They were the British naval vessels that officially didn’t exist; the mystery ships of World War One. Their captains and crew needed to be masters of disguise, not only of themselves but of their vessels. To all intents and purposes the ships were scruffy little colliers, tramp steamers, fishing smacks and luggers, manned by salty old seadogs with a no-nonsense attitude to landlubbers. Behind these facades they carried 12-pounder and Maxim guns and twice the crew that a commercial craft would need. Their mission was to decoy and destroy German submarines. They were Britain’s answer to the Submarine Menace.

World War One was, in retrospect, a steampunk war fought with every kind of contemporary weapon including dashing Zoave and Hussar cavalry units, tanks, dirigibles, aeroplanes and steam trains. Horse-drawn artillery and pack mules carried on doing the tasks they had always done, alongside field telephones and wireless. This was a war in which old forms of military expertise would inevitably give way under the terrifying new technologies of high explosive shrapnel and gas warfare.

Submarines were one of the most dreaded aspects of the new weapons technology. The German High Command were far in advance of the Admiralty in adopting the submarine, and the “Submarine Menace” was the threat the German u-boats posed to British shipping. The threat was as much to the British psyche as anything else. As long as enemy submarines could appear and disappear at will, sinking commercial, merchant navy and Royal Navy ships, Britannia would no longer rule the waves. The submarines threatened the lives of civilians and sailors as well as destroying thousands of tons of vital supplies.

