The year was 1888 and the location Bow in the East End of London, a place where some of the most poverty stricken in society lived and worked. The Match Girls’ Strike was industrial action taken up by the workers of the Bryant and May factory against the dangerous and unrelenting demands which endangered their health with very little remuneration.

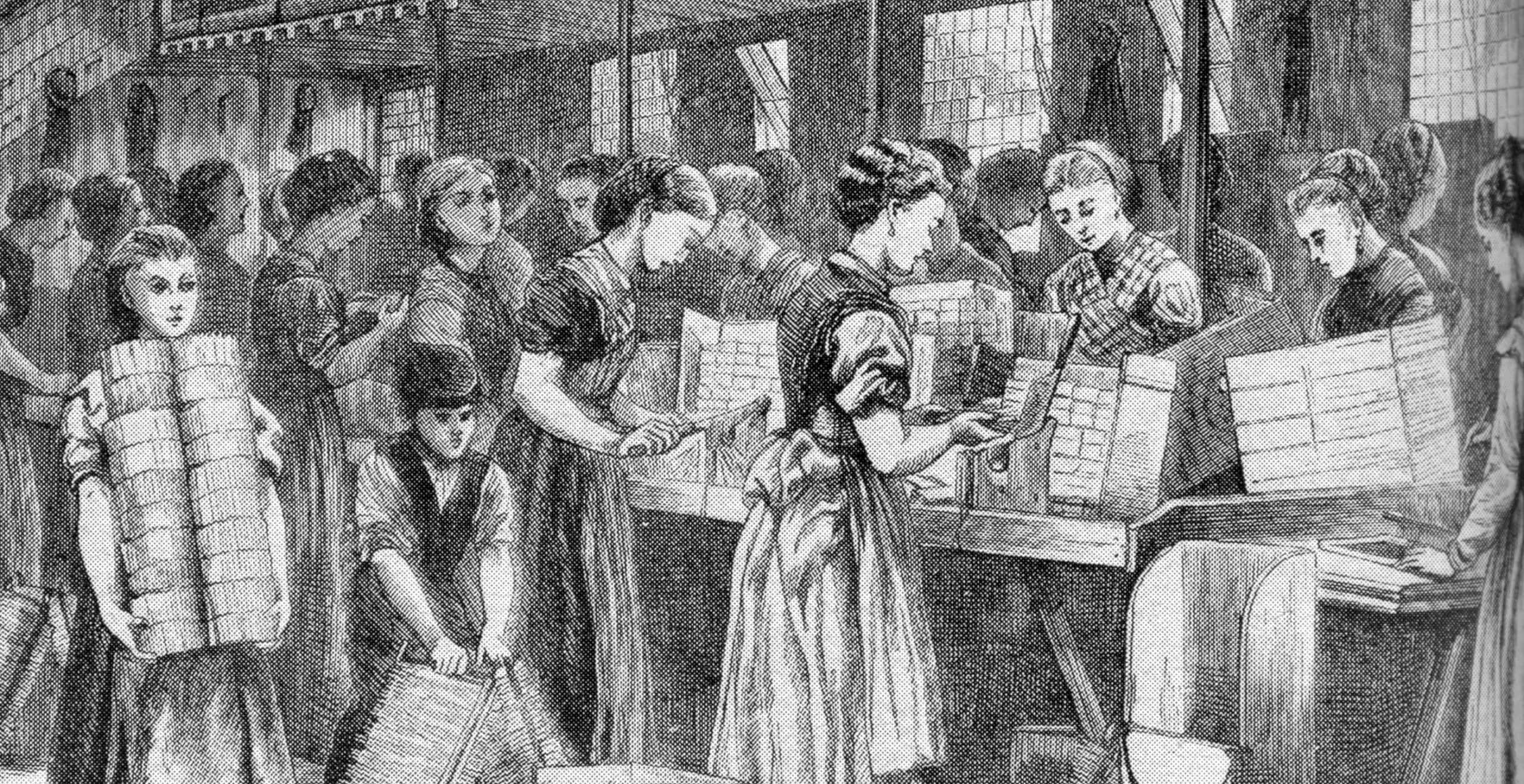

In London’s East End, women and young girls from the surrounding area would turn up at 6:30 in the morning to start a long fourteen hour shift of perilously dangerous and gruelling work with a virtually non-existent financial recognition at the end of the day.

With many of the girls starting their life at the factory at thirteen years of age, the demanding physicality of the job took its toll.

The match workers would be required to stand for their work all day and with only two scheduled breaks, any unscheduled toilet break taken would be deducted from their meagre wages. Furthermore, whilst the pittance earned by each worker was barely enough to live on, the company continued to thrive financially with dividends of 20% or more given to its shareholders.

The factory was also inclined to issue out a number of fines as a result of misdemeanours including having an untidy work station or talking, which would see the low wages of the staff cut even more dramatically. Despite many of the girls being forced to work bare-footed as they could not afford shoes, in some cases having dirty feet was another reason for a fine, thus subjecting them to further hardship by deducting their wages even further.

