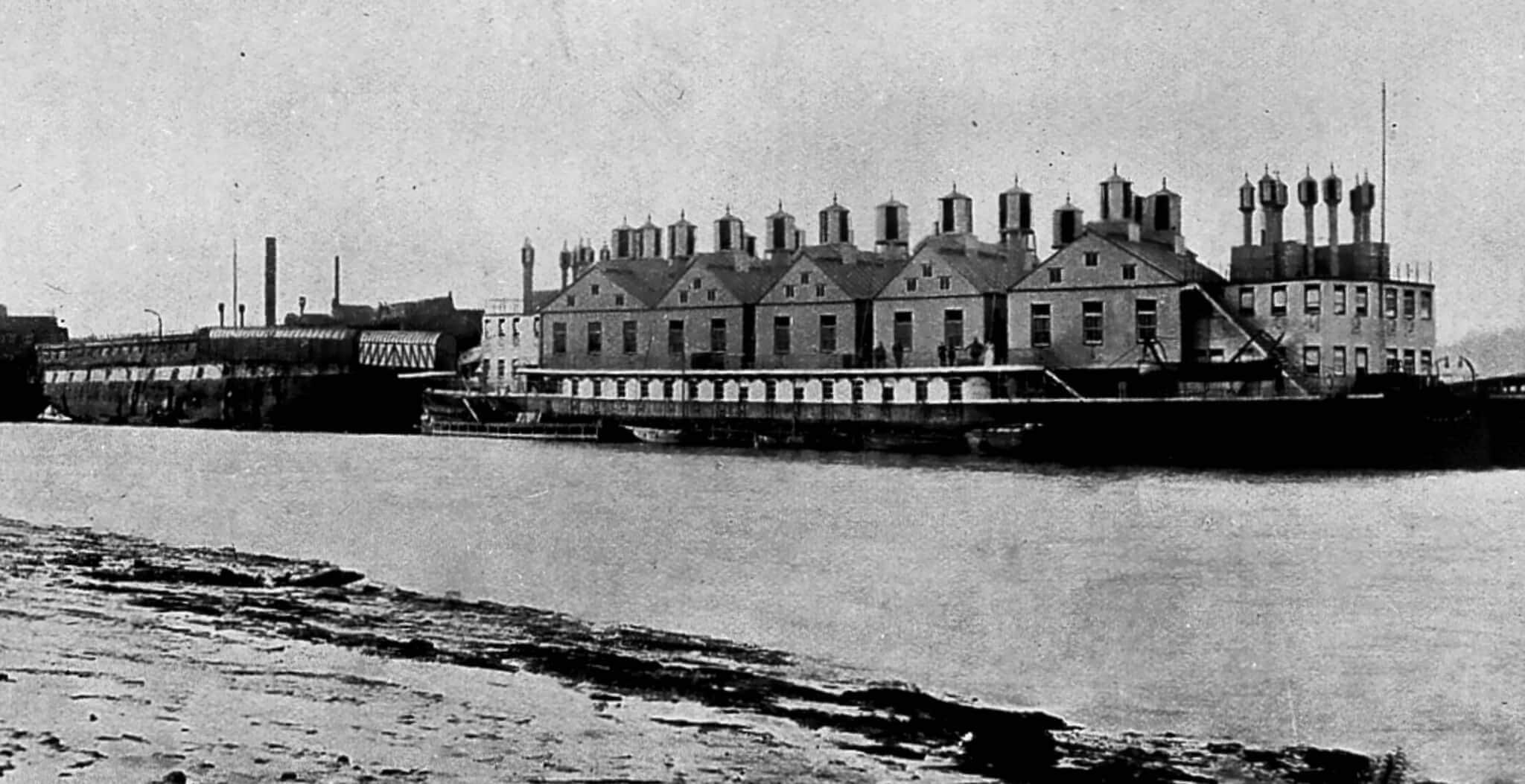

For centuries, there was no prison service in England. Prisons were not only kept by the Royal household and its retainers, but also by the Church, organisations of local businessmen, and also aristocrats and other individuals. For those with sufficient wealth and influence both inside and outside the prison walls, prisons were essentially money-making rackets. This was true of the Marshalsea Prison, one of London’s jails of ill repute, located in Southwark on the south bank of the Thames.