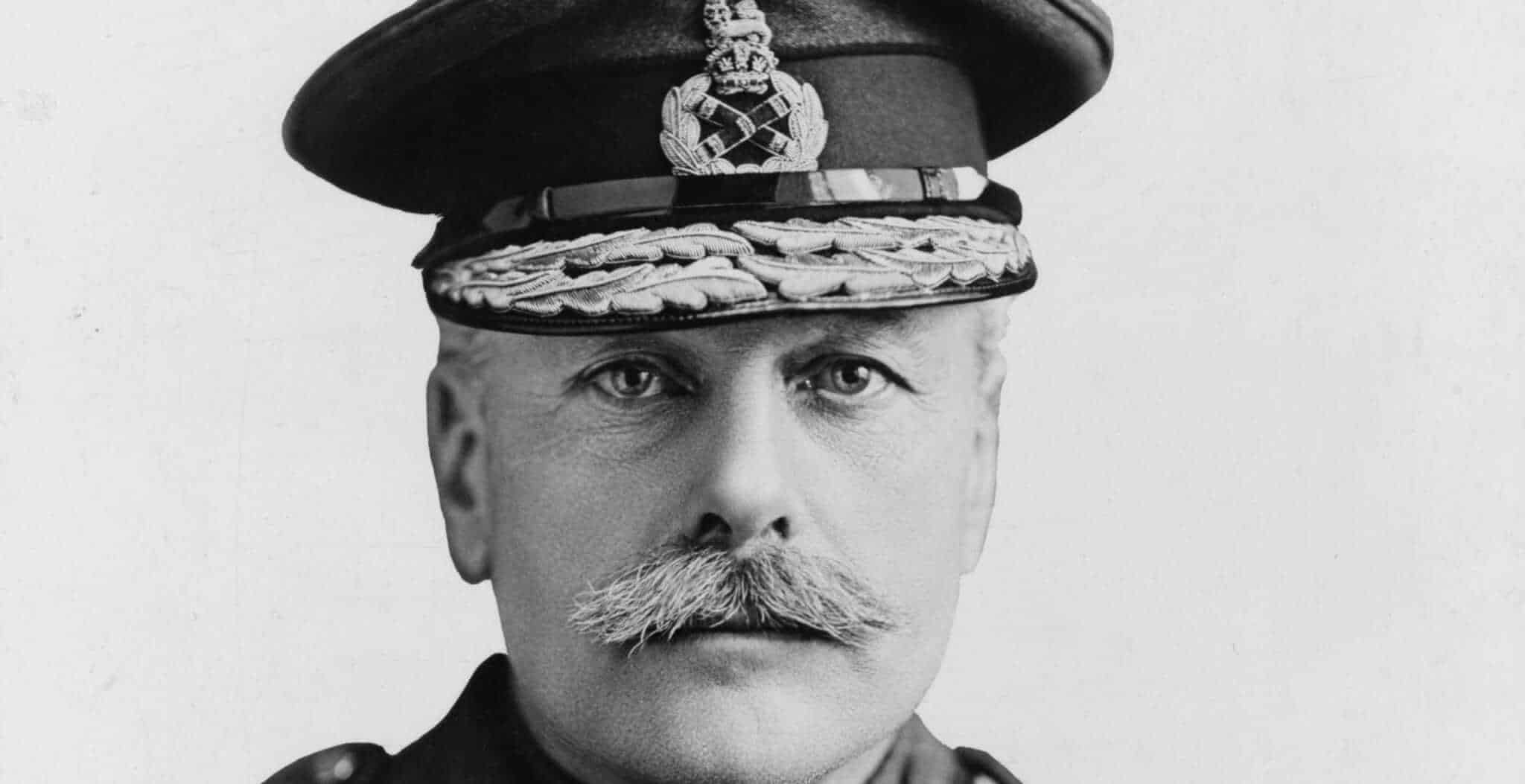

The mystery ships were an undeniably quirky and British response to the Submarine Menace. However, as Rear-Admiral Gordon Campbell wrote in his memoir “My Mystery Ships”: “It must not be imagined that the mystery ships were any invention of the war, as attempts to decoy the enemy are as old as can be. The hoisting of false colours is a long-standing practice, and it is only natural that enterprising officers would go a bit farther and disguise their ships and think of additional ruses.”

