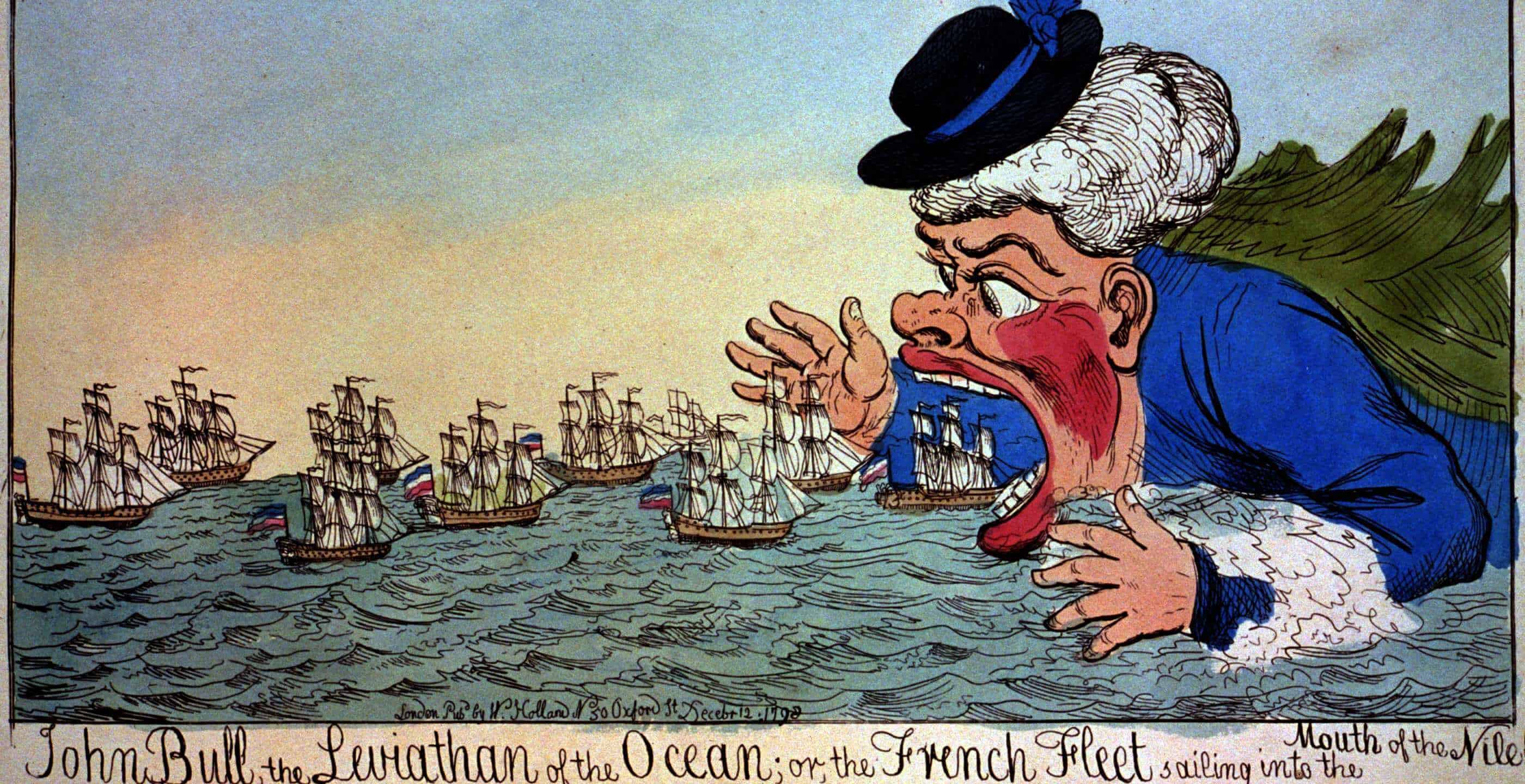

The period 1700 – mid 1800 was marked by British naval dominance, as evidenced by the expansive colonial empire and victories in the War of Spanish Succession and Napoleonic Wars. These triumphs were typically credited to the men since the navy was seen as a man’s world. But such an account overlooks the contributions of the hundreds of women who sailed alongside their husbands into battle, as well as the thousands more who stayed ashore, holding the home together so seamen could take to the sea.

