For all those working towards the common goal of women’s suffrage, the year 1928 was a momentous and celebratory time when all British women aged over 21 were finally granted the right to vote in elections.

Those who had been the champions of this cause however, did not always pursue their objectives in the same way and were split in their approach, leading to two campaigns lead by the suffragists and the suffragettes.

With the suffragettes gaining notoriety for their actions, the group strongly advocated for direct action and a militaristic approach which did not always win favour amongst the political class who held the decision-making veto.

On the other hand, the suffragists were those campaigners who believed in pursuing the same goal of female suffrage through peaceful and legal channels. The woman at the helm of this movement was Millicent Fawcett, a feminist and writer, who dedicated her life to the fight for female enfranchisement.

Her story began in Suffolk. Born into a privileged family and one of ten children, Millicent’s father was a businessman and wealthy merchant. Young Millicent and her siblings would benefit from their parents’ very liberal approach and unorthodox attitudes towards politics and gender roles, enabling the children to see beyond the social barriers of the day.

All ten children would be encouraged to think freely about politics and social issues, not bound by the patriarchal and institutionalised restrictions which pervaded life in Britain at this time.

The unconventional upbringing of their children would produce great results, as many of them would grow up and achieve great success in their respective fields. One of Millicent’s siblings, Elizabeth, would go on to become one of the first female doctors whilst another, Agnes was the first female interior designer and businesswoman. Meanwhile, with her family’s attitudes and aspirations holding her in good stead, Millicent would engage actively in the struggle for female emancipation and the recognition of women’s rights.

Her first foray into the world of female suffrage came when she was still very young when she was introduced by her sister Elizabeth to a campaigner and feminist called Emily Davies.

Now in education in London at a private boarding school, her siblings would prove instrumental in exposing her to a new world of discussion groups and likeminded individuals, leading her to attend a lecture by the philosopher, economist and MP John Stuart Mill.

In time, her interests would continue to grow thanks to the positive influence of her siblings and others such as friend Emily Davies, who, along with Millicent, would lend their support to the Kensington Society, a women’s group where members could campaign about pertinent issues such as education, enfranchisement and property ownership.

Meanwhile, in this new social setting based in London, Millicent met Henry Fawcett, a Liberal Member of Parliament who had been long dedicated to the cause of female suffrage. After initially expressing interesting in marrying her sister Elizabeth, he turned his attention to Millicent, as her sister was determined at the time to pursue her career in medicine.

In April 1867 Millicent married Henry; this was a happy union full of intellectual rigour, support and understanding for each other. Her role in the relationship was vital as Henry had sadly lost his sight when he was twenty-five in a tragic shooting accident. He would rely on Millicent, who would serve as his secretary as well as helping to run two households in both London and Cambridge.

Despite his disability, her husband would prove to be a success, able to enter Lincoln’s Inn before turning his attention to academia. He became a notable authority in the field of economics before being elected as Rector of Glasgow University.

Whilst he turned his attentions to politics, it was the female suffrage campaign which would draw himself and Millicent closer together. They went on to have one child, Philippa, who was encouraged to be ambitious and studious, eventually going on to obtain top marks in the Cambridge Mathematical Tripos exam, the first woman to do so.

Settled into family life, she would also support her husband’s political career and would speak at public meetings in his constituency. Furthermore she also turned her attention at this time to developing a writing career, publishing essays alongside her husband.

By 1875, she co-founded the newly built Newnham College, an all-female college at Cambridge University.

With her career blossoming, sadly her personal life would end up consuming much of her time. Her husband died in 1884 from pleurisy, leaving Millicent and their daughter Philippa alone. She ended up moving in with her sister Agnes whom she had been helping to raise their four cousins who had sadly been orphaned.

After taking a much needed break from public life, Millicent resumed her work and joined the Women’s Local Government Society as well as the Liberal Unionist Party.

Whilst Millicent continued to build a successful career for herself, as well as becoming involved in campaign groups, her real breakthrough occurred when she became leader of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, the NUWSS.

After dedicating herself to the cause since her first speech in 1869 advocating votes for women, she had found her true calling and settled into the role of President of the NUWSS, serving from 1907 until 1919.

