“There were opium dens where one could buy oblivion, dens of horror where the memory of old sins could be destroyed by the madness of sins that were new.” Oscar Wilde in his novel, ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray’ (1891).

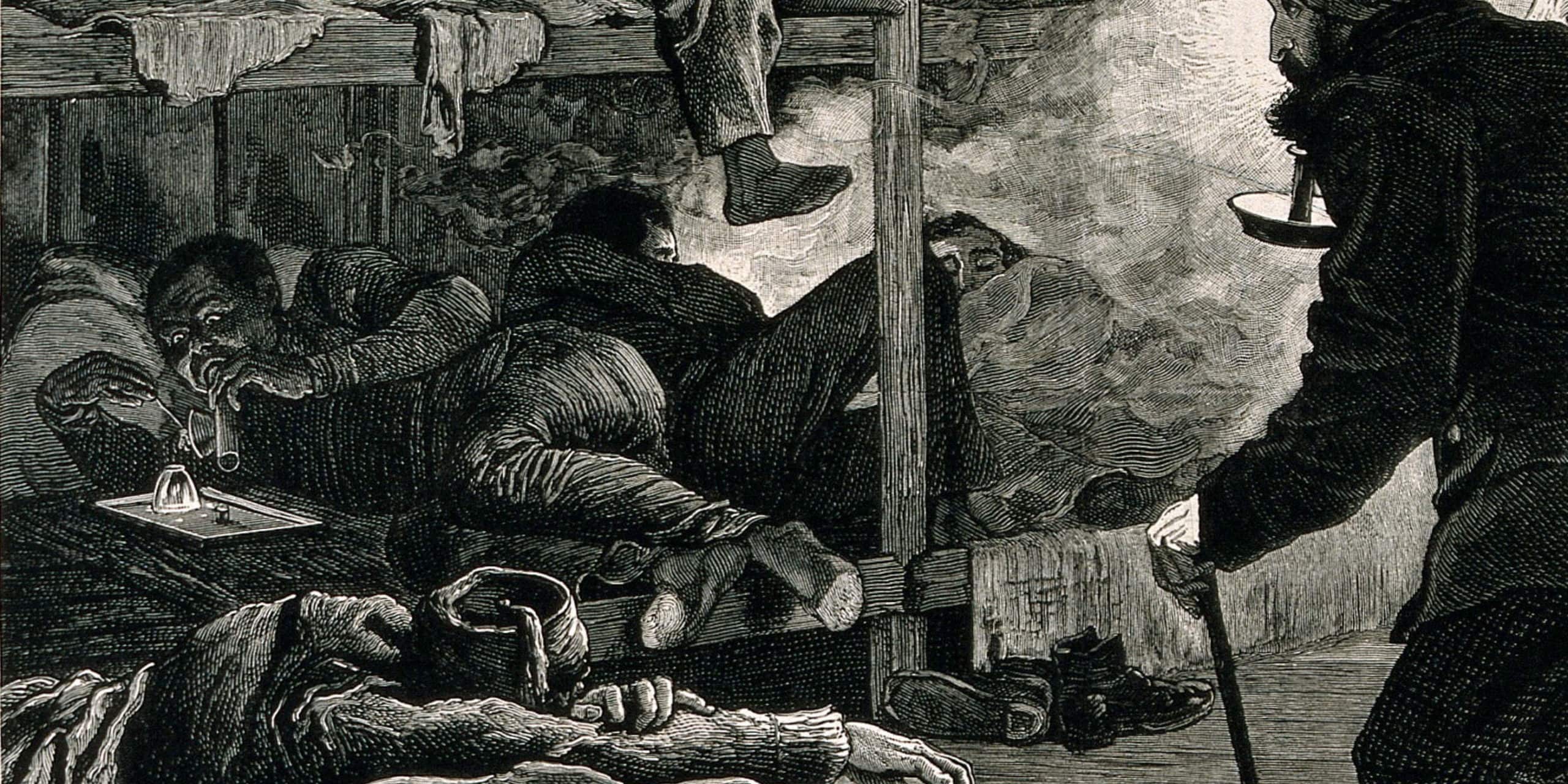

The opium den with all its mystery, danger and intrigue appeared in many Victorian novels, poems and contemporary newspapers, and fuelled the public’s imagination.

“It is a wretched hole… so low that we are unable to stand upright. Lying pell-mell on a mattress placed on the ground are Chinamen, Lascars, and a few English blackguards who have imbibed a taste for opium.” So reported the French journal ‘Figaro’, describing an opium den in Whitechapel in 1868.

The public must have shuddered at these descriptions and imagined areas such as London’s docklands and the East End to be opium-drenched, exotic and dangerous places. In the 1800s a small Chinese community had settled in the established slum of Limehouse in London’s docklands, an area of backstreet pubs, brothels and opium dens. These dens catered mainly for seamen who had become addicted to the drug when overseas.

