The Guildhall in the middle of Chard in Somerset, might seem an unlikely place to celebrate the life of a local woman who made political history, as well as championing workers rights and equal opportunities for women.

There on the wall, however, is a blue plaque – prominently displayed to the side of the main columns. The town’s pride in one of its former citizens is clear in the opening part of the inscription’s layout:

‘Margaret Bondfield: The first woman Cabinet Minister…WAS BORN IN THIS TOWN’

Margaret Bondfield’s political achievements form only part of her story, as she blazed a trail in the early part of the 20th century for future social reformers and activists. Nevertheless, January 1924 marks the 90th anniversary of a unique event – her appointment as the first ever female British government minister. A step that was to lead to even greater things five years later.

Margaret was born in 1873, the second youngest of eleven children. At this time, Chard was a busy industrial town – with lace making; the cloth trade and iron working among its trades. Margaret grew up in a family environment that encouraged social fairness and an interest in working class political movements. She was later to write in her book, ‘A Life’s Work’, that …”the old radicalism and nonconformity of Chard…must somehow have got into the texture of my life and shaped my thoughts….” Her anger at injustice may also have been stirred by her father’s dismissal from his lace factory job, after many years as a foreman, when Margaret was only a child.

Attending the local High Street School, the young Margaret was a bright and conscientious student, showing an interest in wider issues. At fourteen however, her life was to change drastically. Following a visit to see relatives in Brighton and keen to start working after leaving school, Margaret was offered an apprenticeship at a draper’s shop in the city. It would be several years before she saw her family again and, although she didn’t know it at the time, the job would set her on the path to political activism and eventual high office.

Although treated well by the shop owner, Mrs White, the long working hours and living-in conditions made a deep impression on Margaret. Mixing with other shop girls, she saw how the daily grind wore down the women and affected their self-respect – leaving them little time or energy to pursue interests away from work. Many of the girls just seemed intent on getting married as early as possible in order to escape the drudgery of shop work. Margaret did not want to follow the same path, but determined to help improve conditions for ordinary workers.