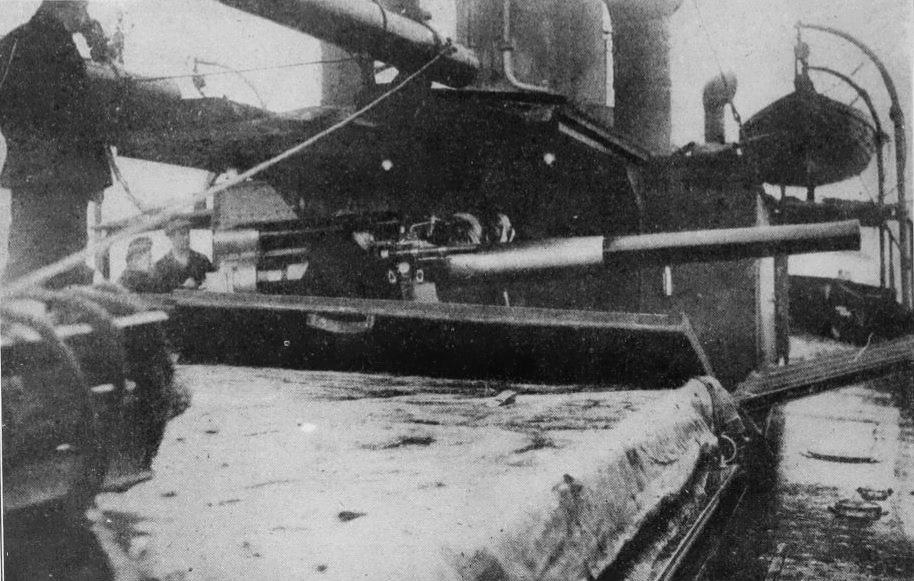

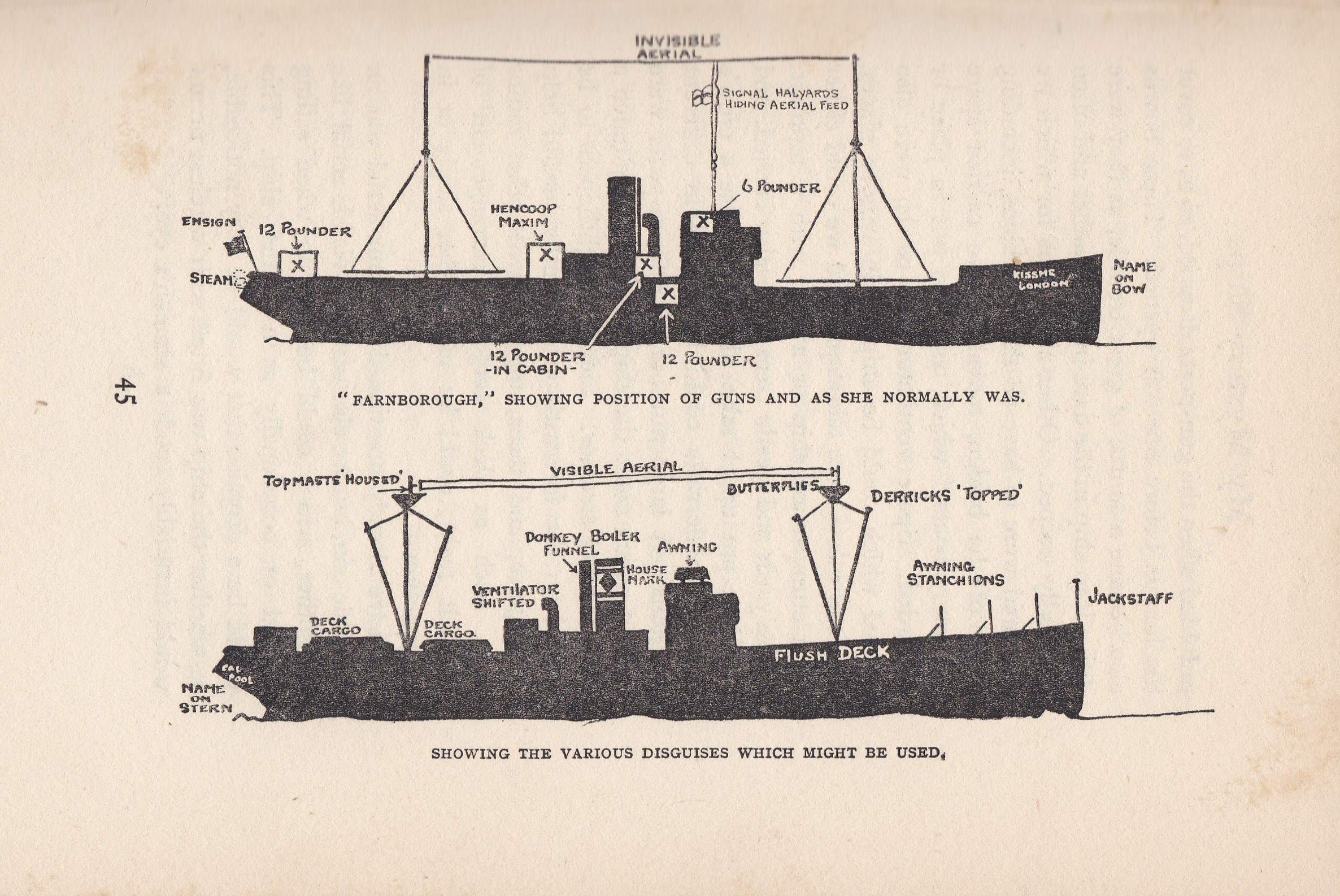

The hoisting of false colours, either of a neutral or allied nation, up until the moment of engagement when the White Ensign was hoisted, was just one of the deceptions that the mystery ships used to decoy enemy submarines. Ships were fitted with false funnels, guns were hidden in hen-coops and deck cargo, and the vessels were given hinged sides that could be quickly dropped to reveal the hefty 12 pounder guns ready to fire on the conning tower when the submarine emerged on the surface.

Submarines were a deadly threat, but they had their own limitations. They carried torpedoes, but these were more certain to hit at relatively short range, since targetted ships could take swift action to avoid them if they spotted the torpedo’s bubble track in the water. Firing torpedoes at short range meant the submarine itself was at risk of damage from the explosion as well as being rammed by the ship. The u-boats’ carrying capacity of torpedoes was limited, so they needed to be used sparingly. Once on the surface, they could man and use their gun, but this made them vulnerable to return fire. They needed to surface, as u-boat commanders required the masters of the vessels they had fired on to hand over their documentation before the ship sank, whenever possible. This would be taken back to the High Command as proof of success and for its intelligence value.

The mystery ships took full advantage of these vulnerabilities to lure the submarines into firstly firing one of their precious torpedoes, than encouraging them to surface by staging fake “panic parties” of men apparently trying to desperately flee the ship. This encouraged the subs to approach the ship at close range. Once the sub’s conning tower and deck presented a sure enough target, all concealment would be abandoned as the mystery ship revealed itself to be a warship in disguise, opening fire and then dropping depth charges as the submarine quickly attempted to submerge again.