Despite the lurid accounts of opium dens in the press and fiction, in reality there were few outside of London and the ports, where opium was landed alongside other cargo from all over the British Empire.

The India-China opium trade was very important to the British economy. Britain had fought two wars in the mid 19th century known as the ‘Opium Wars’, ostensibly in support of free trade against Chinese restrictions but in reality because of the immense profits to be made in the trading of opium. Since the British captured Calcutta in 1756, the cultivation of poppies for opium had been actively encouraged by the British and the trade formed an important part of India’s (and the East India Company’s) economy.

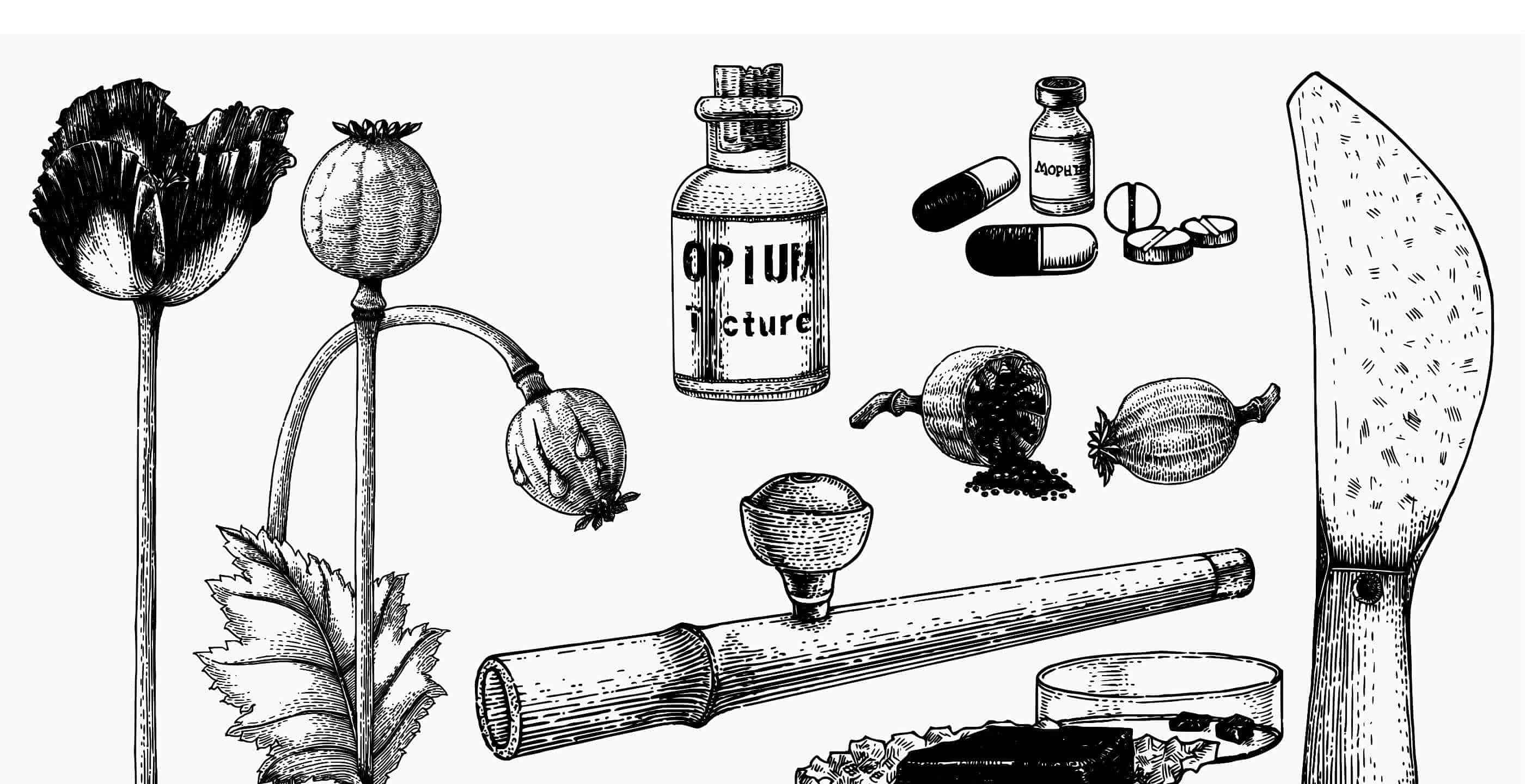

Opium and other narcotic drugs played an important part in Victorian life. Shocking though it might be to us in the 21st century, in Victorian times it was possible to walk into a chemist and buy, without prescription, laudanum, cocaine and even arsenic. Opium preparations were sold freely in towns and country markets, indeed the consumption of opium was just as popular in the country as it was in urban areas.