Southwark had achieved notoriety by Shakespeare’s day. The location of the palace of the Bishops of Winchester, it was also London’s pleasure zone, with numerous brothels, inns, taverns, and entertainments, including vicious animal shows such as bear and bull baiting.

Playhouses too, including the original Globe Theatre of the company of players that included Shakespeare. All these activities produced wealth that could be diverted into the coffers of the Bishop, and for centuries the prostitutes of Southwark provided such a fat income that they were known as Winchester geese. The bishop’s palace even had its own jail, the famous Clink.

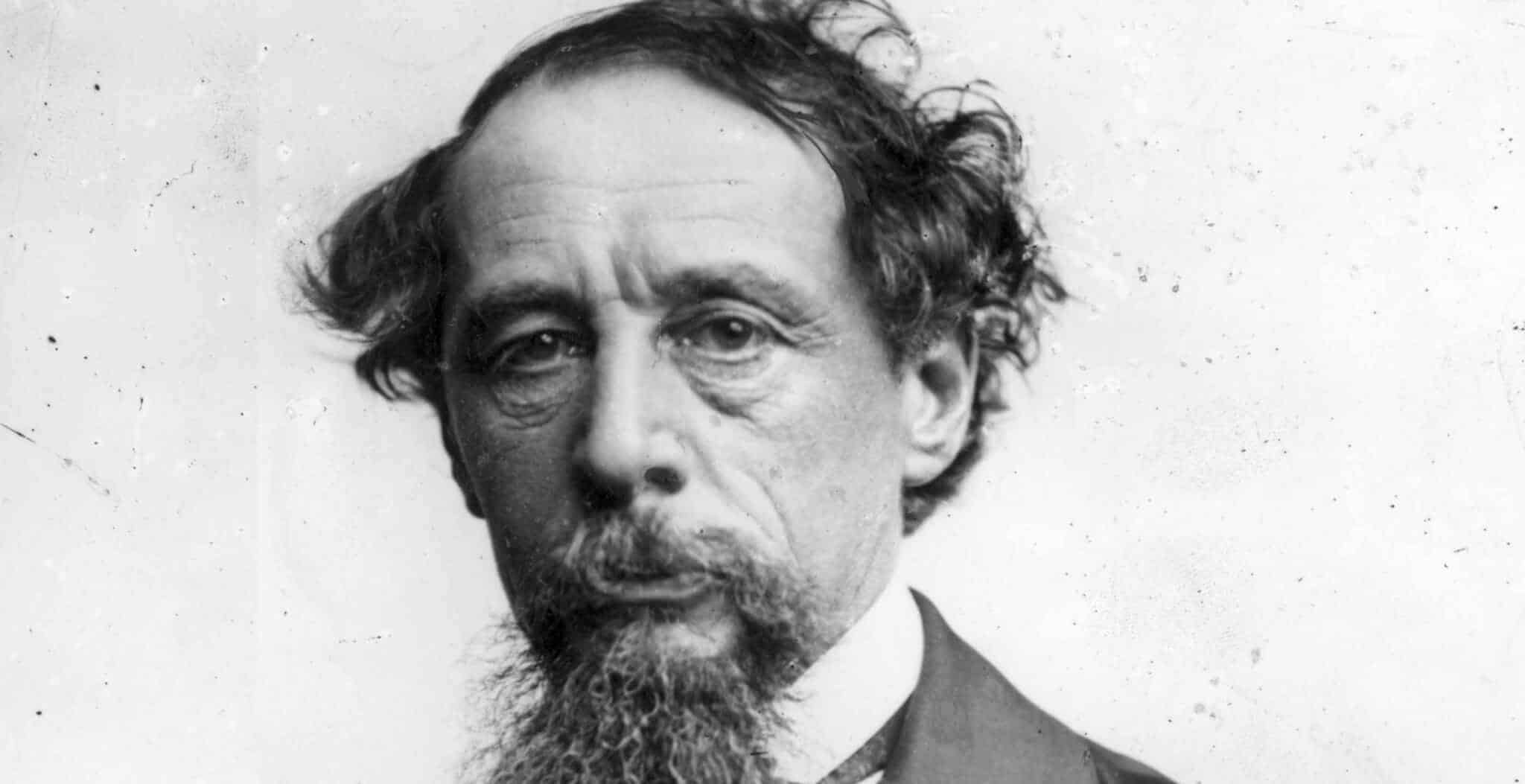

The Marshalsea Prison was a feature of the Southwark landscape for centuries. The first prison was built in Borough Street in 1373 and this building endured until 1811. The Marshalsea Prison that replaced it from 1812 until 1842 clearly had a much shorter life span, but an equally menacing reputation. Through the gates of the Marshalsea came pirates and smugglers, seditious writers and debtors. It was one of five prisons in Southwark, a relatively large number for a single area of London, and arguably an important contributor to Southwark’s dubious and booming economy.

The name of the prison reflects its royal origins. The role and office of the Marshal was an important one, deriving from a German word meaning farrier (marh meaning horse, and scalc, servant). Although being a “horse-servant” doesn’t sound very impressive, the work of a farrier in medieval times was a prestigious and almost magical pursuit, given society’s dependence on horses. Their work covered not only foot care and shoeing but also equine health care and management.