It was a task that took nerves of steel and a natural capacity for deception and disguise, as the laconic message sent by Campbell to Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly after the first successful encounter shows:

“’From Farnborough, 6.40. Hull of submarine seen. Position, latitude 57° 56’ 30” N.; longitude 10° 53’ 45” W.

“7.5. Ship being fired at by submarine.

“7.45. Have sunk enemy submarine.

“8.10. Shall I return to report or look for another?”

It was not just a case of adopting disguise at sea. The crews, led by professional naval officers, but consisting of men from many different backgrounds, had to live the parts they were playing. When they left one port, their ship would have one name and identity; on its arrival in another port after operations, it might look entirely different and be under a different name and flag. So effective were the disguises that some of Campbell’s fellow R.N. officers didn’t recognise him behind his bearded, scruffy persona as master of a collier or timber ship.

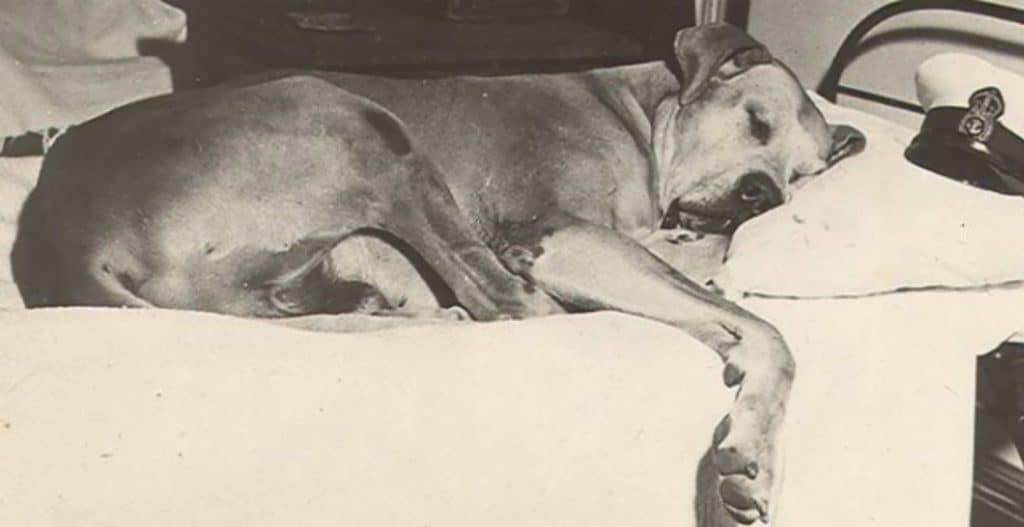

All kinds of ships, including liners, were used as mystery ships. In the case of passenger-carrying ships, some of the decoy crews dressed as women – but only from the waist up, to create the right impression as viewed over the side of the ship through a periscope. When Campbell’s “panic parties” took to the boats, they carried with them a stuffed parrot in a cage, all to add to the authenticity of a merchant crew abandoning ship in a panic and taking their mascot with them.

While in the dockyards, the mystery ships were known under various names, from decoy ships, which gave the game away somewhat, to “Q-ships”, or “S.S. (name)” ships. The “S.S.” in this case stood for “Special Service (Vessel)”. The “Q”, it’s suggested, was because they were operating from Queenstown, now Cobh, in Ireland. They were wide-ranging while on service, changing identity as they moved in search of enemy submarines. Campbell writes: “Before reaching Bermuda, we had ceased to be the Farnborough or Q.5, and again become Loderer. We did this because Loderer was in the Lloyd’s Register Book and Farnborough was not.” Later in the war, the mystery ships adopted the use of torpedoes themselves, adding an extra element of surprise to the disguise.

