassinate the ministers, for example. The Peterloo massacre, caused by inept Manchester magistrates, was a blot on the government’s record, but overall, order was maintained. Unrest died down once prosperity returned after 1820.

One useful reform in these years was the Savings Banks Act of 1817, by which Trustee Savings Banks were set up, investing only in government bonds, to provide safe havens for worker savings. Liverpool’s next major innovation was to move the country towards free trade, which he did by a speech in May 1820, setting the path for British trade policy for the next 40 years, and opening British business to the world.

After 1820, things became easier as the economy recovered and then boomed. Taxes were reduced, as the budget was now in surplus. Peel, the new Home Secretary, instituted numerous legal reforms, and trades unions were legalized by 1824 and 1825 legislation.

At the end of 1825, a financial crash occurred, caused mainly by speculation by the English country banks, of which there were more than 800 (no bank was allowed to have more than six partners). Liverpool had warned against the speculation the previous March. After the crash he reformed the banking system, allowing the formation of joint stock banks, restricting note issues except by the Bank of England, and pushing the Bank of England to open branches. The new laws were passed early in 1826, and by the end of 1826 the post-crash recession had lifted.

Liverpool had major achievements in both war and peace over 15 years – for one thing, he won four successive general elections, more than any other prime minister. Although his main expertise was in economic policy, he produced an excellent post-war peace settlement and embarked on major programs of legal and social reform. Without his work, the Victorians’ lives would have been much less contented and prosperous. In war and peace, when you look at Britain’s 55 prime ministers, Liverpool deserves to rank No. 1.

Martin Hutchinson was born in London, brought up in Cheltenham, England, and has lived in Singapore, Croatia, London, suburban Washington, and since 2011 in Poughkeepsie, NY. He was a merchant banker for more than twenty-five years before moving into financial journalism in 2000. He earned his undergraduate degree in mathematics from Trinity College, Cambridge, and an MBA from Harvard Business School. Pre-order the new book ‘Britain’s Greatest Prime Minister’.