It was customary for wives of warrant officers to go to sea. Occasionally, petty officers and other experienced seamen also brought their wives. These women embraced the demanding life of the sea, not out of a thirst for adventure, but out of loyalty and devotion to their partners. The Admiralty Orders of 1731 forbade the entry of wives, but since captains had the final say on their ships, they often permitted wives to join their crew.

This acceptance was driven by their usefulness on the board. Initially, these women were expected to stay out of the sailors’ way and act as acute observers. Gradually, they began to take on tasks such as washing clothes and sewing. Conflicts did arise due to women’s unfamiliarity with the practice of using saltwater for laundry, leading to complaints in 1796 and 1799.

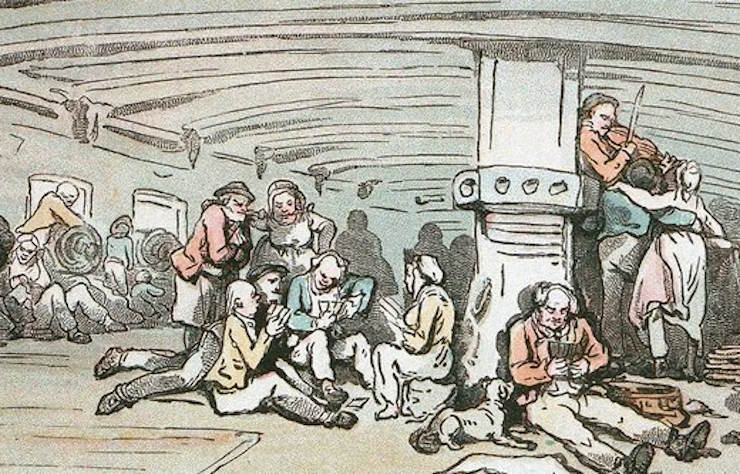

But most captains overlooked these issues, recognizing the value these women brought in preserving discipline and morale. They helped in preventing desertion by providing essential emotional and practical support. In 1789, John Nicol argued how wives were a stabilizing force in the ship because of their ability to listen to seamen’s stories and partake in social activities on board, such that sailors’ morale was uplifted.

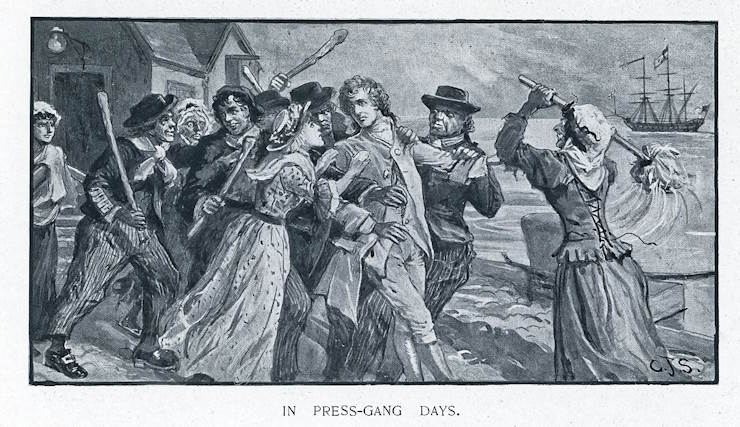

In times of crisis and battle, their utility became even more evident. The navy’s constant need for manpower, as demonstrated by impressment practices, meant that wives who joined their husbands eased the burden by handling menial tasks such as laundering, and sometimes even more critical work. For example, after William Henry Dillon’s ship Horatio struck a rock in 1815, the quick actions of the wives aboard in thrumming the sail kept the ship afloat.