The most popular preparation was laudanum, an alcoholic herbal mixture containing 10% opium. Called the ‘aspirin of the nineteenth century,’ laudanum was a popular painkiller and relaxant, recommended for all sorts of ailments including coughs, rheumatism, ‘women’s troubles’ and also, perhaps most disturbingly, as a soporific for babies and young children. And as twenty or twenty-five drops of laudanum could be bought for just a penny, it was also affordable.

19th century recipe for a cough mixture:

Two tablespoonfuls of vinegar,

Two tablespoonfuls of treacle

60 drops of laudanum.

One teaspoonful to be taken night and morning.

Laudanum addicts would enjoy highs of euphoria followed by deep lows of depression, along with slurred speech and restlessness. Withdrawal symptoms included aches and cramps, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea but even so, it was not until the early 20th century that it was recognised as addictive.

Many notable Victorians are known to have used laudanum as a painkiller. Authors, poets and writers such as Charles Dickens, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Elizabeth Gaskell and George Eliot were users of laudanum. Anne Bronte is thought to have modelled the character of Lord Lowborough in ‘The Tenant of Wildfell Hall’ on her brother Branwell, a laudanum addict. The poet Percy Bysshe Shelley suffered terrible laudanum-induced hallucinations. Robert Clive, ‘Clive of India’, used laudanum to ease gallstone pain and depression.

Many of the opium-based preparations were targeted at women. Marketed as ‘women’s friends’, these were widely prescribed by doctors for problems with menstruation and childbirth, and even for fashionable female maladies of the day such as ‘the vapours’, which included hysteria, depression and fainting fits.

Children were also given opiates. To keep them quiet, children were often spoon fed Godfrey’s Cordial (also called Mother’s Friend), consisting of opium, water and treacle and recommended for colic, hiccups and coughs. Overuse of this dangerous concoction is known to have resulted in the severe illness or death of many infants and children.

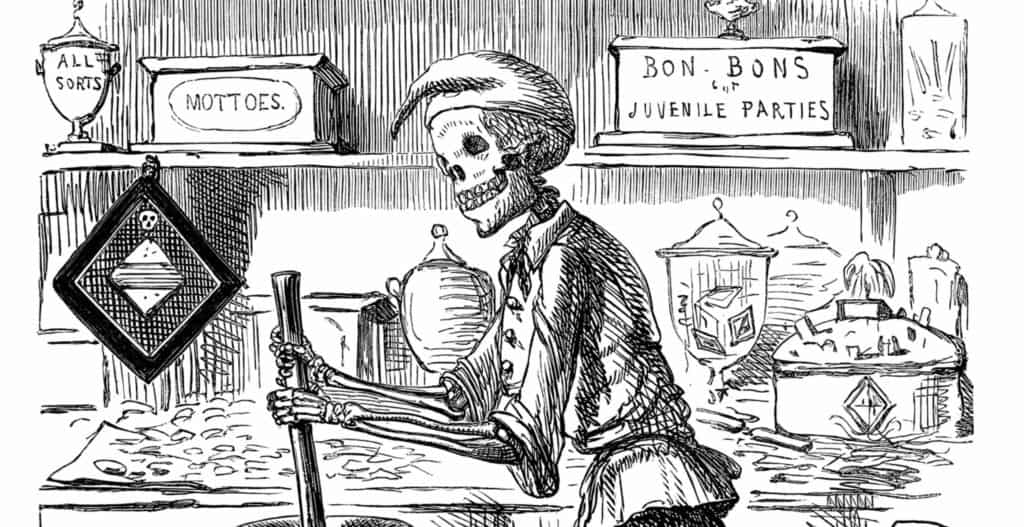

The 1868 Pharmacy Act attempted to control the sale and supply of opium-based preparations by ensuring that they could only be sold by registered chemists. However this was largely ineffective, as there was no limit on the amount the chemist could sell to the public.

The Victorian attitude to opium was complex. The middle and upper classes saw the heavy use of laudanum among the lower classes as ‘misuse’ of the drug; however their own use of opiates was seen as no more than a ‘habit’.

The end of the 19th century saw the introduction of a new pain reliever, aspirin. By this time many doctors were becoming concerned about the indiscriminate use of laudanum and its addictive qualities.

There was now a growing anti-opium movement. The public viewed the smoking of opium for pleasure as a vice practised by Orientals, an attitude fuelled by sensationalist journalism and works of fiction such as Sax Rohmer’s novels. These books featured the evil arch villain Dr Fu Manchu, an Oriental mastermind determined to take over the Western world.

In 1888 Benjamin Broomhall formed the “Christian Union for the Severance of the British Empire with the Opium Traffic”. The anti-opium movement finally won a significant victory in 1910 when after much lobbying, Britain agreed to dismantle the India-China opium trade.

Published: 26th January 2015.