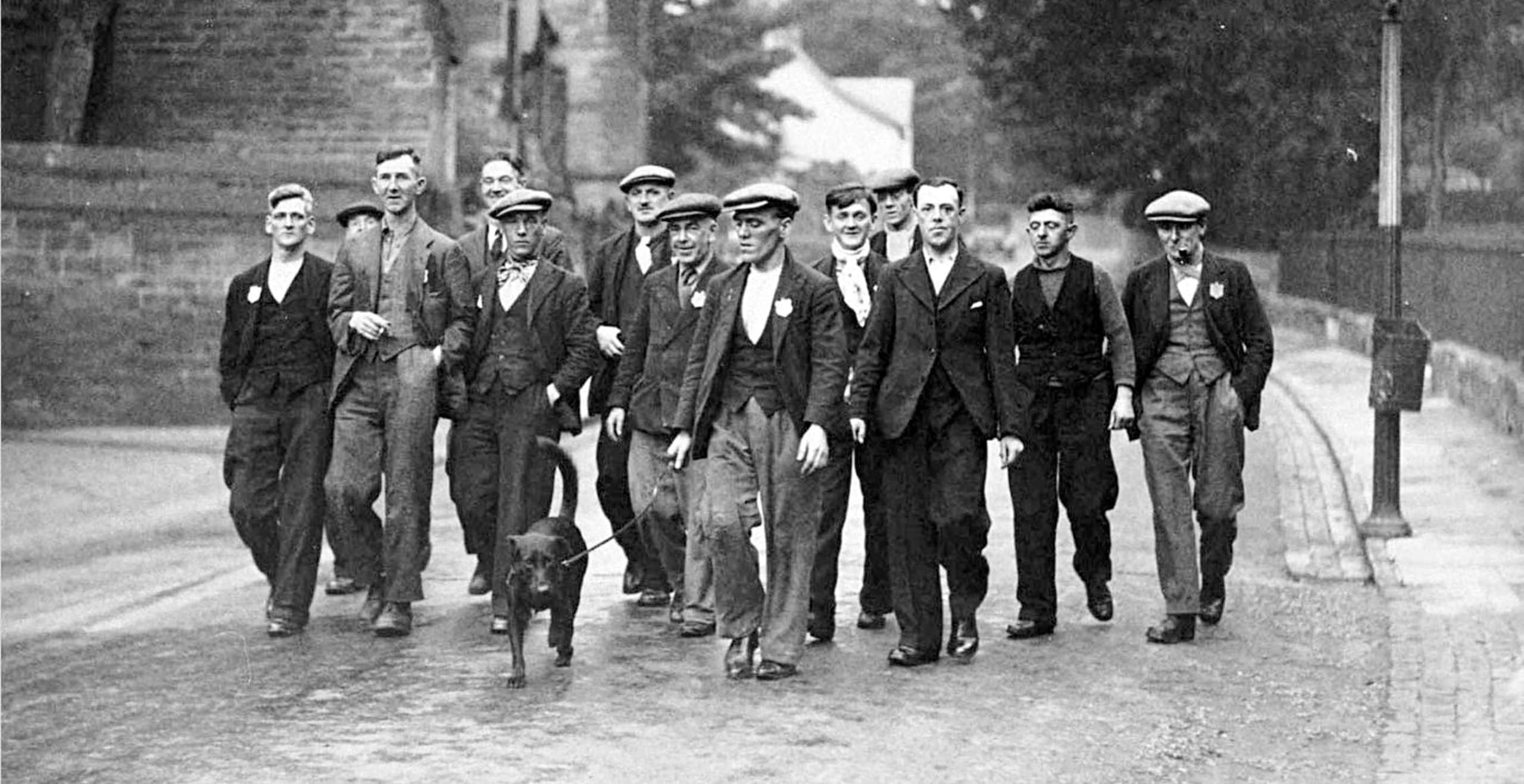

Her desire for action was further stirred after becoming friendly with Louise Martindale, a customer at the shop and activist for women’s rights, who took Margaret under her wing. In 1894, Margaret left Brighton and went to live with her brother in London – working, again, in a shop. By now, she had had become an active Union member and shortly after the move was elected to the Shop Assistants Union District Council.

In 1896, the Women’s Industrial Council asked Margaret to investigate the pay and conditions of shop workers. Her subsequent report and elevation to Assistant Secretary of her Union meant that by the age of 25, her political potential was being noticed in wider circles. Within a few years, Margaret was recognised as the leading authority on shop workers – constantly fighting to improve their rights and reporting her findings to Parliamentary Committees. Her desire to gain equality for women would continue throughout her life.

The first decade of the 20th century saw Margaret co-found the first trade union for women, the National federation of Women Workers, and play an active role in the Women’s Labour League. By 1910, she was working as an advisor to the Liberal government – helping to influence the Health Insurance Bill, giving improved maternity benefits to mothers. This, along with her campaigning efforts for improvements in child welfare; a reduction in infant mortality rates and minimum wage laws cemented her activist reputation and paved the way for her subsequent political career. Her ideals owed much to a prominent role within the Women’s Co-operative Guild, leading to lifelong links with the Co-operative movement.

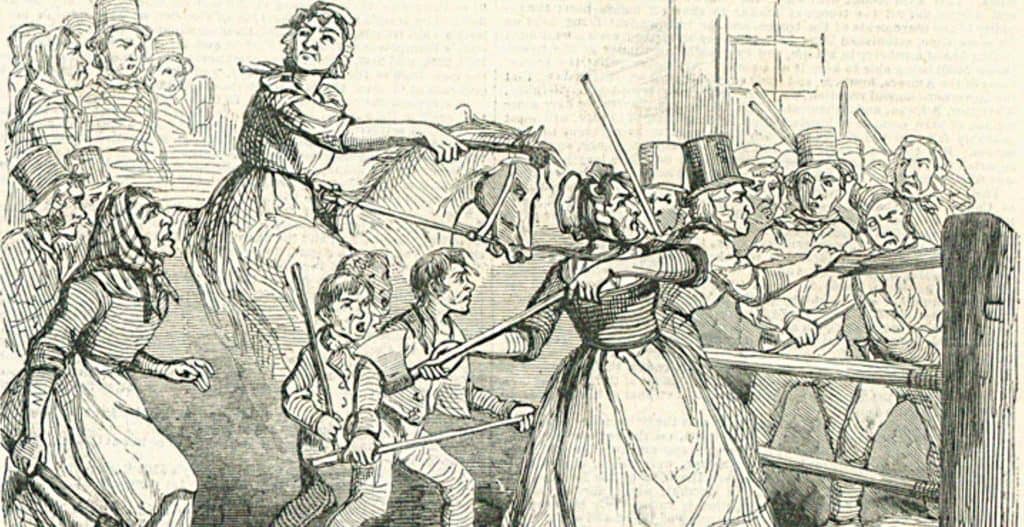

Prior to the First World War, Margaret was chairperson of the Adult Suffrage Society – working in another area to further gender equality. Her efforts to win the vote for poorer, working class women were not always popular with the more cautious aims of other suffragettes – a powerful speaker, she was not afraid to use her charm and relative youth to win over waverers at times.

Continuing her work for social equality throughout the war years and beyond, Margaret was approached to stand as a Labour candidate for Northampton. Victory at her third attempt, in the 1923 election, meant that she became one of the first female MP’s – reward for her efforts in helping to gain further rights for women, although votes for all adult women would take a little longer to achieve.

History was made in early 1924, when she was appointed as Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Labour – the first woman ever to become a government minister. This was to be short-lived, however, as Margaret lost her seat in the following year’s general election – regaining her place as an MP in the Wallsend by-election of 1926.