The healthy profits made by the factory were unsurprising, particularly as the girls had to have their own supplies such as brushes and paint whilst also being forced to pay the boys who provided the frames for boxing up the matches.

Through this inhumane sweat shop system, the factory could navigate the restrictions imposed by the Factory Acts which was legislation created in an attempt to halt some of the more extreme industrial working conditions.

Other dramatic ramifications of such work also affected the health of these young women and girls, often with disastrous effects.

With no attention paid to health and safety, some of the instructions given included “never mind their fingers”, as the workers were forced to operate dangerous machinery.

Moreover, abuse from the foreman was a common sight in such demoralising and abusive working conditions.

One of the worst ramifications included a disease called “phossy jaw” which was an extremely painful type of bone cancer caused by the phosphorus in the match production leading to horrendous disfiguration of the face.

The production of match sticks involved dipping the sticks, made from poplar or pine wood, into a solution made up of many ingredients including phosphorus, antimony sulphide and potassium chlorate. Within this mixture, there were variations in the percentage of white phosphorus however the use of it in production would prove to be extremely dangerous.

It was only in the 1840’s that the discovery of red phosphorus, which could be used on the striking surface of the box, made the use of white phosphorus in the matches no longer necessary.

Nevertheless, the use of it in the Bryant and May factory in London was enough to cause widespread problems. When someone inhaled phosphorus, common symptoms such as toothache would be reported however this would lead to the development of something much more sinister. Eventually as a result of the heated phosphorus being inhaled, the jaw bone would begin to suffer a necrosis and essentially the bone would start to die.

Fully aware of the impact of “phossy jaw”, the company chose to deal with the problem by giving the instruction of tooth removal as soon as anyone complained of an ache and if anyone dared refuse, they would be fired.

Bryant and May was one of twenty-five match factories in the country, of which only two did not use white phosphorus in their production technique.

With little desire to change and compromise on profit margins, Bryant and May continued to employ thousands of women and girls in its production line, many of Irish descent and from the poor surrounding area. The matchmaking business was booming and the market for it continued to grow.

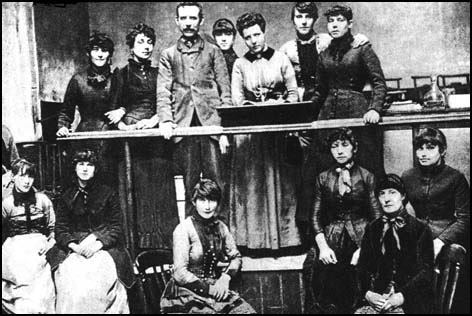

Meanwhile, after growing discontent over the poor working conditions, the final straw came in July 1888 when one female worker was wrongfully dismissed. This was the result of a newspaper article which exposed the brutal conditions of the factory, which prompted the management to force signatures from its workers refuting the claims. Unfortunately for the bosses, many workers had had enough and with the refusal to sign, a worker was dismissed triggering off outrage and the subsequent strike that followed.

The article had been prompted by activists Annie Besant and Herbert Burrows who were key figures in organising the industrial action.

It was Burrows who had first made contact with the workers in the factory and later Besant met with many of the young women and heard their appalling stories. Prompted by this visit, she soon published an exposé where she gave details of the working conditions, comparing it to a “prison-house” and depicting the girls as “white wage slaves”.

Such an article would prove to be a bold move as the matchstick industry was very powerful at the time and had never been successfully challenged before now.

The factory was understandably outraged to learn of this article which gave them such bad press and in the days that followed, made the decision to force the girls into a full-scale denial.

Unfortunately for the company bosses, they had completely misread the growing sentiments and instead of oppressing the women, it emboldened them to down tools and travel to the offices of the newspaper in Fleet Street.

In July 1888, after the unfair dismissal, many more match girls came out in support, quickly igniting the walkout into a full-scale strike of around 1500 workers.

Besant and Burrows proved crucial in organising the campaign which led the women through the streets whilst setting out their demands for an increase in pay and better working conditions.

