“If women don’t count, neither shall they be counted”. This was the rallying call for suffragettes on the night of the 1911 census in the UK.

As part of her campaign for universal suffrage, Emmeline Pankhurst called on women to boycott the census to protest against the Liberal Government‘s reluctance to give women the vote. She urged passive protest whereby women who were at home on census night should refuse to complete the return (and risk a £5 fine or a month’s imprisonment), or they should avoid the census altogether by making sure they were out of the house.

On 2nd April 1911, enumerators were sent out to collect the details of all households across the country. The householder was asked to list everyone in the house, so the first form of passive protest for women was to spoil the census form by either refusing to provide any information or by scribbling comments and slogans on it along the lines of ‘I don’t count so I won’t be counted’, ‘I am a woman and women do not count in the state’ or ‘No vote – No census’.

For example, Miss Davies, a suffragette in Birkenhead, completed her census form by giving the name of a male servant and then adding “no other persons, but many women”. Dorothy Bowker wrote: “Dumb Politically, Blind to the Census, Deaf to the Enumerator.” Miss Mary Howey of Hertfordshire scrawled a large ‘Votes for Woman’ slogan on her form, listed her occupation as ‘artist and suffragette ‘ and her infirmity as ‘not enfranchised’.

The second method of passive protest was to avoid being at home that night and therefore avoid being included on the census. Women hid or kept moving from place to place throughout the night to avoid being recorded. One woman apparently spent the night in a cycle shed behind her house, wrapped up in her fur coat to keep warm.

In London, some gathered for a midnight picnic on Wimbledon Common with banners proclaiming “If women don’t count, neither shall they be counted”. Others went to Trafalgar Square where they spent the night talking and singing.

Overnight protests were held all in towns and cities around the country, in places such as Bristol, Ipswich, Reading, Cardiff, Liverpool, Edinburgh and Manchester, where a house packed with census evaders became known as “Census Lodge”.

Punch joked: “The suffragettes have definitely taken leave of their census.”

Emily Davison, who would tragically lose her life at the Derby two years later, hid in a broom cupboard in the Houses of Parliament for 46 hours so that she could record the Palace of Westminster as her place of residence. Discovered by a cleaner, she was arrested and then released without charge.

Emily was duly recorded in the 1911 Census with her address being given as ‘found hiding in the Crypt of Westminster Hall, Westminster’. Ironically however, Emily’s landlady at her rented home in Coram Street also included her on the census form, and so she was actually recorded twice!

Later a plaque in her memory was placed in the broom cupboard by Tony Benn, Helena Kennedy QC and Jeremy Corbyn MP, former leader of the Labour Party, stating ‘…a modest reminder of a great woman with a great cause who never lived to see it prosper but played a significant part in making it possible’.

After the census protests, Emmeline Pankhurst replied to the negative press coverage the women received with a letter, in which she wrote: ‘The Census is a numbering of the people. Until women count as people for the purpose of representation in the councils of the nation, we shall refuse to be numbered.’

But was the boycott successful in disrupting the census? Despite their efforts to the contrary, many of the protesting women were actually recorded and so the impact of the boycott could be seen as negligible.

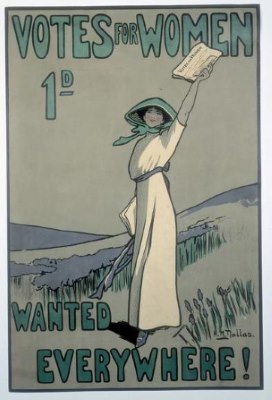

However, whilst it didn’t nullify the census results, it did focus the public’s attention on the suffragette movement and its campaign for ‘Votes for Women’.

Eventually, after the First World War, Parliament passed the 1918 Qualification of Women Act which enfranchised those women over the age of 30 who were either householders or married to a householder, or who held a university degree. It was not until the 1928 Representation of the People Act that women were granted the right to vote on the same terms as men.

Published: 22nd February 2015.