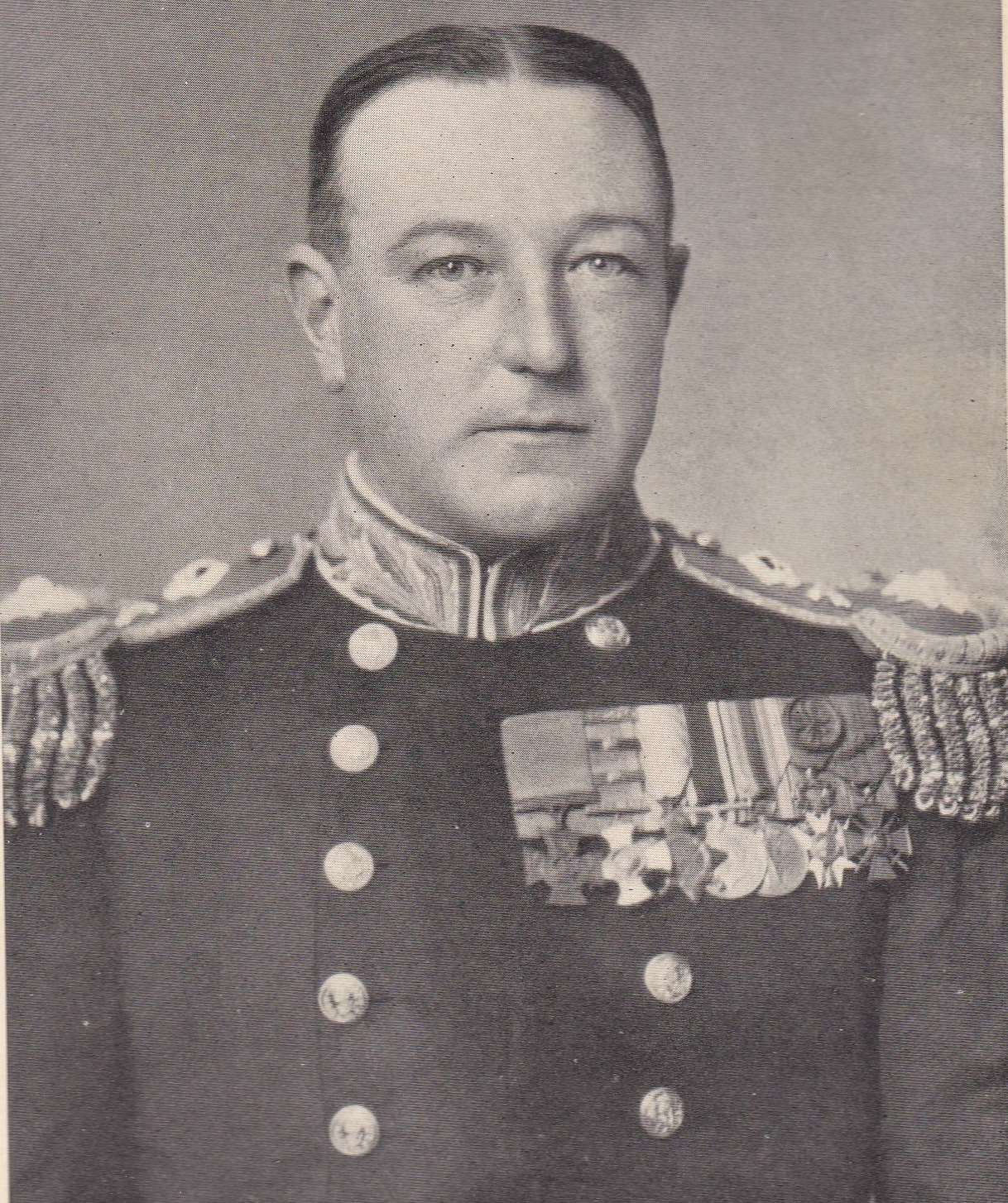

Decoy ships were attacked and sunk by submarines. It happened to Campbell and also to Lieutenant Harold Auten, captain of the Stock Force, which incident was the inspiration for an early silent film. Both Campbell and Auten were recipients of the Victoria Cross.

The story of the mystery ships offers a unique insight into the ingenious ways Britain counteracted the use of submarines in warfare as soon as they came into operation. It is also in its way a classic tale of seafaring, one that rightfully takes its place within the long history of sea-stories as part of the heritage of the British Isles.

Miriam Bibby BA MPhil FSA Scot is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant. She is currently completing her PhD at the University of Glasgow.