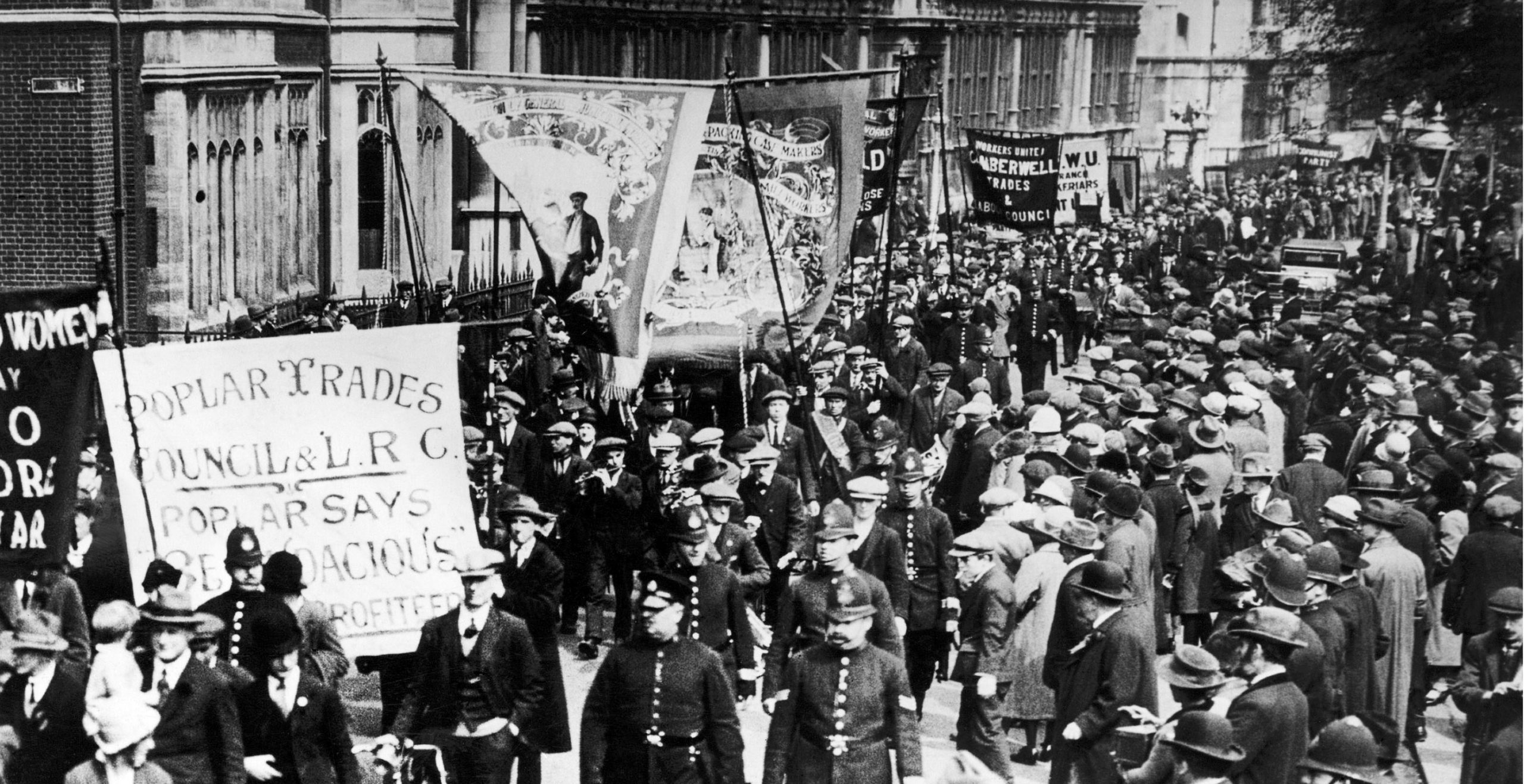

Such a display of defiance was met with great public sympathy as those who saw them pass by cheered and offered their support. Moreover, an appeal fund set up by Besant received a great many donations including from powerful bodies such as the London Trades Council.

With the support triggering public debate, the management were keen to play down the reports, claiming it was “twaddle” propagated by socialists like Mrs Besant.

Nevertheless, the girls spread their message defiantly, including a visit to Parliament where the contrast of their poverty against the wealth of Westminster was a confronting sight for many.

Meanwhile, the factory management wanted to mitigate their bad publicity as soon as possible and with the public very much on the side of the women, the bosses were forced to compromise just weeks later, offering improvements in both pay and conditions, most notably including the abolition of their stringent fining practices.

It was a victory not seen before against the powerful industrial lobbyists and a sign of changing times as the public mood had empathised with the plight of working women.

Another effect of the strike was a new match factory in the Bow area set up in 1891 by the Salvation Army offering better wages and conditions and no more white phosphorus in production. Sadly, the extra costs incurred by changing many of the processes and the abolition of child labour resulted in the failure of the business.

Unfortunately, it would take over a decade for the Bryant and May factory to stop using phosphorus in its production despite the changes that were imposed by the industrial action.

By 1908, after years of public awareness of the disastrous health impact of white phosphorus, the House of Commons finally passed an act prohibiting its use in matches.

Moreover, a notable effect of the strike was the creation of a union for the women to join which was extremely rare as female workers did not tend to be unionised even into the next century.

The match girl strike had provided an impetus for other working class labour activists to set up unskilled worker unions in a wave that became known as “New Unionism”.

The 1888 match girl strike had paved the way for important changes in the industrial setting but more still needed to be done. Its most tangible impact was perhaps the growing public awareness about the conditions, lives and health of some of the poorest in society whose neighbourhoods were a far cry from those of the decision makers in Westminster.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: April 19, 2021.