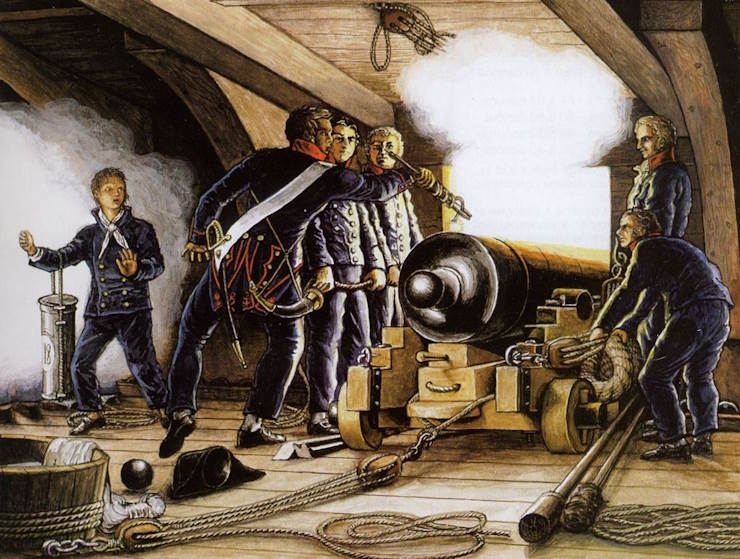

During battles, they performed further dangerous tasks, such as carrying gunpowder from the magazine in the lower deck to the guns at the top. This task involved navigating slippery decks with cartridges of gunpowder while manoeuvring through the chaos of battle. While handling the gunpowder, they also supplied water and wine to the crew, showcasing their resilience and strength.

In certain cases, wives were officially mustered, victualled and paid, a tradition started in the late 17th century when women were hired to serve as nurses or assistants to surgeons on board. And to allay the fear that women could seduce the seamen, it was suggested they were to be seamen’s wives. Some captains opposed having female nurses, arguing that it would cause disruptions, while others recognised their unique nurturing qualities.

By the 1740s, women were frequently employed as assistants, such as the seven wives mustered on the Apollo during the Seven Years’ War in 1747. They were meticulous in caring for the wounded and worked diligently, even after their husbands died in battle. For instance, despite losing their husbands in the Battle of the Nile, Sarah Bates, Mary French, Ann Taylor, and Elizabeth Moore continued working in the surgeon’s grim quarters on Goliath, described by soldiers as a “horrid scene of misery.

Their support may have been limited when serving at sea, but support also came from thousands more wives who never left dry land. These women ensured stability in households and maintained the family, allowing the husbands to remain focused on their naval duties. Their work cannot be underestimated because as the navy expanded, more married men or those in long-term relationships were recruited, resulting in prolonged periods of separation, which added strain on these women and the sailors.

Their primary responsibility was managing household finances. After the 1758 Navy Act, wives received a part of seamen’s pay through remittances, but this often involved travelling considerable distances to collect it from select offices. Since not all seamen could send remittances, many wives relied on poor relief through the local parishes, but it was often insufficient, with parishes unable to support all the poor. So, many wives sought unskilled labour, such as harvesting, cleaning, or selling common wares, and in the worst cases, some turned to prostitution to support their families. This is why in 1799, Mary Ann Radcliffe argued that men should avoid work that might result in women becoming destitute, reducing the risk of prostitution.

Husbands often sent letters containing instructions on managing finances and making reasonable investments to avoid such hardships. High-ranking officials, in particular, directed their wives on how to manage the estate back home. These women were responsible for making decisions about daily household consumption and managing of resources at home. For example, in 1748, Admiral Boscawen’s wife, Frances, meticulously kept household accounts, managed wages, conducted stock-taking, and even recorded revenue from home produce. Her management of property was crucial for maintaining their social status, so she had to ensure everything ran smoothly in her husband’s absence.