The term Marshal came to have prestige. There were many marshals working in households throughout Britain, but none was more important than the King’s Marshal, or the Marshal of the King’s Horses, a role created by Henry III. The term King’s Marshal was connected not only to the royal family, but also to its law court. Thus, the Marshalsea jurisdiction was originally known as the Marshalsea Court, reflecting its status as the legal court of the royal household. It was responsible for the behaviour of members of the royal household living within a certain distance of the king. It was also an ambulatory court, meaning it moved with the king as he progressed around the country. Inevitably this meant that it began to deal with cases not directly linked to the royals and their household. In time, the majority of prisoners in the Marshalsea Prison were there for debt.

Superficially, The King’s Knight Marshal remained responsible for the Marshalsea Prison over the centuries. In practice, this official frequently hired someone to run the prison as its governor. This individual would often lease it out to another person for the day-to-day management of the prison and its inmates. These were often men whose principal interest was profit, not the condition of the prisoners. One such, William Acton, paid for a seven-year lease on the prison and also for the rights to collect the rents from the private rooms, and sell food and other essentials to the inmates. These lease-holders would often lease out their privileges to other prisoners in the jail, such as the right to a shop selling goods to other inmates.

The Marshalsea created its own community, with a tap room selling beer, a tavern, shops, a steakhouse, and even a barber. Food, drink, and other items could all be brought in by those who could afford it. Prisons were bitterly cold in winter, and coal was essential for those in the master’s side if they wanted warmth.

