Mention Dunkirk to most British people and images spring to mind of queues of men on beaches awaiting evacuation, little ships bravely crossing the Channel and naval officers brilliantly marshalling their limited resources to bring home over 338,000 men from northern France in May and early June 1940.

There are many other stories about those desperate weeks as the Germans swept across Holland, Belgium and France that are less frequently told, if at all. One is of the nurses on the hospital ships that brought thousands of wounded servicemen back to the safety of England.

In the National Archives in Kew there is a remarkable set of letters written by some of those nurses in the immediate aftermath of the evacuation of France. They represent a testament to their dedication, sense of duty and courage.

These brave women sailed back and forth across the English Channel many times, enduring bombs, mines and attacks by the Luftwaffe, rarely stopping to think about the danger they were in but all the time caring for the wounded men entrusted to their care.

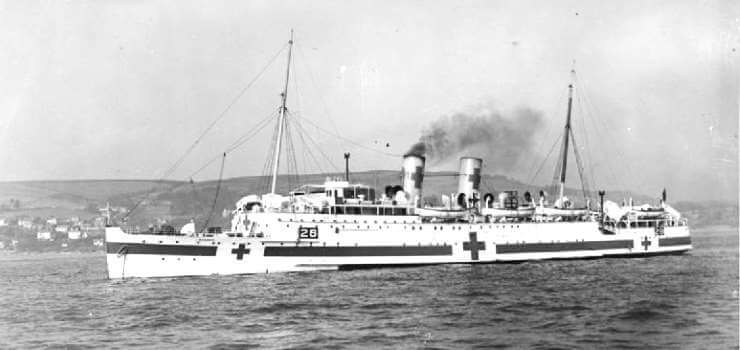

Hospital ships were distinctive, usually painted white and displaying large red crosses but that did not make them immune from attack, as Sister Dora Grayson in charge of the Queen Alexandra’s nurses on the Hospital Carrier (HC) Isle of Guernsey recalled:

“To Dunkirk…the German plane returned and dived backwards and forwards dropping (they said) 10 salvoes of 3 bombs each & machine-gunning all the time. One cannonball went straight through the foremast at the level of the Bridge, which proved that the pilot must have been low enough to see all 5 large Red Crosses…Just as all had given up all hope of survival, an RAF plane came and drove off the Germans”.

Dunkirk was ablaze as the Isle of Guernsey docked after waiting outside the wreck-strewn harbour for four hours, before loading over 600 wounded men on a ship with space for 203 cot cases. Most were passed over the side of the ship as no gangplanks could used on the badly damaged quay. This was Sister Grayson’s fifth voyage in just two weeks, having already evacuated patients from Cherbourg, Boulogne and Dunkirk.

Just two days later, on 2nd June, another hospital ship, the Paris, making its sixth trip to Dunkirk, was bombed by Stukas and sunk. The lifeboat carrying the nurses was subsequently bombed again with several sustaining bad injuries. The previous month the Brighton and the Maid of Kent had both been bombed and sunk at Dieppe, the latter with the loss of 28 crew and medical personnel.

The nurses knew the dangers and yet did not falter from their duty to care for their patients.

These brave women had a magnificent way of understating the stress they were under, captured in the account by the Matron-in-Charge of the Dinard:

“The Captain and Chief Engineer were extremely helpful. They told us afterwards of their great admiration for the way the sisters & I carried on just as if nothing was happening. Some of the young orderlies were very white faced, & no wonder, but all worked splendidly”.

The Dinard was another ship that made multiple trips to France, several of them in the weeks after Dunkirk fell, as another 220,000 troops and civilians were evacuated from the Brittany and Biscay ports before France finally collapsed and surrendered at the end of June. This is the much less well-known Operation Aerial, a story poorly told in the history books.

One of those trips made by the Dinard was to Cherbourg on 16 June – two weeks after the Dunkirk evacuations finished – and one laced with danger as Matron E Thomlinson recounted:

“It was a very changed Cherbourg from our previous visit, with bombs dropping, the continual droning of planes and fires burning. We got our patients safely across, arriving at Southampton at 9.45pm”.

By the next morning, having worked all night to clean the cabins and medical facilities, they were on their way back across the Channel.

“We returned to Cherbourg and found the quay laden with lorries, motor cycles and equipment of every kind. Every effort was being made to save and get away everything possible as we were about to leave. The forts were already blown up and the Germans were very close”.

They hastily loaded their casualties, including some wounded civilians, and sailed overnight to Portland. That was not the end of the danger for the nurses on the Dinard.

“At breakfast time a bomb was dropped on a Naval Auxilliary beside us, which set her on fire. There was a number of casualties, most of which were taken to the Naval Hospital. Several [Hospital] Carriers were anchored there at the time, and all the medical staff and most of the sisters were taken off in boats to go to give assistance. They were away at the hospital all day. We took about 70 of the slighter cases and landed them at Plymouth”.

The captain’s admiration for Matron Thomlinson and her nurses moved him to write to the Matron-in-Chief of the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service at the War Office in London. Captain John Ailwyn Jones’ letter is also preserved in the National Archives

“I feel as Captain of this ship, and now I have a few moments to spare, that I should like to give expression to my admiration and deep regard for the Nursing sisters of this ship.”

“We have recently made two trips to Dunkirk and two to Cherbourg, in each case being the last Hospital Ship to enter and leave the ports. Our second trip to Dunkirk was under extremely severe conditions, bombs and shells dropping all about us and men being wounded and killed alongside our ship on the pier. We had numerous narrow escapes and nerve racking experiences.”

“During all of this our Nurses were really splendid; never a sign of excitement nor panic of any kind; they just carried on, under the able leadership of our Matron calmly and efficiently, and I feel quite sure that their magnificent behavior was an important factor in steadying up the members of the RAMC [Royal Army Medical Corps] personnel with whom they worked.”

“My sentiments are warmly endorsed by every member of the crew of this ship”.

Many of the nurses received Royal Red Cross medals for their part in the evacuations, as did their colleagues working on the hospital trains in the field hospitals in those desperate, chaotic weeks in May and June 1940.

David Worsfold is currently researching the story of Operation Aerial and the post-Dunkirk evacuations – you can read more about this project at https://worsfoldmedia.co.uk/journalism/publications/operation-aerial/