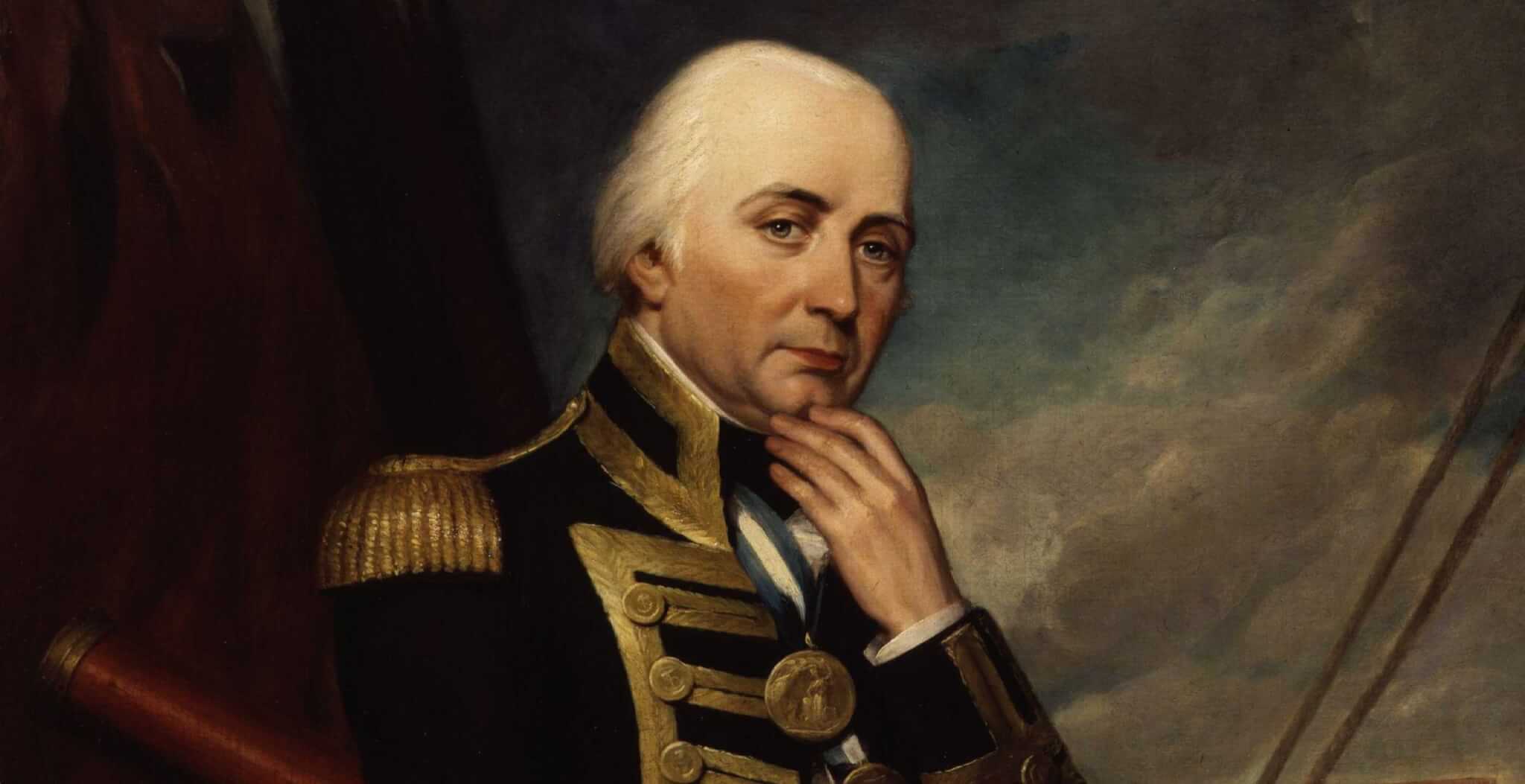

These letters also helped maintain the morale of seamen. They kept husbands informed about family and national affairs, offering a vital connection to life onshore. For instance, during the French Wars from 1793 to 1810 Admiral Collingwood often asked his wife to keep him informed about their family and life in Newcastle.

Many letters expressed concerns about children’s welfare, with seamen giving specific instructions on their upbringing and education. Captain Thomas Wells, for example, asked his wife to ensure their daughter avoided picking up a provincial dialect after she learned to speak.

In addition to letters, wives often sent provisions to their husbands. Officers relied on their wives to send special local foods and clothing. For example, in 1809, Jane Codrington sent hampers of local produce to her husband Edward. Although he appreciated it, he once complained about the spoilage of perishable goods.

Similarly in 1803, Nelson’s mistress, Emma Hamilton supplied him with items such as clothing, and butter. Although the wives of common seamen could not afford such luxuries, they found other ways to support their husbands, such as in 1766 they formulated a cheap method for making waterproof coats for sailors exposed to rainy weather.”

Throughout this period, naval wives — both at sea and onshore — played a crucial role in supporting British maritime dominance. Onboard, these women performed essential tasks during battles and daily ship life, while those onshore ensured households remained stable, enabling men to focus on their naval duties. Their contributions were indispensable, helping the Admiralty maintain a ready and reliable force at sea, while also strengthening the bonds between family, community, and British naval identity. Though often overlooked, their efforts were integral to the continued success of the Royal British Navy.

Priyankush Adhikary is a history graduate from the University of Exeter who has a keen interest in maritime history and African-American history.

Published: 7th November 2024