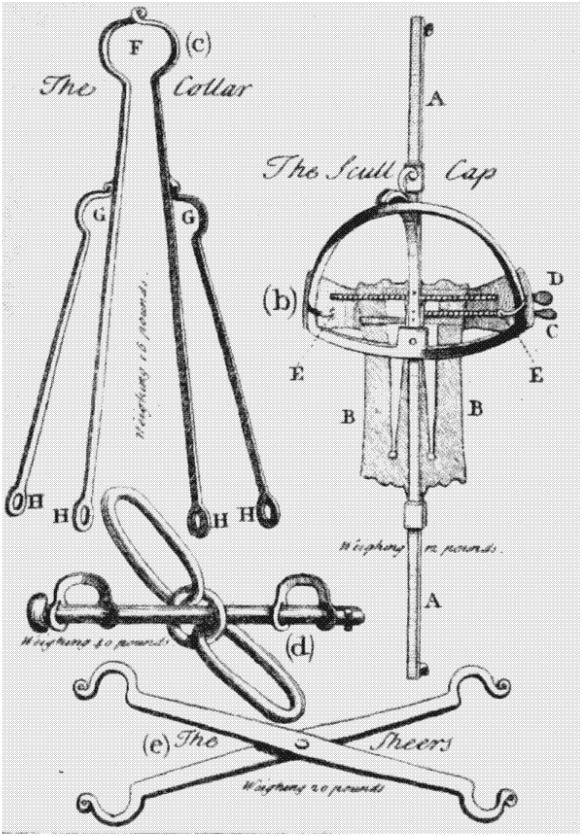

Under management that was either indifferent to the welfare of the prisoners, or ruthless in its endeavour to make money out of them, it is scarcely surprising that many died of illness or even starvation. William Acton was eventually accused of murdering three of the inmates of the Marshalsea and stood trial. Despite eye-witness accounts of him beating and stamping on the prisoners, and leaving them in thumbscrews and the skullcap (a head vice) for days, thrown into the confines of the hole, he was acquitted.

No one could survive in prison without money. Everything had to be paid for. No sooner had the prisoners arrived than they were asked by the jailor or a prison committee made up of inmates to provide “garnish”, as if it were an entry fee into the exclusive club of the prison! In some ways it was. This fee could provide access to some of the essentials of life, including entry to an area for cooking, and the chance to purchase candles and other comforts.

In the days when prisoners were shackled, they could pay for “easement”, that is to have their chains replaced with lighter ones, or removed. The master’s side was for those who could afford to pay for better rooms, who formed the jail’s elite, while those who could not afford them were placed in the common side, among all classes of prisoner. Here were the most destitute, at greater risk of sickness, starvation, and death. They were crowded into the nine ward rooms with shared boards for beds if they were lucky.

There was a separate side, or ward, for women prisoners, which probably provided slightly more safety, but in practice women often shared the conditions of their partners, whether in the common side or the master’s side. Sex was simply another of the commodities available to the wealthier prisoners. The governors did not concern themselves with what the inmates were doing, how they kept themselves or where they went, as long as they could reap any benefits. Nowhere did money talk more influentially than inside the walls of prisons like the Marshalsea.

A strange mix of people passed through the gates of the Marshalsea. In the seventeenth century, as well as smugglers and pirates, well-known writers such as Ben Jonson and the poet George Wither were incarcerated here for their biting satires on public life. Those viewed as radicals, heretics, and political agitators were usually sent here too, but in the eighteenth century debtors made up more than half the prison population.

By 1773 debtors could be held here for debts as low as 40 shillings. In theory debtors were kept separately from the more dangerous criminals, but in practice the prison was a very open one. Families and messengers of the prisoners came and went much as they pleased, at least from the private accommodation. At night the prison gates were locked, the doors were barred, and any outside visitor who had failed to meet the curfew was locked inside for the night.

Attempts were made to reform prisons as early as the seventeenth century. Then in 1728 Thomas Bambridge, warden of the Fleet Prison, sent a well-connected debtor, Robert Castell, to a sponging house because of a complex series of borrowing and bonds that left him heavily in debt to Bambridge. These were places where the prisoners were packed in and exploited until their last drops were squeezed out of them – hence sponging house. Castell, who was a talented architect, died of smallpox here.

Castell’s acquaintance, a Tory MP named James Oglethorpe, began to raise questions about the condition of prisoners, and a formal complaint was submitted to the Mayor of London. This led to the setting up of the Gaols Committee in 1729, at which the whole horror of the condition of the prisoners and their inhuman treatment was revealed. Prisoners were not only bullied, menaced, and beaten, but tortured with thumbscrews and vices that squeezed the head, as well as starved. People were now aware of the shocking conditions, but prison reform moved slowly.