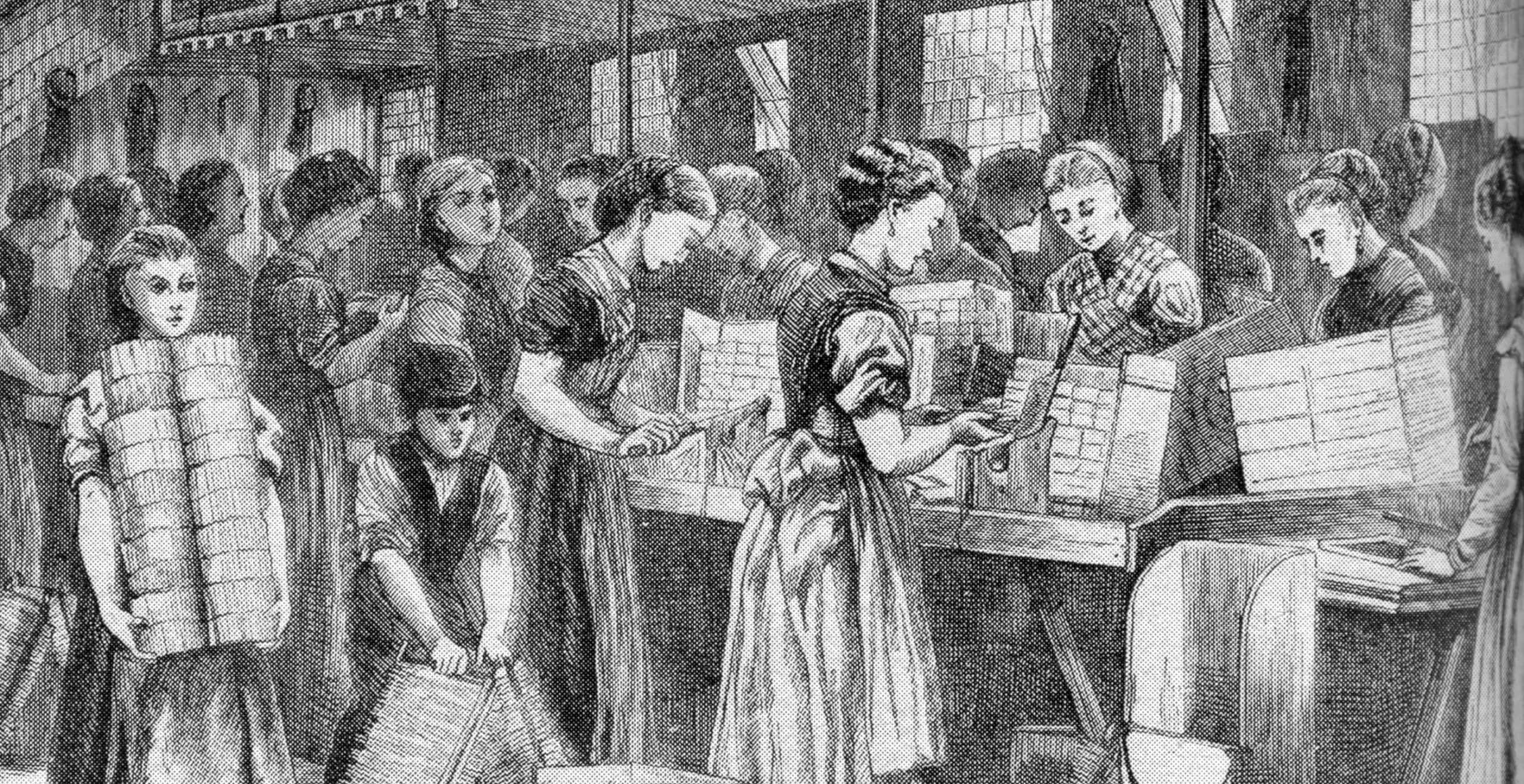

The nature of the organisation centred on peaceful, non-violent and constitutional campaigns which would raise the profile of the group and the message through traditional methods such as leaflets, public speeches and petitions.

Her approach was cautious, believing that a more conservative stance would in the end bring about the desired result through legal and constitutional means. In direct opposition to this were the suffragettes and the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), led by Emmeline Pankhurst whose militancy would lead to force feeding, arson and most famously the death of Emily Davison at the Epsom Derby.

Millicent believed that despite the great level of publicity which the suffragettes received, their actions did very little for the constitutional changes which both groups were striving to achieve. Instead, their militancy would simply alienate MPs and members of the public who might otherwise have supported the cause.

Therefore, the NUWSS kept to its slogan of “Law-abiding suffragists” and garnered a healthy base of support, so much so that in 1905 the society consisted of around 50,000 members, compared to the militant WSPU’s 2000 members eight years later.

In 1914 the NUWSS’s numbers had grown further to almost 55,000 members under the leadership of Millicent Fawcett. They did however recognise that their support base was made up predominantly from women of an upper and middle class background and wanted to rectify this by enticing support from women from all walks of life.

In a campaign of pamphlets and propaganda, the NUWSS did gain followers from working class backgrounds as they attempted to make the case for votes being needed from everyone, whatever their role in society.

For some however, the peaceful and unassuming tactics of the suffragists were failing to produce the desired results quickly enough and this lead some to move towards the more public image aware suffragettes with the motto, “Deeds not Words”.

Despite the parallel campaign efforts of both groups, the outbreak of the First World War led both parties to cease their current activities and focus on the war effort.

For Millicent Fawcett this included providing hospital services in training camps whilst also diverting their raised funds to the government as did the WSPU movement. The NUWSS operated during the war with the principle of “Let us prove ourselves worthy of citizenship whether our claim is recognised or not”.

Whilst some of the pacifist tendencies of the NUWSS proved difficult to navigate in the setting of war, Fawcett managed to steer the group on a course of campaigning, highlighting the incredible contribution that women had made during the war.

By 1918, the Representation of the People Act made some headway on the path to voting equality between men and women, as the vote was extended to women over 30 with certain property requirements.

A year later, Millicent, now aged seventy-two, would retire from the presidency of the NUWSS and give way to Eleanor Rathbone.

Whilst her retirement from the organisation brought an end to a large and eventful chapter in her life, Millicent’s activities and efforts to affect change would not diminish, instead she focused on her writing and campaigning for many other causes which affected women, ranging from education, career paths to divorce rights.

In 1925 she was made a Dame of the British Empire and also served as vice-president of the League of Nations Union. In her lifetime she had remained concerned with not only the legal status and voting privileges of women, but every aspect of female life that up until now had been governed and controlled by men.

Finally in 1928 the day had come that Millicent and many others would derive so much pleasure from; the Equal Franchise Act giving all citizens over the age of twenty-one the right to vote.

In August 1929, a year after seeing this act come to pass, she died, leaving behind a substantial legacy as a campaigner, feminist and writer who strove throughout her life to make change happen.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 16th August 2023.