A greater honour was to follow. In 1929, she was made Minister of Labour in the new government – the first time that a woman had been made a British Cabinet minister. She soon found out that political realities could conflict with personal ideals – her support of a government policy to cut unemployment benefit for some married women during the Depression proving particularly unpopular with Labour voters. In the face of rising unemployment, this was a difficult time to be Minister of Labour and Margaret was placed in an almost impossible position. Losing her seat in the 1931 election meant that Margaret’s parliamentary career was over. Despite attempts at a come back, she played no active part in politics again. Suffering from ill health in later life, she died, in Surrey, in 1953.

The reforming efforts of the working class girl from Chard, who started work as a lowly shop assistant, played a huge part in advancing women’s rights in the first part of the last century. She fought for and succeeded in gaining improvements in working conditions; living standards; universal suffrage and overall gender equality. Her pictures in the National Portrait Gallery suggest a strong, determined character – driven to succeed in her life’s work.

Bondfield Way, a small 1940’s-built estate on the outskirts of Chard, and the granting of the freedom of the town are further acknowledgements of the town’s pride in Margaret’s achievements. The last words of the Guildhall’s blue plaque, however, provide the most fitting epitaph:

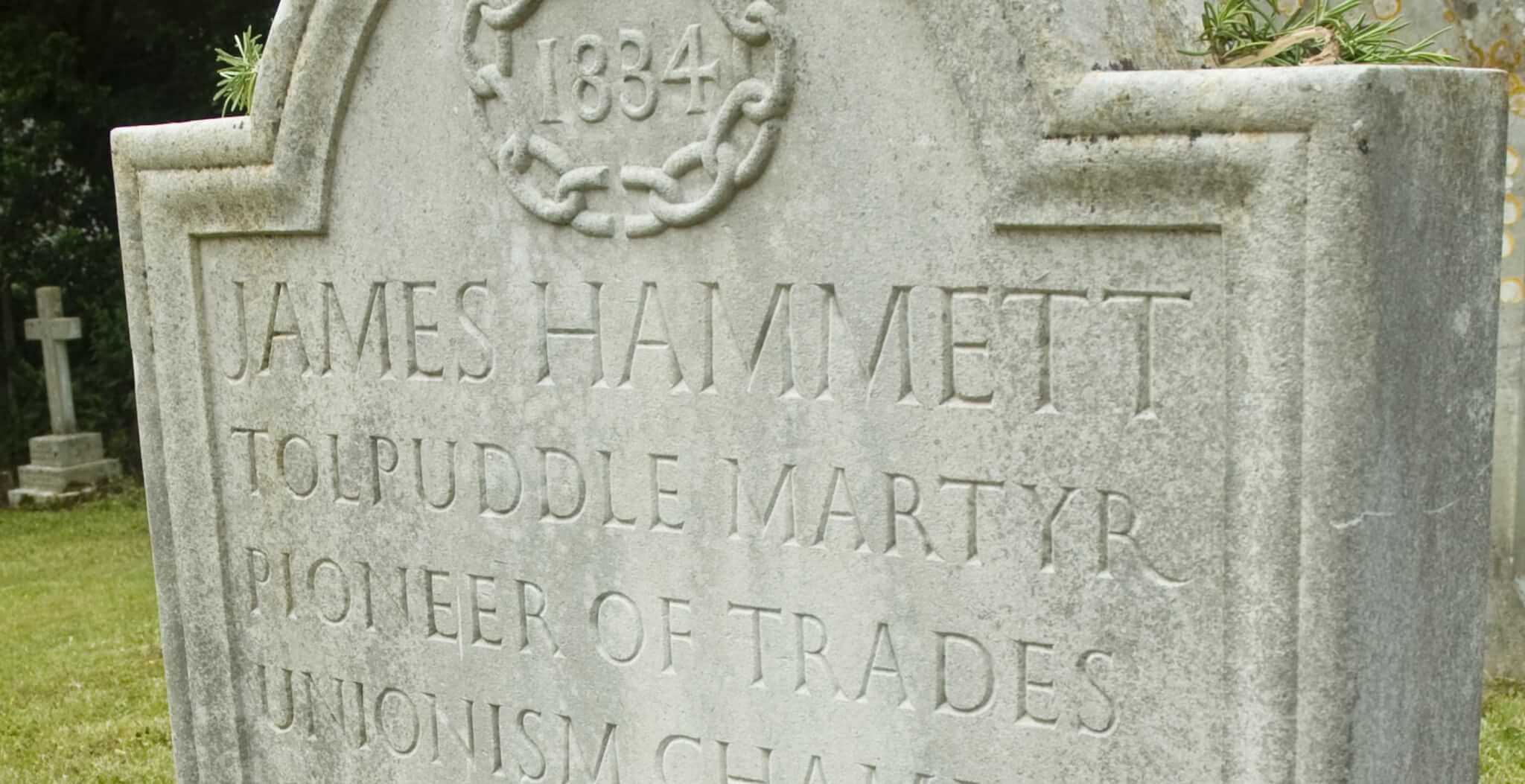

‘Shop worker, Christian, Socialist, Trades Unionist, she devoted her life to improving the lot of the downtrodden’.

Published: 4th March 2015.