By the time prison reformer John Howard was making a survey of the jails for his 1777 publication “The State of the Prisons in England and Wales” little appears to have changed in some places. Jails were filthy, and although instruments of torture were a thing of the past, people had continued to be shackled and confined in tiny spaces with no heat or comfort. Several accounts written by people who were confined within the Marshalsea confirm the parliamentary accounts. Reformers continued to visit the new Marshalsea Prison, completed in 1812.

Curiously, the Marshalsea Prison could also provide a kind of refuge for those prisoners who understood how to work the situation to their advantage, and who could afford it. Privileged inmates and their families could go out to work, and in this way provide sufficient income for survival and in some cases, comfort. They were able to survive in the Marshalsea, as long as they had some money, without their creditors falling on them like a pack of wolves.

As a character in the novel “Little Dorritt” summarised it: “We are quiet here; we don’t get badgered here; there’s no knocker, sir, to be hammered at by creditors and bring a man’s heart into his mouth. Nobody comes here to ask if a man’s at home, and to say he’ll stand on the door mat till he is. Nobody writes threatening letters about money to this place. It’s freedom, sir, it’s freedom! … I don’t know that I have ever pursued it under such quiet circumstances as here … we have got to the bottom, we can’t fall, and what have we found? Peace. That’s the word for it. Peace.”

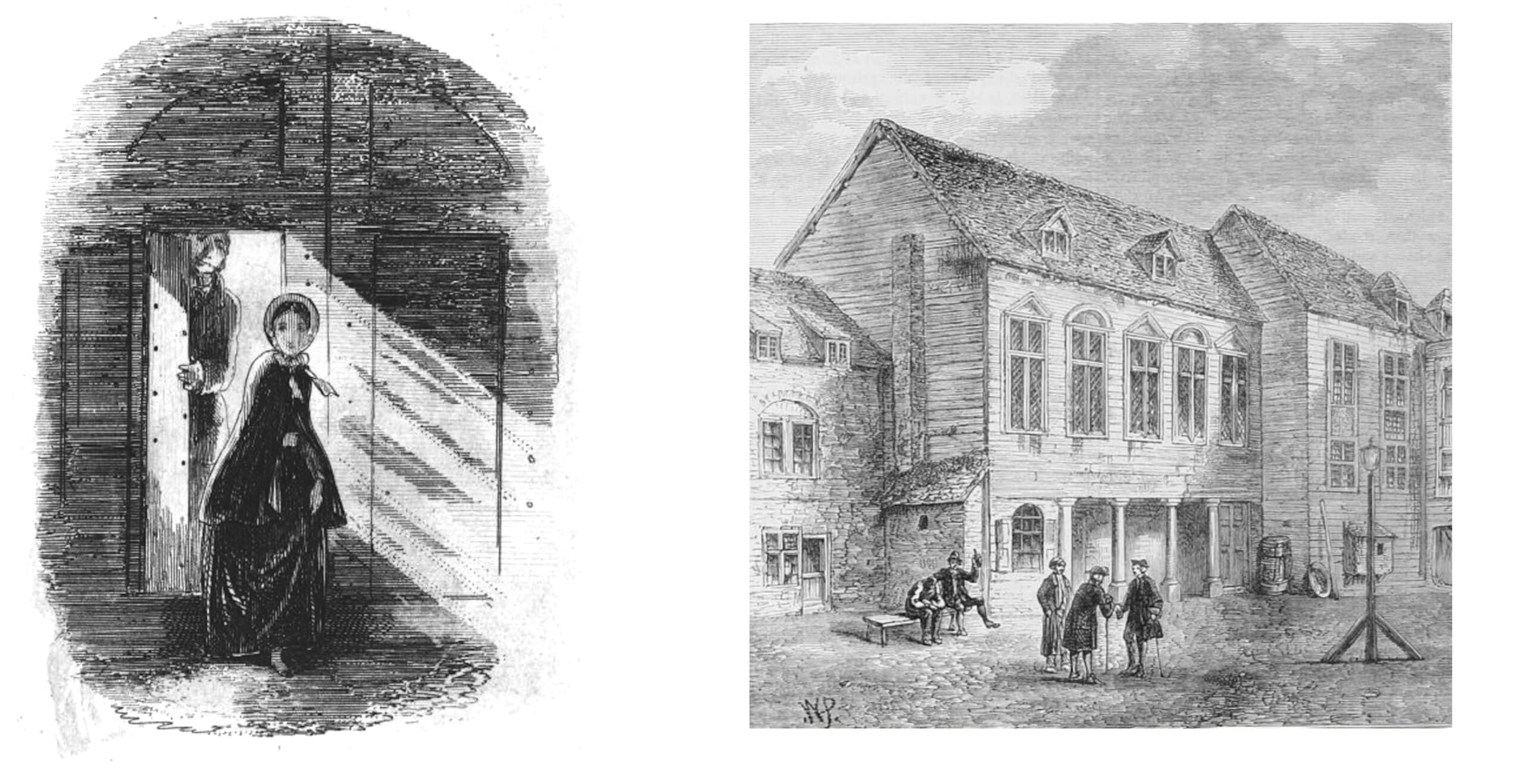

However, few could ever afford to pay off the original debt and the higher the debt, the longer they were likely to stay inside the Marshalsea. The conditions that Dickens described in “Little Dorritt” were those he knew well, since his own father had been imprisoned for debt there. This meant Dickens as a child had been forced to work in a factory that made boot blacking for polishing shoes and boots. In the novel, Amy Dorritt, who was born in the Marshalsea after her father was taken there for debt, goes out to work as a seamstress to earn enough money to keep her father in the relative comfort of the master’s side.

Amy’s father is so respected that he earns the title “Father of the Marshalsea”. The prison is described as being like a college (and the buildings appear to have been constructed to give an impression of an Oxford college), and so the inmates are called “collegians”. Amy’s father, her feckless brother and society-loving sister are able to maintain some pretence of importance due to Amy’s hard, hidden work behind the scenes.

The Dorritt family is rescued from poverty by a sudden stroke of fortune. As the family progresses in society and the world beyond the prison, even touring abroad, Amy Dorritt muses that wealth is as much a trap as poverty: “It appeared on the whole, to Little Dorrit herself, that this same society in which they lived, greatly resembled a superior sort of Marshalsea. Numbers of people seemed to come abroad, pretty much as people had come into the prison; through debt, through idleness, relationship, curiosity, and general unfitness for getting on at home. They were brought into these foreign towns in the custody of couriers and local followers, just as the debtors had been brought into the prison.”

Wealth and freedom do not necessarily bring happiness, Amy concludes, noting that the tourists were restless and dissatisfied like the prison inmates, and the attractions they had come to see seldom pleased them, leaving them prowling about “much in the old, dreary, prison-yard manner” and paying “high for poor accommodation”, while “[disparaging] a place while they pretended to like it: which was exactly the Marshalsea custom”. Whether in debt or not, it is clear to Amy that wealth creates shackles.

The Marshalsea was finally closed in 1842 and the inmates dispersed to other places, including the Bethlem Hospital and the Queen’s Prison (formerly the King’s Bench Prison), though people could still be imprisoned for debt until 1869. In 1849 the ancient Court of the Marshalsea of the Household of the Kings of England was abolished. Dickens returned to his old haunt in 1857, noting that the main block, by then renamed Marshalsea Place and the wall still remained. The prison was finally demolished in the 1870s, apart from the southern wall, which stands to this day. The long life of the Marshalsea Prison is commemorated (or its final disappearance celebrated) with a plaque on this wall.

Dr Miriam Bibby FSA Scot FRHistS is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published: 14th June 2024